React Fundamentals

<– back to React Nanodegree homepage

1. Why React

1.1 Introduction

Before we actually dive into the syntax of React, let’s take a step back and talk about what makes React special.

- It’s compositional model

- It’s declarative nature

- The way data flows through a Component

- That React is really just JavaScript

1.2 What is Composition

Benefits of Composition

Because the concept of composition is such a large part of what makes React awesome and incredible to work with, let’s dig into it a little bit. Remember that composition is just combining simple functions together to create complex functions. There are a couple of key ingredients here that we don’t want to lose track of. These ingredients are:

- simple functions

- combined to create another function

Composition is built from simple functions. Let’s look at an example:

function getProfileLink (username) {

return 'https://github.com/' + username

}

This function is ridiculously simple, isn’t it? It’s just one line! Similarly, the getProfilePic function is also just a single line:

function getProfilePic (username) {

return 'https://github.com/' + username + '.png?size=200'

}

These are definitely simple functions, so to compose them, we’d just combine them together inside another function:

function getProfileData (username) {

return {

pic: getProfilePic(username),

link: getProfileLink(username)

}

}

Now we could have written getProfileData without composition by providing the data directly:

function getProfileData (username) {

return {

pic: 'https://github.com/' + username + '.png?size=200',

link: 'https://github.com/' + username

}

}

There’s nothing technically wrong with this at all; this is entirely accurate JavaScript code. But this isn’t composition. There are also a couple of potential issues with this version which isn’t using composition. If the user’s link to GitHub is needed somewhere else, then duplicate code would be needed. A good function should follow the “DOT” rule:

Do One Thing

This function is doing a couple of different (however minor) things; it’s creating two different URLs, storing them as properties on an object, and then returning that object. In the composed version, each function just does one thing:

getProfileLink– just builds up a string of the user’s GitHub profile linkgetProfilePic– just builds up a string the user’s GitHub profile picturegetProfileData– returns a new object

React & Composition

React makes use of the power of composition, heavily! React builds up pieces of a UI using components. Let’s take a look at some pseudo code for an example. Here are three different components:

<Page />

<Article />

<Sidebar />

Now let’s take these simple components, combine them together, and create a more complex component (aka, composition in action!):

<Page>

<Article />

<Sidebar />

</Page>

Now the Page component has the Article and Sidebar components inside. This is just like the earlier example where getProfileData had getProfileLink and getProfilePic inside it.

We’ll dig into components soon, but just know that composition plays a huge part in building React components.

Composition Recap

Composition occurs when simple functions are combined together to create more complex functions. Think of each function as a single building block that does one thing (DOT). When you combine these simple functions together to form a more complex function, this is composition.

Further Research

- Compose me That: Function Composition in JavaScript

- Functional JavaScript: Function Composition For Every Day Use

1.3 Declarative Code

Imperative Code

A lot of JavaScript is imperative code. If you don’t know what “imperative” means here, then you might be scratching your head a bit. According to the dictionary, “imperative” means:

expressing a command; commanding

When JavaScript code is written imperatively, we tell JavaScript how we want something done. Think of it as if we’re giving JavaScript commands on exactly what steps it should take. For example, I give you the humble for loop:

const people = ['Amanda', 'Farrin', 'Geoff', 'Karen', 'Richard', 'Tyler']

const excitedPeople = []

for (let i = 0; i < people.length; i++) {

excitedPeople[i] = people[i] + '!'

}

If you’ve worked with JavaScript any length of time, then this should be pretty straightforward. We’re looping through each item in the people array, adding an exclamation mark to their name, and storing the new string in the excitedPeople array. Pretty simple, right?

This is imperative code, though. We’re commanding JavaScript what to do at every single step. We have to give it commands to:

- set an initial value for the iterator - (

let i = 0) - tell the

forloop when it needs to stop - (i < people.length) - get the person at the current position and add an exclamation mark - (

people[i] + '!') - store the data in the

ith position in the other array - (excitedPeople[i]) - increment the

ivariable by one - (i++)

Remember the example of keeping the air temperature at 71º? In my old car, I would turn the knob to get the cold air flowing. But if it got too cold, then I’d turn the knob up higher. Eventually, it would get too warm, and I’d have to turn the knob down a bit, again. I’d have to manage the temperature myself with every little change. Doesn’t this sound like an imperative situation to you? I have to manually do multiple steps. It’s not ideal, so let’s improve things!

Declarative Code

In contrast to imperative code, we’ve got declarative code. With declarative code, we don’t code up all of the steps to get us to the end result. Instead, we declare what we want done, and JavaScript will take care of doing it. We tell JavaScript what we want done. This explanation is a bit abstract, so let’s look at an example. Let’s take the imperative for loop code we were just looking at and refactor it to be more declarative.

With the imperative code we were performing all of the steps to get to the end result. What is the end result that we actually want, though? Well, our starting point was just an array of names:

const people = ['Amanda', 'Farrin', 'Geoff', 'Karen', 'Richard', 'Tyler']

The end goal that we want is an array of the same names but where each name ends with an exclamation mark:

["Amanda!", "Farrin!", "Geoff!", "Karen!", "Richard!", "Tyler!"]

To get us from the starting point to the end, we’ll just use JavaScript’s .map() function to declare what we want done.

const excitedPeople = people.map(name => name + '!')

That’s it! Notice that with this code we haven’t:

- created an iterator object

- told the code when it should stop running

- used the iterator to access a specific item in the

peoplearray - stored each new string in the

excitedPeoplearray

…all of those steps are taken care of by JavaScript’s .map() Array method.

.map() and .filter()

A bit rusty on JavaScript’s .map() and .filter() Array methods? Or perhaps they’re brand new to you. In either case, we’ll be diving into them in the React is “just JavaScript” section. Hold tight!

React is Declarative

We’ll get to writing React code very soon, but let’s take another glimpse at it to show how it’s declarative.

<button onClick={activateTeleporter}>Activate Teleporter</button>

It might seem odd, but this is valid React code and should be pretty easy to understand. Notice that there’s just an onClick attribute on the button…we aren’t using .addEventListener() to set up event handling with all of the steps involved to set it up. Instead, we’re just declaring that we want the activateTeleporter function to run when the button is clicked.

Declarative Code Recap

Imperative code instructs JavaScript on how it should perform each step. With declarative code, we tell JavaScript what we want to be done, and let JavaScript take care of performing the steps.

React is declarative because we write the code that we want, and React is in charge of taking our declared code and performing all of the JavaScript/DOM steps to get us to our desired result.

1.3 Further Research

- Tyler’s Imperative vs Declarative Programming blog post

- Difference between declarative and imperative in React.js? from StackOverflow

1.4 Unidirectional Data Flow

Before React, one popular technique for managing state changes in an app over time, was to use data bindings, so that when data changes in one place, those changes are automatically reflected in other places in the app.

Any part of the app that had that data could also change it. But, as the app grows this technique makes it difficult to determine how a change in one place automatically and implicitly affects the rest of the app.

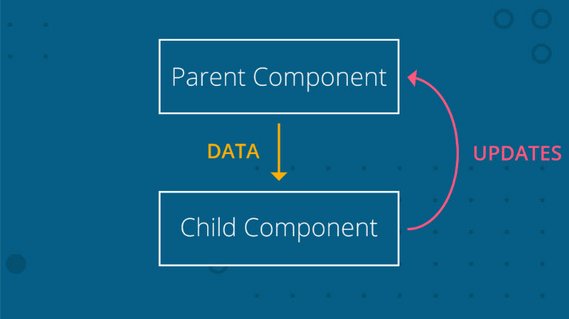

React uses an explicit method for passing data between components that makes it a lot easier to track changes to the state, and how they affect other places of the app.

This is called unidirectional data flow because the data flows one way from parent elements down to children.

Data-Binding In Other Frameworks

Front-end frameworks like Angular and Ember make use of two-way data bindings. In two-way data binding, the data is kept in sync throughout the app no matter where it is updated. If a model changes the data, then the data updates in the view. Alternatively, if the user changes the data in the view, then the data is updated in the model. Two-way data binding sounds really powerful, but it can make the application harder to reason about and know where the data is actually being updated.

1.4 Further Research

React’s Data-flow

Data moves differently with React’s unidirectional data flow. In React, the data flows from the parent component to a child component.

Data flows down from parent component to child component. Data updates are sent to the parent component where the parent performs the actual change.

In the image above, we have two components:

- a parent component

- a child component

The data lives in the parent component and is passed down to the child component. Even though the data lives in the parent component, both the parent and the child components can use the data. However, if the data must be updated, then only the parent component should perform the update. If the child component needs to make a change to the data, then it would send the updated data to the parent component where the change will actually be made. Once the change is made in the parent component, the child component will be passed the data (that has just been updated!).

Now, this might seem like extra work, but having the data flow in one direction and having one place where the data is modified makes it much easier to understand how the application works.

1.4 Quiz

1.4 Question 1 of 2

A FlightPlanner component stores the information for booking a flight. It also contains DatePicker and DestinationPicker as child components. Here’s what the code might look like:

<FlightPlanner>

<DatePicker />

<DestinationPicker />

</FlightPlanner>

If this were a React application, which component should be in charge of making updates to the data? Check all that apply.

FlightPlannerDatePickerDestinationPicker

Now let’s say that the FlightPlanner component has two child components: LocationPicker and DatePicker. LocationPicker itself is a parent component that has two child components: OriginPicker and DestinationPicker.

1.4 Question 2 of 2

If the following sample code were a React application, which of the following components should be in charge of making updates to data? Check all that apply.

<FlightPlanner>

<LocationPicker>

<OriginPicker />

<DestinationPicker />

</LocationPicker>

<DatePicker />

</FlightPlanner>

FlightPlanner- is the parent component and stores all of the flight data, any changes to the data should be made by this component.DatePicker- receives the data from its parentLocationPicker- is a parent component, it would make sense that it would handle all changes for its child components.OriginPicker- receives the data from its parentDestinationPicker- receives the data from its parent

Data Flow in React Recap

In React, data flows in only one direction, from parent to child. If data is shared between sibling child components, then the data should be stored in the parent component and passed to both of the child components that need it.

1.5 React is Just JavaScript

It’s Just JavaScript

One of the great things about React is that a lot of what you’ll be using is regular JavaScript. To make sure you’re ready to move forward, please take a look at the following code:

const shelf1 = [{name: 'name1', shelf: 'a'},{name: 'name2', shelf: 'a'}];

const shelf2 = [{name: 'name3', shelf: 'b'},{name: 'name4', shelf: 'b'}];

const allBooks = [...shelf1, ...shelf2];

const filter = books => shelf => books.filter(b => {

return b.shelf === shelf;

});

const filterBy = filter(allBooks);

const booksOnShelf = filterBy('b');

If any of the code above looks confusing, or if you simply need a refresher on E6, please go through our ES6 course before moving forward.

Here’s a couple links for a quick refresher.

- Udacity ES6 course - Syntax notes - destructuring, spread, & rest operators

- Currying and ES6 Arrow Functions - with double arrow functions

Over the past couple of years, functional programming has had a large impact on the JavaScript ecosystem and community. Functional programming is an advanced topic in JavaScript and fills hundreds of books. It’s too complex to delve into the benefits of functional programming (we’ve got to get to React content, right?!?).

React builds on a lot of the techniques of functional programming…techniques that you’ll learn as you go through this program. However, there are a couple of important JavaScript functions that are vital to functional programming that we should look at. These are the Array’s .map() and .filter() methods.

Array’s .map() Method

If you’re not familiar with JavaScript’s Array .map() method, it gets called on an existing array and returns a new array based on what is returned from the function that’s passed as an argument. Let’s take a look:

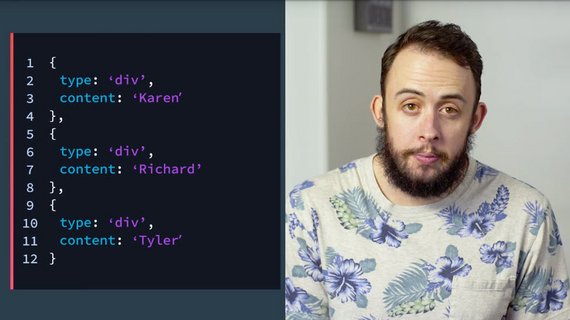

const names = ['Karen', 'Richard', 'Tyler'];

const nameLengths = names.map( name => name.length );

Let’s go over what’s happening here. The .map() method works on arrays, so we have to have an array to start with:

const names = ['Karen', 'Richard', 'Tyler'];

We call .map() on the names array and pass it a function as an argument:

names.map( name => name.length );

The arrow function that’s passed to .map() gets called for each item in the names array! The arrow function receives the first name in the array, stores it in the name variable and returns its length. Then it does that again for the remaining two names.

.map() returns a new array with the values that are returned from the arrow function:

const nameLengths = names.map( name => name.length );

So nameLengths will be a new array [5, 7, 5]. This is important to understand; the .map() method returns a new array, it does not modify the original array.

This was just a brief overview of how the .map() method works. For a deeper dive, check out .map() on MDN.

.map() Quiz

Use the provided music data array and the .map() method to create a new array that contains items in the format:

<album-name> by <artist> sold <sales> copies

Store the new array in an albumSalesStrings array. So the first item in the albumSalesStrings array should be “25 by Adele sold 1731000 copies”

/* Using .map()

*

* Using the musicData array and .map():

* - return a string for each item in the array in the following format

* <album-name> by <artist> sold <sales> copies

* - store the returned data in a new albumSalesStrings variable

*

* Note:

* - do not delete the musicData variable

* - do not alter any of the musicData content

* - do not format the sales number, leave it as a long string of digits

*/

const musicData = [

{ artist: 'Adele', name: '25', sales: 1731000 },

{ artist: 'Drake', name: 'Views', sales: 1608000 },

{ artist: 'Beyonce', name: 'Lemonade', sales: 1554000 },

{ artist: 'Chris Stapleton', name: 'Traveller', sales: 1085000 },

{ artist: 'Pentatonix', name: 'A Pentatonix Christmas', sales: 904000 },

{ artist: 'Original Broadway Cast Recording',

name: 'Hamilton: An American Musical', sales: 820000 },

{ artist: 'Twenty One Pilots', name: 'Blurryface', sales: 738000 },

{ artist: 'Prince', name: 'The Very Best of Prince', sales: 668000 },

{ artist: 'Rihanna', name: 'Anti', sales: 603000 },

{ artist: 'Justin Bieber', name: 'Purpose', sales: 554000 }

];

// SOLUTION

const albumSalesStrings =

musicData.map(obj => `${obj.name} by ${obj.artist} sold ${obj.sales} copies`);

console.log(albumSalesStrings);

Array’s .filter() Method

JavaScript’s Array .filter() method is similar to the .map() method:

- it is called on an array

- it takes a function as an argument

- it returns a new array

The difference is that the function passed to .filter() is used as a test, and only items in the array that pass the test are included in the new array. Let’s take a look at an example:

const names = ['Karen', 'Richard', 'Tyler'];

const shortNames = names.filter( name => name.length < 6 );

Just as before, we have the starting array:

const names = ['Karen', 'Richard', 'Tyler'];

We call .filter() on the names array and pass it a function as an argument:

names.filter( name => name.length < 6 );

Again, just like with .map() the arrow function that’s passed to .filter() gets called for each item in the names array. The first item (i.e. ‘Karen’) is stored in the name variable. Then the test is performed - this is what’s doing the actual filtering. It checks the length of the name. If it’s 6 or greater, then it’s skipped (and not included in the new array!). But if the length of the name is less than 6, then name.length < 6 returns true and the name is included in the new array!

And lastly, just like with .map() the .filter() method returns a new array instead of modifying the original array:

const shortNames = names.filter( name => name.length < 6 );

So shortNames will be the new array ['Karen', 'Tyler']. Notice that it only has two names in it now, because ‘Richard’ is 7 characters and was filtered out.

This was just a brief overview of how the .filter() method works. For a deeper dive, check out .filter() on MDN.

.filter() Quiz

Use the provided music data array and the .filter() method to create a new array that only contains albums with names between 10 and 25 characters long. Store the new array in a variable called results.

/* Using .filter()

*

* Using the musicData array and .filter():

* - return only album objects where the album's name is

* 10 characters long, 25 characters long, or anywhere in between

* - store the returned data in a new `results` variable

*

* Note:

* - do not delete the musicData variable

* - do not alter any of the musicData content

*/

const musicData = [

{ artist: 'Adele', name: '25', sales: 1731000 },

{ artist: 'Drake', name: 'Views', sales: 1608000 },

{ artist: 'Beyonce', name: 'Lemonade', sales: 1554000 },

{ artist: 'Chris Stapleton', name: 'Traveller', sales: 1085000 },

{ artist: 'Pentatonix', name: 'A Pentatonix Christmas', sales: 904000 },

{ artist: 'Original Broadway Cast Recording',

name: 'Hamilton: An American Musical', sales: 820000 },

{ artist: 'Twenty One Pilots', name: 'Blurryface', sales: 738000 },

{ artist: 'Prince', name: 'The Very Best of Prince', sales: 668000 },

{ artist: 'Rihanna', name: 'Anti', sales: 603000 },

{ artist: 'Justin Bieber', name: 'Purpose', sales: 554000 }

];

// SOLUTION

const results =

musicData.filter(album => album.name.length >= 10 && album.name.length <= 25);

console.log(results);

Combining .map() And .filter() Together

What makes .map() and .filter() so powerful is that they can be combined. Because both methods return arrays, we can chain the method calls together so that the returned data from one can be a new array for the next.

const names = ['Karen', 'Richard', 'Tyler'];

const shortNamesLengths =

names.filter( name => name.length < 6 ).map( name => name.length );

To break it down, the names array is filtered, which returns a new array, but then .map() is called on that new array, and returns a new array of its own! This new array that’s returned from .map() is what’s stored in shortNamesLengths.

.filter() First!

On a side note, you’ll want to run things in this order - .filter() first and then .map(). Because .map() runs the function once for each item in the array, it will be faster if the array were already filtered.

.filter() and .map() Quiz

Using the same music data, use .filter() and .map() to filter and map over the list and store the result in a variable named popular. Use .filter() to filter the list down to just the albums that have sold over 1,000,000 copies. Then chain .map() onto the returned array to create a new array that contains items in the format:

<artist> is a great performer

The first item in the popular array will be ‘Adele is a great performer’.

/* Combining .filter() and .map()

*

* Using the musicData array, .filter, and .map():

* - filter the musicData array down to just the albums that have

* sold over 1,000,000 copies

* - on the array returned from .filter(), call .map()

* - use .map() to return a string for each item in the array in the

* following format: "<artist> is a great performer"

* - store the array returned form .map() in a new "popular" variable

*

* Note:

* - do not delete the musicData variable

* - do not alter any of the musicData content

*/

const musicData = [

{ artist: 'Adele', name: '25', sales: 1731000 },

{ artist: 'Drake', name: 'Views', sales: 1608000 },

{ artist: 'Beyonce', name: 'Lemonade', sales: 1554000 },

{ artist: 'Chris Stapleton', name: 'Traveller', sales: 1085000 },

{ artist: 'Pentatonix', name: 'A Pentatonix Christmas', sales: 904000 },

{ artist: 'Original Broadway Cast Recording',

name: 'Hamilton: An American Musical', sales: 820000 },

{ artist: 'Twenty One Pilots', name: 'Blurryface', sales: 738000 },

{ artist: 'Prince', name: 'The Very Best of Prince', sales: 668000 },

{ artist: 'Rihanna', name: 'Anti', sales: 603000 },

{ artist: 'Justin Bieber', name: 'Purpose', sales: 554000 }

];

const popular = musicData

.filter(album => album.sales > 1000000)

.map(album => `${album.artist} is a great performer`);

console.log(popular);

React is Just JavaScript Recap

React builds on what you already know - JavaScript! You don’t have to learn a special template library or a new way of doing things.

Two of the main methods that you’ll be using quite a lot are:

.map().filter()

It’s important that you’re comfortable using these methods, so take some time to practice using them. Why not look through some of your existing code and try converting your for loops to .map() calls or see if you can remove any if statements by using .filter().

1.6 Recap

Let’s recap on some of the things we covered in this lesson on why React is great:

- its compositional model

- its declarative nature

- the way data flows from parent to child

- and that React is really just JavaScript

Lesson Challenge

Read these 3 articles that cover some of the essentials of React:

Answer the following questions (in your own words) and share your answers with your Study Group.

- What is the “Virtual DOM”?

- Explain what makes React performant.

- Explain the Diffing Algorithm to someone who does not have any programming experience.

2. Rendering UI w/ React

2.1 Rendering UI Intro

React uses JavaScript objects to create React elements. We’ll use these React elements to describe what we want the page to look like, and React will be in charge of generating the DOM nodes to achieve the result.

Recall from the previous lesson the difference between imperative and declarative code. The React code that we write is declarative because we aren’t telling React what to do; instead, we’re writing React elements that describe what the page should look like, and React does all of the implementation work to get it done.

Enough theory, let’s get to it and create some elements!

2.2 Elements and JSX

Watch First

We’ll be looking at using React’s .createElement() method in the next couple of videos. For starters, here is its signature:

React.createElement( /* type */, /* props */, /* content */ );

We’ll take a deep dive into what all that entails in just a bit! We’ll start things out with a project that’s already set up. For now, don’t worry about creating a project or coding along. There will be plenty of hands-on work for you to do soon enough!

We’ll start building our in-class project, Contacts App, in the next section. If you would like to code along for the next few videos, you can use this React Sandbox.

💡 Trying Out React Code 💡

React is an extension of JavaScript (i.e., a JavaScript library), but it isn’t built into your browser. You wouldn’t be able to test out React code samples in your browser console the way you would if you were learning JavaScript. In just a bit, we’ll see how to install and use a React environment!

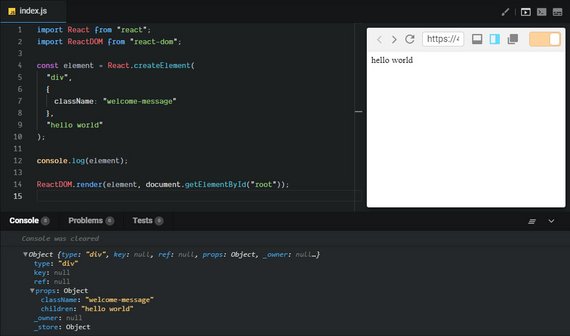

React.createElement

import React from "react";

import ReactDOM from "react-dom";

const element = React.createElement("div", null, "hello world");

ReactDOM.render(element, document.getElementById("root"));

Live Demo: React Element on CodeSandbox

ReactDOM

One thing to keep in mind is that we could be rendering out to different destinations. For that reason, ReactDOM was split out of the React library. Some other destinations include:

- render on the server

- native devices

- VR environments

Rendering Elements onto the DOM

In the previous video, we used ReactDOM’s render() method to render our element onto a particular area of a page. In particular, we rendered the element onto a DOM node called root. But where did this root come from?

Apps built with React typically have a single root DOM node. For example, an HTML file may contain a <div> with the following:

<div id="root"></div>

By passing this DOM node into getElementById(), React will end up controlling the entirety of its contents. Another way to think about this is that this particular <div> will serve as a “hook” for our React app; this is the area where React will take over and render our UI!

2.2 Question 1 of 3

What will myBio hold when the following code is run?

import React from 'react';

const myBio = React.createElement('div', null, 'Hi, I love porcupines.');

- a reference to a DOM node

- a DOM node itself

- a JavaScript object

- a JavaScript class

DOM nodes - className

import React from "react";

import ReactDOM from "react-dom";

const element = React.createElement(

"div",

{

className: "welcome-message"

},

"hello world"

);

console.log(element);

ReactDOM.render(element, document.getElementById("root"));

Live Demo: React Element on CodeSandbox

When we’re creating these React elements we must remember that we are describing DOM nodes not HTML elements. For that reason we must use things like ‘className’ rather than ‘class’ since ‘class’ is a reserved word.

Virtual DOM - objects that describe real DOM nodes

When we call

React.createElementwe haven’t actually created anything in the DOM yet. It’s not until we calrender()that the browser actually creates a real DOM element.

2.2 Question 2 of 3

React allows a lot of HTML attributes to be passed along to the React element. Look through all supported HTML attributes in the React docs and select which of the following attributes are allowed:

- poster

- id

- marginWidth

- for - (‘for’ is a reserved word so instead we can use ‘htmlFor’)

I just used React’s .createElement() method to construct a “React element”. The .createElement() method has the following signature:

React.createElement( /* type */, /* props */, /* content */ );

Let’s break down what each item can be:

-

type– either a string or a React ComponentThis can be a string of any existing HTML element (e.g.

'p','span', or'header') or you could pass a React component (we’ll be creating components with JSX, in just a moment). -

props– eithernullor an objectThis is an object of HTML attributes and custom data about the element.

-

content–null, a string, a React Element, or a React ComponentAnything that you pass here will be the content of the rendered element. This can include plain text, JavaScript code, other React elements, etc.

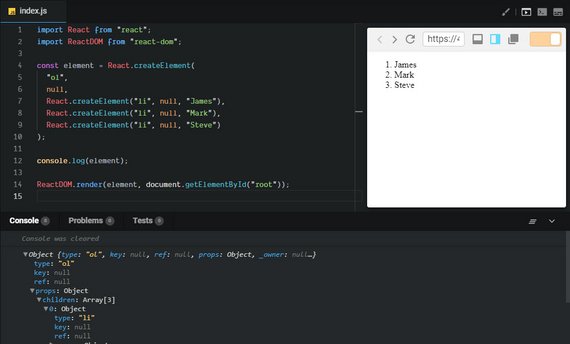

Nested Elements

import React from "react";

import ReactDOM from "react-dom";

const element = React.createElement(

"ol",

null,

React.createElement("li", null, "James"),

React.createElement("li", null, "Mark"),

React.createElement("li", null, "Steve")

);

console.log(element);

ReactDOM.render(element, document.getElementById("root"));

Live Demo: React Element on CodeSandbox

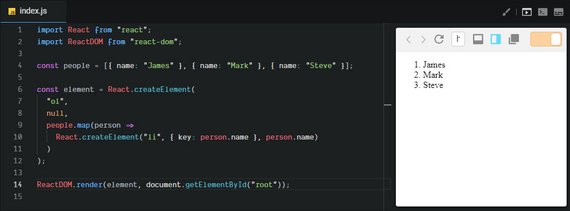

List Data

Now, what we currently have is fine but most of the time when you need a list, you’ll probably have the items in an array somewhere.

Instead of writing out child elements one by one, React lets us provide an array of elements to use as children. This makes it easier to work with existing arrays of data.

So, let’s say we have an array here of people that we want to dynamically generate these list items from this array. We could just map over the people array and for each person, we will generate a list item.

And instead of hard-coding the we will just use person.name to get the same result.

import React from "react";

import ReactDOM from "react-dom";

const people = [

{ name: 'James' },

{ name: 'Mark' },

{ name: 'Steve' }

];

const element = React.createElement(

"ol",

null,

people.map((person) => (

React.createElement('li', null, person.name)

))

);

ReactDOM.render(element, document.getElementById("root"));

Live Demo: React Element on CodeSandbox

The thing I like about using JavaScript to generate these elements is that I didn’t need any special syntax to map over the array. Instead, I just used array.map.

I didn’t need a templating language to give me some ‘repeat’ or ‘mapping’ or ‘each’ syntax to loop over the array. I can use JavaScript which I already know.

Another thing that’s interesting here is that this person object was already in scope. So, I didn’t need a templating language to give me that concept of scope. I just use the person object in the JavaScript function scope. There’s nothing new to learn here.

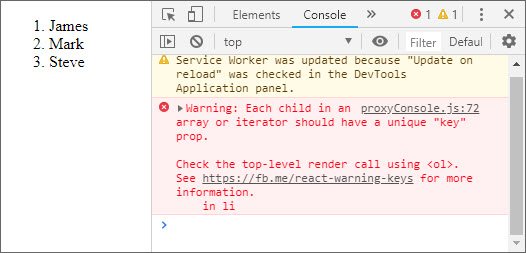

Now one thing to note, when you’re using an array as children is that React is going to complain if you don’t give it a key.

If we look at the console here in the browser, you’ll see a warning.

Each child in an array or iterator should have a unique “key” prop. Check the top-level render call using ol.

What does that mean? Well, remember, when we added the class name to the div, the second argument which we assigned a null to, is for props to our component.

So, let’s give this item a unique key prop. Something that is unique about each of these objects. In this case, the name would work because that’s unique for each of the objects.

import React from "react";

import ReactDOM from "react-dom";

const people = [{ name: "James" }, { name: "Mark" }, { name: "Steve" }];

const element = React.createElement(

"ol",

null,

people.map(person =>

React.createElement("li", { key: person.name }, person.name)

)

);

ReactDOM.render(element, document.getElementById("root"));

Live Demo: React Element on CodeSandbox

So, you’ll notice here that the warning goes away. Now, we’re not going to go too deep nto the key prop in this lesson. But know that if you are mapping over an array with React and you’re creating elements for each item in that array, each element needs its own unique key prop.

.createElement() Returns only One Root Element

Recall that React.createElement(); creates a single React element of a particular type. We’d normally pass in a tag such as a <div> or a <span> to represent that type, but the content argument can be another React element.

Consider the following example:

const element = React.createElement('div', null,

React.createElement('strong', null, 'Hello world!')

);

Here, “Hello world!” will be wrapped in a <div> when this React element renders as HTML. While we can indeed nest React elements, remember the overall call just returns a single element.

JSX

Now that we’ve learned how to create elements and how to nest them, it can get pretty tedious if we’re just using these nested create element calls to create large portions of our app.

What we need is an HTML-like syntax that we can use in our JavaScript.

This is exactly what JSX does.

JSX is a syntax extension to JavaScript, that lets us write JavaScript code that looks a little bit more like HTML, making it more concise and easier to follow. Let’s check it out.

import React from 'react';

import ReactDOM from 'react-dom';

import './styles.css';

const people = [{ name: 'James' }, { name: 'Mark' }, { name: 'Steve' }];

const element = (

<ol>

<li>{people[0].name}</li>

</ol>

);

ReactDOM.render(element, document.getElementById('app'));

Whenever we want JSX to evaluate some JavaScript for us, we have to wrap that piece of JavaScript in curly braces. This could be any JavaScript expression you want including some math, a ternary, or any other valid JavaScript.

Let’s create our list again. Everything between curly braces is JavaScript and everything between angle brackets is JSX. The code alternates between the two but is much more concise than the nested createElement calls.

import React from 'react';

import ReactDOM from 'react-dom';

import './styles.css';

const people = [{ name: 'James' }, { name: 'Mark' }, { name: 'Steve' }];

const element = (

<ol>

{people.map(person => (

<li key={person.name}>{person.name}</li>

))}

</ol>

);

ReactDOM.render(element, document.getElementById('app'));

Live Demo: React Simple JSX on CodeSandbox

As we said earlier whenever we give React an array, we need to give a unique key prop to each one of the repeating elements, list item in this case.

You’ll notice it looks like we’re assigning values to HTML attributes. We do this by opening up a JavaScript expression and using person.name as the value of the key prop.

Another thing to note is that event though we’re using JSX which is nice and concise, this code gets compiled down to real JavaScript using createElement inside our ‘bundle.js’.

2.2 Question 3 of 3

Consider the following example in JSX:

const greeting = (

<div className='greeting'>

<h2>Hello world!</h2>

</div>

);

If we want to output the same HTML, what goes into 1, 2, and 3 when calling createElement()?

const greeting = React.createElement(

__1__,

{ className: 'greeting' },

React.createElement(

__2__,

{},

__3__

)

);

- ‘h2’, ‘div’, ‘Hello world!’

- ‘div’, ‘h2’, ‘Hello world!’

- ‘div’, ‘h2’, ‘Hello world!’

- ‘Hello world’, ‘div’, ‘h2’

JSX returns One main element, too

When writing JSX, keep in mind that it must only return a single element. This element may have any number of descendants, but there must be a single root element wrapping your overall JSX (typically a <div> or a <span>). Check out the following example:

const message = (

<div>

<h1>All About JSX:</h1>

<ul>

<li>JSX</li>

<li>is</li>

<li>awesome!</li>

</ul>

</div>

);

See how there’s only one <div> element in the code above and that all other JSX is nested inside it? This is how you have to write it if you want multiple elements. To be completely clear, the following is incorrect and will cause an error:

const message = (

<h1>All About JSX:</h1>

<ul>

<li>JSX</li>

<li>is</li>

<li>awesome!</li>

</ul>

);

In this example, we have two sibling elements that are both at the root level (i.e. <h1> and <ul>) . This won’t work and will give the error:

Syntax error: Adjacent JSX elements must be wrapped in an enclosing tag

Since we know that JSX is really just a syntax extension for .createElement(), this makes sense; .createElement() takes in only one tag name (as a string) as its first argument.

Intro to Components

So far we’ve seen how .createElement() and JSX can help us produce some HTML. Typically, though, we’ll use one of React’s key features, Components, to construct our UI. Components refer to reusable pieces of code ultimately responsible for returning HTML to be rendered onto the page. More often than not, you’ll see React components written with JSX.

Since React’s main focus is to streamline building our app’s UI, there is only one method that is absolutely required in any React component class: render().

React provides a base component class that we can use to group many elements together and use them as if they were one element.

You could think about React components as the factories that we use to create React elements. So, by building custom components or classes, we can easily generate our own custom elements.

Let’s go ahead and build our first component class!

import React from 'react';

import ReactDOM from 'react-dom';

import './styles.css';

class ContactList extends React.Component {

render() {

const people = [{ name: 'Greg' }, { name: 'Mark' }, { name: 'Steve' }];

return (

<ol>

{people.map(person => (

<li key={person.name}>{person.name}</li>

))}

</ol>

);

}

}

ReactDOM.render(<ContactList />, document.getElementById('app'));

Live Demo: First Component on CodeSandbox

💡 Declaring Components in React 💡

In the previous video, we defined the ContactList component like so:

class ContactList extends React.Component { // ... }In other words, we are defining a component that’s really just a JavaScript class that inherits from React.Component.

In real-world use (and throughout this course), you may also see declarations like:

class ContactList extends Component { // ... }Both ways are functionally the same, but be sure your module imports match accordingly! That is, if you choose to declare components like the example directly above, your import from React will now look like:

import React, { Component } from 'react';

Creating Elements Recap

In the end, remember that React is only concerned with the View layer of our app. This is what the user sees and interacts with. As such, we can use .createElement() to render HTML onto a document. More often than not, however, you’ll use a syntax extension to describe what your UI should look like. This syntax extension is known as JSX, and just looks similar to plain HTML written right into a JavaScript file. The JSX gets transpiled to React’s .createElement() method that outputs HTML to be rendered in the browser.

A great mindset to have when building React apps is to think in components. Components represent the modularity and reusability of React. You can think of your component classes as factories that produce instances of components. These component classes should follow the single responsibility principle and just “do one thing”. If it manages too many different tasks, it may be a good idea to decompose your component into smaller subcomponents.

2.2 Further Research

- Rendering Elements from the React docs

2.3 Create React App

Skip past these older instruction to see how Create React App is installed on newer versions of node.js.

Old instructions (for reference)

💡Before Installing create-react-app💡

If you already have Node.js on your machine, it might be a good idea to upgrade or reinstall to make sure you have the latest version. Keep in mind that Node.js now comes with npm by default.

MacOS

- Install Homebrew by running

/usr/bin/ruby -e "$curl -fsSL https://raw.githubusercontent.com/Homebrew/install/master/install)"in the terminal

- Check that it was installed by running

brew --version. You should see the version number that was installed.- Run

brew install node.- Run

node --version.- Check that npm was installed as well by running

npm --version.- Run

brew install yarn --without-node.- Run

npm --version.- Run

yarn install && yarn --versionWindows

- Please download the Node.js Installer, go through the installation process, and restart your computer once you’re done.

- Please follow the yarn installation instructions.

- Run

yarn --versionto make sure yarn has been successfully installed.Linux

- Please follow these instructions to install Node.js.

- Run

sudo apt-get install -y build-essential.- Please follow the yarn installation instructions.

- Run

yarn --versionto make sure yarn has been successfully installed.Install create-react-app globally

Install Create React App (through the command-line with npm).

npm install -g create-react-appIf get permission errors, check out this article on global package installs in the npm documentation.

Note that to find out where global packages are installed, you can run

npm list -g --depth=0in your console (more information here).

What is Create React App

JSX is awesome, but it does need to be transpiled into regular JavaScript before reaching the browser. Typically this is done with two tools.

- Babel - a transpiler which converts JSX & ES6 to vanilla JavaScript

- Webpack - a build tool which bundles all our assets (JavaScript, CSS, images, etc.) for web projects

To streamline this initial configuration, Facebook published Create React App to manage the setup for us!

This tool is incredibly helpful to get started in building a React app, as it sets up everything we need with zero configuration!

The Create React App - Quick Overview shows how to use this tool to scaffold a React project without having to do a global install which was detailed in the old instructions.

Scaffolding Your React App

Let’s do the following:

npx create-react-app contacts

cd contacts

npm start

Now, create-react-app installs react, react-dom, and the react-scripts package.

React-scripts encapsulates a lot of powerful libraries.

- It installs Babel so we can use the latest JavaScript syntax as well as JSX.

- It also installs Webpack, so we can generate the build

- It installs Webpack dev server, which gives us the auto-reload behavior we’ve seen up until this point.

As with all abstractions, you can peel back the layers on react-scripts one at a time, if you really want to see what’s under the hood. But for now, create-react-app is a great way to get started quickly with the latest technologies without having to put in all the time needed to learn them before you get started with React.

The Yarn Package Manager

Both in the following video and in the output of create-react-app, we’re told to use yarn start to start the development server.

Yarn is a package manager that’s similar to NPM. Yarn was created from the ground up by Facebook to improve on some key aspects that were slow or lacking in NPM.

If you don’t want to install Yarn, you don’t have to! What’s great about it is that almost every use of yarn can be swapped with npm and everything will work just fine! So if the command is yarn start, you can use npm start to run the same command.

create-react-app Recap

Facebook’s create-react-app is a command-line tool that scaffolds a React application.

Using this, there is no need to install or configure module bundlers like Webpack, or transpilers like Babel. These come preconfigured (and hidden) with create-react-app, so you can jump right into building your app!

Check out these links for more info about create-react-app:

- create-react-app on GitHub

- create-react-app Release Post from the React blog

- Updates to create-react-app from the React blog

2.4 Composing with Components

Earlier, we said that components are the building blocks of React. But what is actually meant by that?

If you look at the API and documentation for React, they’re relatively small. The vast majority of React’s API is all about components. They are the main unit of encapsulation that React gives us.

Components are great, because they help us break down the UI into smaller pieces. These pieces have clear responsibilities and well-defined interfaces. This is valuable when building a large app, because it lets us work on tiny pieces of the app without inadvertently affecting the rest of it.

Another great thing about components, is that they encourage us to build applications using composition instead of inheritance.

So, let’s talk a little bit about what it means to use composition to build user interfaces and how React let’s us do that.

We open up the index.js and paste in the <ContactList /> component. And instead of rendering everything inside of the App, I’m going to render it the ContactList.

import React from 'react';

import ReactDOM from 'react-dom';

class ContactList extends React.Component {

render() {

const people = this.props.contacts;

return (

<ol>

{people.map(person => (

<li key={person.name}>{person.name}</li>

))}

</ol>

);

}

}

function App() {

return (

<div className="App">

<ContactList />

<ContactList />

<ContactList />

</div>

);

}

const rootElement = document.getElementById('root');

ReactDOM.render(<App />, rootElement);

Live Demo: Simple Composition on CodeSandbox

We can already see how easy it is to create our own custom elements as we’ve talked about before, and compose them together. We can take the ContactList and put it right inside the application.

Encapsulating many elements inside of a component gives us a few advantages.

For one, it’s really easy to reuse all of those elements. For example, if I wanted multiple copies of the ContactsLists, I could just copy and paste this line three times and get three identical copies of those elements.

Another nice property of these components is that they have a very clean interface so I can configure different components differently just by giving them different props.

Take for example, our ContactList. Let’s say, in the first ContactList I want to show three names and in the second contact list, I want to show a completely different set of contacts.

So what I would actually like to do is to be able to configure these ContactLists independently of one another. We can do this with the use of prop that we pass each ContactList component.

import React from 'react';

import ReactDOM from 'react-dom';

class ContactList extends React.Component {

render() {

const people = this.props.contacts;

return (

<ol>

{people.map(person => (

<li key={person.name}>{person.name}</li>

))}

</ol>

);

}

}

function App() {

return (

<div className="App">

<ContactList

contacts={[{ name: 'James' }, { name: 'Mark' }, { name: 'Steven' }]}

/>

<ContactList

contacts={[{ name: 'Evi' }, { name: 'Sarah' }, { name: 'Susan' }]}

/>

<ContactList

contacts={[{ name: 'Spot' }, { name: 'Rover' }, { name: 'Fido' }]}

/>

</div>

);

}

const rootElement = document.getElementById('root');

ReactDOM.render(<App />, rootElement);

Live Demo: Simple Composition on CodeSandbox

You can see we were able to reuse the elements from ContactList but configure them completely separately. This makes it really easy to reuse these components by just passing in little bits of configuration via the props.

These two principles,

- the ability to encapsulate a bunch of elements in a component

- the ability to easily reuse each component by being able to configure each one differently and independently via props

are two really important and fundamental keys to understanding the composition model of React.

Favor Composition Over Inheritance

You might have heard before that it’s better to “favor composition over inheritance”. This is a principle that I believe is difficult to learn today. Many of the most popular programming languages make extensive use of inheritance, and it has carried over into popular UI frameworks like the Android and iOS SDKs.

In contrast, React uses composition to build user interfaces. Yes, we extend React.Component, but we never extend it more than once. Instead of extending base components to add more UI or behavior, we compose elements in different ways using nesting and props. You ultimately want your UI components to be independent, focused, and reusable.

So if you’ve never understood what it means to “favor composition over inheritance” you’ll definitely learn using React!

2.5 Component Recap

The principles we’ve discussed in this lesson are absolutely fundamental to getting the most out of a React.

Just to recap…

- We learned about how JSX just uses JavaScript to let us describe the UI by creating elements instead of writing these rigid string templates.

- We also learned how to encapsulate groups of elements in React components, and how to build larger portions of the UI by composing those components together.

-

Components let you split the UI into independent, reusable pieces, and think about each piece in isolation.

-

Conceptually, components are like JavaScript functions. They accept arbitrary inputs (called “props”) and return React elements describing what should appear on the screen.

-

- We also installed Create React App, and used it to get a quick start on using the latest technologies commonly used to create a modern React application.

But React’s code we use in encapsulation story gets really interesting in the next lesson where we talk about how each of these little components can hold, and manage it’s own state.

3. State Management

3.1 Project Setup

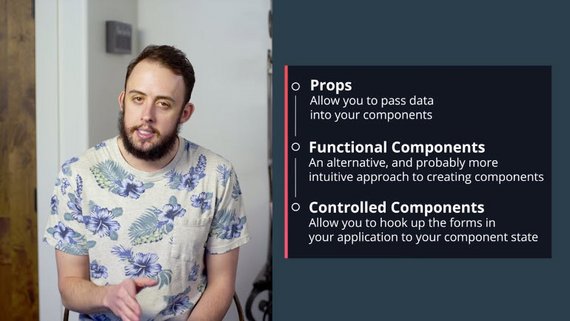

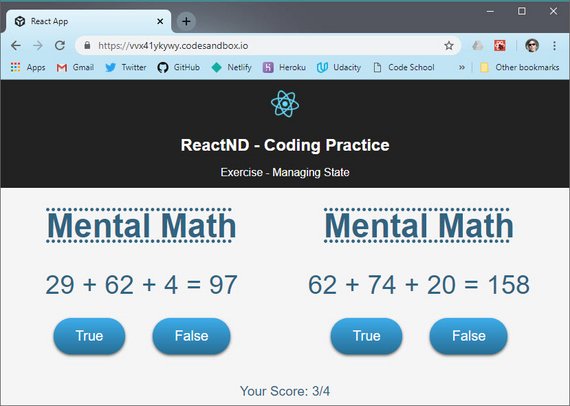

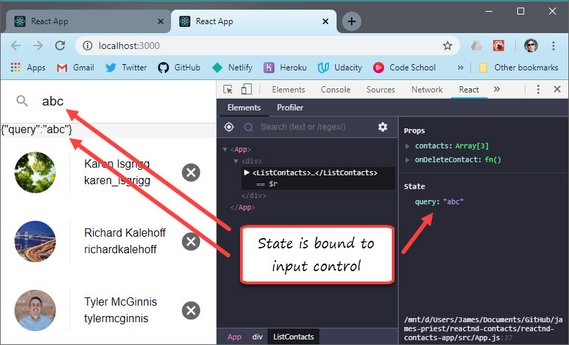

Three new concepts that we’ll be covering are:

- Props - Allows you to pass data into components

- Functional Components - An alternative, and probably more intuitive approach to creating components.

- Controlled Components - Allows you to hook up the forms in your application to your component state

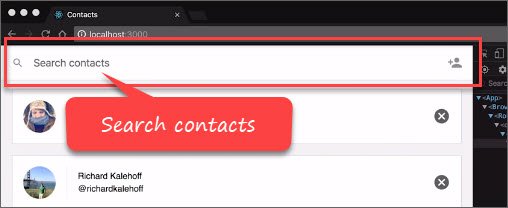

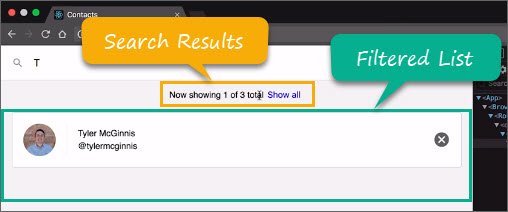

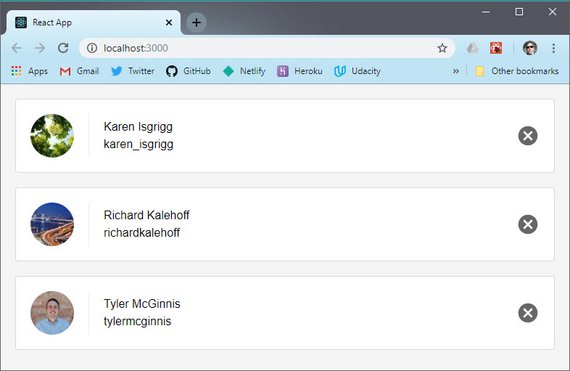

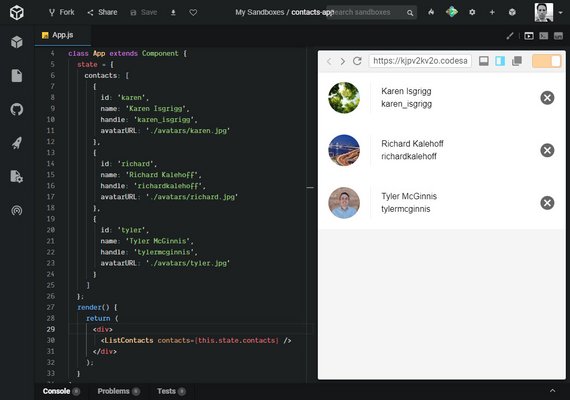

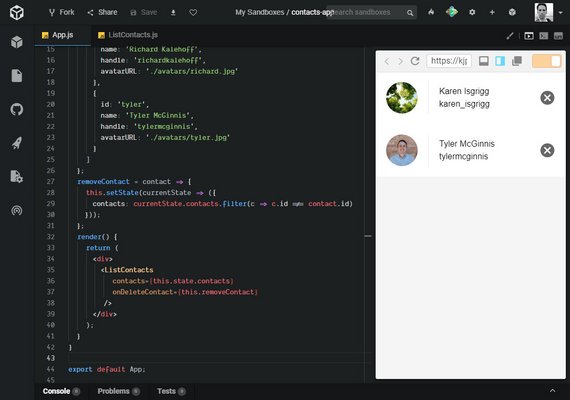

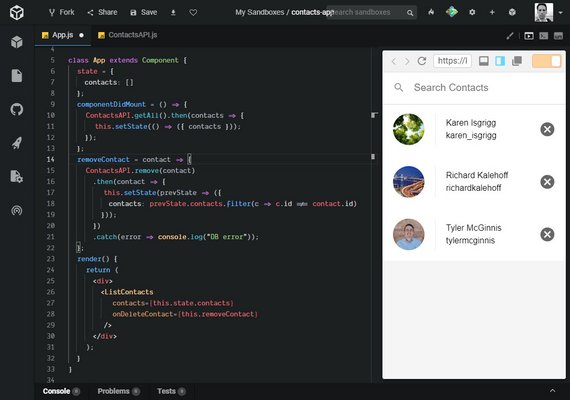

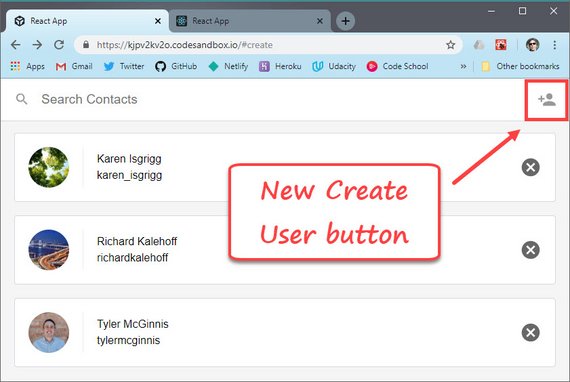

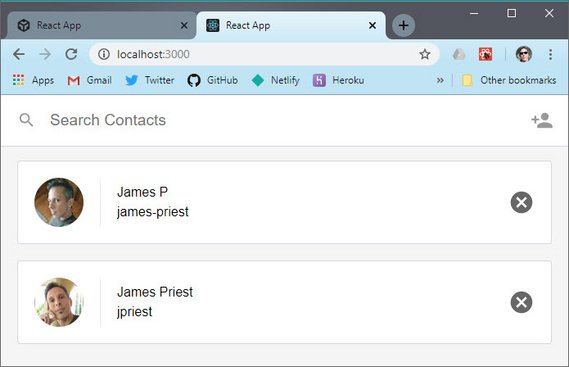

Contacts App

We will be building a Contacts app that shows a list of contacts. Each contact has an avatar, name, and twitter handle.

The app will also have a search bar that will allow you to filter the contacts or reset the the state to show all contacts.

It will also allow you to remove a contact and add a contact by entering a name, handle, and uploading an image.

What we should think about is how to build out this application. The way we build a large React application is by building out a bunch of small applications or components.

We need to consider how we’d structure this out if we were building this out of components.

Front End Project Files

Create React App will generate a number of default files and starter code that we need to get rid of. There will be two sets of changes you need to make, delete the starter content and add files that we’re providing you.

We’ve done this step this for you. Here’s the project repo

Follow these instructions.

- Clone the repo with

git clone https://github.com/udacity/reactnd-contacts-app.git

- checkout the ‘starter-files-added’ remote branch with this command

git checkout -b starter-files-added origin/starter-files-added

Back End Server

The Contacts app project that we’re building is a front-end project. However, we’ll eventually be storing the contacts on a backend server. Since we’re only really focusing on the front-end for this course, we’ve gone ahead and built this server for you so you can focus on just the React parts of this program.

The server is a simple Node/Express app. The repo for the project is at

All you need to do is:

- clone the project with

git clone https://github.com/udacity/reactnd-contacts-server2.git

- install the project dependencies with

npm install

- start the server with

node server.js

Once you’ve started the server, you can forget about it. The Contacts project we’re working on will interact with this server, but we won’t ever modify any of the server code.

💡 Running Two Servers💡

At this point, you should be running two different servers on your local machine:

- Front-end development server: Accessible on port 3000

- (

npm startoryarn start)- Back-end server: Accessible on port 5001

- (

node server.js)Please be sure that both are running before moving on in this Lesson.

3.2 Pass Data with Props

Here we have a function whose whole purpose is to fetch a user. The problem is we need to tell the function which user to fetch. This is done by passing a parameter to our function.

The same thing holds true for React components. In the same way we pass data to a function, we can pass data to a component.

Here the whole purpose of this component is to display a user to the UI. In order to do this we add a custom attribute to our component and give it a value.

Now we can access that value from inside our component definition by using this.props.username.

In fact any attributes that are added to a component are accessible inside of that component.

Here we’ll use this contacts array temporarily. Eventually, we’ll be grabbing this from our backend server.

const contacts = [

{

"id": "karen",

"name": "Karen Isgrigg",

"handle": "karen_isgrigg",

"avatarURL": "http://localhost:5001/karen.jpg"

},

{

"id": "richard",

"name": "Richard Kalehoff",

"handle": "richardkalehoff",

"avatarURL": "http://localhost:5001/richard.jpg"

},

{

"id": "tyler",

"name": "Tyler McGinnis",

"handle": "tylermcginnis",

"avatarURL": "http://localhost:5001/tyler.jpg"

}

];

We want to create a new component that will take in this array as props and be responsible for looping over that array to show a contact record for each item in the array.

Whenever we want to build out a new component we create a new file for it. In this case we’ll want to name the file “ListContacts.js” because that’s what the component will be responsible for.

ListContacts - array as props

We start with our import statement. Then we create our class and extend Component. We’ll usually want to immediately jump down to the bottom and do our export statement as well.

// ListContacts.js

import React, { Component } from 'react';

class ListContacts extends Component {

render() {

return (

<ol className="contact-list">

</ol>

)

}

}

export default ListContacts;

We create the render method and inside our return statement and we start with an ordered list.

Next we need to figure out a way of passing the array from App to our child component.

We first start by importing our ListContacts component. We are then able to use it in our App’s render method. We then create a contacts prop and pass in the contacts array.

// App.js

import React, { Component } from 'react';

import ListContacts from './ListContacts';

const contacts = [

{

id: 'karen',

name: 'Karen Isgrigg',

handle: 'karen_isgrigg',

avatarURL: 'http://localhost:5001/karen.jpg'

}

// additional elements...

];

class App extends Component {

render() {

return (

<div>

<ListContacts contacts={contacts} />

</div>

);

}

}

export default App;

We can think of this as we would a function invocation. We can pass data to that function in the same way we’re passing data to our component as a prop.

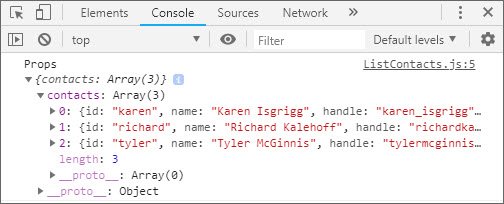

Lastly if we want to test we can console.log the following in ListContacts.js and view this in our Console.

class ListContacts extends Component {

render() {

console.log('Props', this.props);

return (

<ol className="contact-list">

</ol>

);

}

}

Argument is to function what props is to component.

3.2 Question 2 of 4

If there were a <Clock /> component in an app you’re building, how would you pass a currentTime prop into it?

<Clock {new Date().getTime()} /><Clock this.props={new Date().getTime()} /><Clock currentTime={new Date().getTime()} /><Clock this.currentTime={new Date().getTime()} />

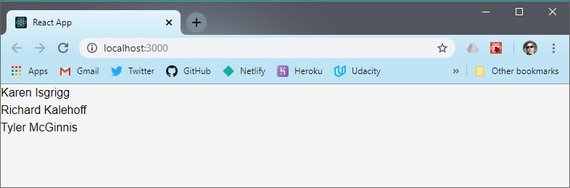

ListContacts - map over array

Next we map over the contacts array and create a list item outputting the name for each. We create a key attribute and output the id.

class ListContacts extends Component {

render() {

return (

<ol className="contact-list">

{this.props.contacts.map(contact => (

<li key={contact.id}>

{contact.name}

</li>

))}

</ol>

);

}

}

Notice that we use a parens instead of curly braces after the ES6 arrow function in order to get the implicit return.

The reason we need to add a key is because eventually one of those list items may change, and by having a unique key attribute on each list item, React is able to performantly know which list item has changed and can update just that item rather than having to recreate the entire list every time.

3.2 QUESTION 3 OF 4

Using the <Clock /> component example:

<Clock currentTime='3:41pm' />

How would you access the value 3:41pm from inside the component?

- Clock.currentTime

- currentTime

- this.currentTime

- this.props.currentTime

ListContacts - display data & inline style

Now instead of just showing the names, we want to fill out the rest of the component.

We start by adding a className to the list item. We then create a div which will be used for the avatar. We’ll want to add an inline style to this div so we can pass in the specific image url for this avatar that is contained in our contacts array.

The style attribute has two curly braces. The first tells React that we’re using JavaScript and the second is the object that we’re passing in with the inline style rules.

Then we create another div to contain paragraph elements for the name and handle.

class ListContacts extends Component {

render() {

return (

<ol className="contact-list">

{this.props.contacts.map(contact => (

<li key={contact.id} className="contact-list-item">

<div

className="contact-avatar"

style={{

backgroundImage: `url(${contact.avatarURL})`

}}

/>

<div className="contact-details">

<p>{contact.name}</p>

<p>{contact.handle}</p>

</div>

<button className="contact-remove">Remove</button>

</li>

))}

</ol>

);

}

}

Lastly, we create a button for the Remove action which is not hooked up yet.

Live Demo: Contacts App on CodeSandbox

3.2 Question 4 of 4

How do you pass multiple props individually to a component?

<Clock time={Date.now()} zone='MST' /><Clock props={{time: Date.now(), zone: 'MST'}} /><Clock [time=Date.now(), zone='MST'] /><Clock props={[Date.now(), 'MST']} />

Passing Data With Props Recap

A prop is any input that you pass to a React component. Just like an HTML attribute, a prop name and value are added to the Component.

// passing a prop to a component

<LogoutButton text='Wanna log out?' />

In the code above, text is the prop and the string ‘Wanna log out?’ is the value.

All props are stored on the this.props object. So to access this text prop from inside the component, we’d use this.props.text:

// access the prop inside the component

...

render() {

return <div>{this.props.text}</div>

}

...

3.2 Further Research

- Components and Props from the React Docs

3.3 Exercise Prep

Workspaces

In this program, you’ll be able to practice what you’ve learned right inside the classroom!

A Workspace is a development environment integrated into the Udacity Classroom. Your Workspace is backed by a Linux virtual machine (Ubuntu). You have access to a terminal, so you have complete control over installing packages and modifying content.

Exercises in Workspaces

Each Workspace contains an instructions.md file that contains the instructions for the exercise. Each Workspace also contain a Possible Solution folder located inside of the src folder. We recommend not looking inside the Possible Solution folder until you have finished the exercise on your own. That way, you can practice recalling and applying what you’ve learned, thereby solidifying your understanding of the material.

Preservation Information

The first time you open your Workspace, a new virtual machine is created just for you. Any files that you modify in /home/workspace or any new files you add in /home/workspace are automatically backed up and saved. The next time you come back to the Workspace, any previous changes will be preserved.

If you don’t interact with the Workspace for 30 minutes, the Workspace will be suspended. The Workspace becomes idle by any of the following:

- not interacting with the browser tab of the Workspace

- closing the browser tab with the Workspace

- if your laptop goes to sleep

- etc

Restoring Your Workspace

If your Workspace has been suspended after a period of inactivity, just click the “Wake Up Workspace” button to restore it. Remember that none of your data is lost.

Project Development

Think of your Workspace as a normal computer:

- Open up the files you need to edit (saving is done automatically).

- Open terminal windows as necessary.

- The terminal should start at /home/workspace, so make sure to cd to the correct directory as necessary.

- Start the project

- start a terminal (no need to cd anywhere)

- run

npm install0- runnpm start

- Open the src folder and start working on the exercise.

- To view your project, click the “Open Preview Tab” button located in the lower left of the screen.

- Running

npm startcauses Create React App to display a URL of http://localhost:3000/. Because your Workspace is running in a virtual machine, typing http://localhost:3000/ into your browser will not access the local host of the VM, so make sure to use the “Open Preview Tab” button.

- Running

Committing to Github

We strongly recommend committing your files to Github whenever you’re working on coding projects. Workspaces provide a convenient way to do that - just use the Workspace Terminal.

To commit files from your Workspace directly to Github:

- Set up a new Github repository.

- Use the Workspace terminal to commit files to Github as usually would. If you need a refresher, click here. Don’t forget to add your

node_modulesfolder to the.gitignorefile.

Unable to Access Your Workspace?

If you are unable to access your Workspace in the Classroom it could be because you have “3rd Party Cookies” disabled in your browser. Workspaces need to set a “3rd party cookie” to enable access.

Check out this Workspace troubleshooting FAQ for information on how to enable 3rd party cookies for your browser.

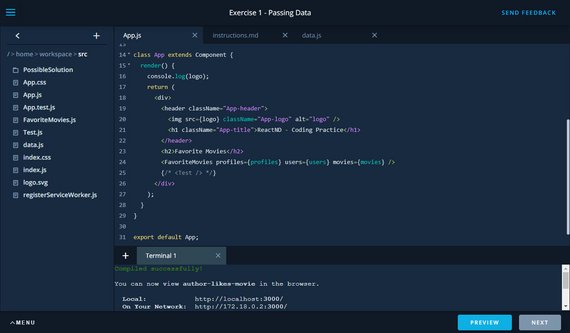

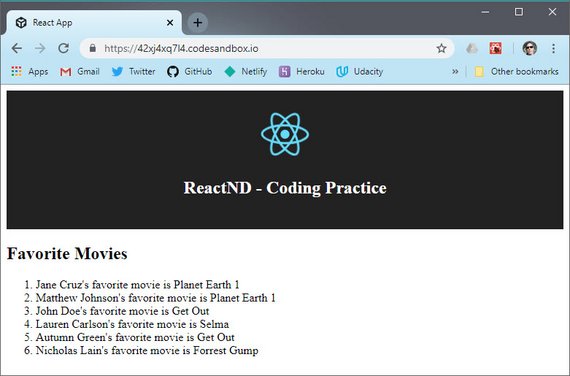

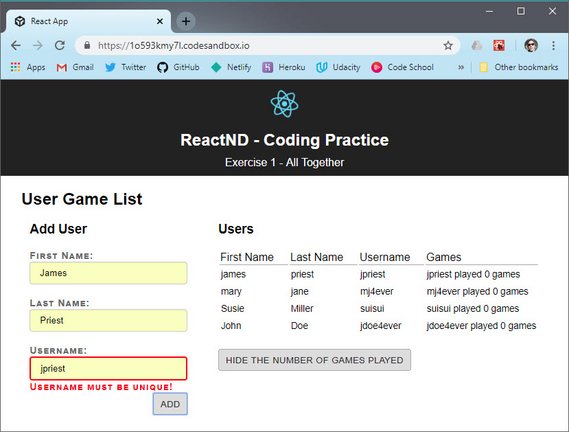

3.4 Ex 1 - Passing Data

This exercise consisted of the following instructions.

Instructions

Use React and the

profiles,users, andmoviesdata in App.js to display a list of users alongside their favorite movies.Example

Jane Cruz’s favorite movie is Planet Earth 1.

The data looks like this.

// data.js

const profiles = [

{

id: 1,

userID: '1',

favoriteMovieID: '1',

},

// more records...

];

const users = {

1: {

id: 1,

name: 'Jane Cruz',

userName: 'coder',

},

// more records...

};

const movies = {

1: {

id: 1,

name: 'Planet Earth 1',

},

// more records...

};

export {profiles, users, movies};

3.4 Solution

The entry point is index.jsx. It imports our styles.css and App component and then renders that App component.

// index.js

import React from 'react';

import ReactDOM from 'react-dom';

import App from './App';

import './styles.css';

const rootElement = document.getElementById('root');

ReactDOM.render(<App />, rootElement);

App will act as the parent component. It imports data.js and passes that data as props to the FavoriteMovies component.

// App.js

import React, { Component } from 'react';

import './App.css';

import FavoriteMovies from './FavoriteMovies';

import { profiles, users, movies } from './data.js';

class App extends Component {

render() {

return (

<div>

<header className="App-header">

<img src="logo.svg" className="App-logo" alt="logo" />

<h1 className="App-title">ReactND - Coding Practice</h1>

</header>

<h2>Favorite Movies</h2>

<FavoriteMovies profiles={profiles} users={users} movies={movies} />

</div>

);

}

}

export default App;

The FavoriteMovies component maps over the props data and gets both user’s name and the movie name from the lookup object stores.

// FavoriteMovies.js

import React, { Component } from 'react';

class FavoriteMovies extends Component {

render() {

const { profiles, users, movies } = this.props;

return (

<ol>

{profiles.map(profile => (

<li key={profile.id}>

{users[profile.userID].name}'s favorite movie is{' '}

{movies[profile.favoriteMovieID].name}

</li>

))}

</ol>

);

}

}

export default FavoriteMovies;

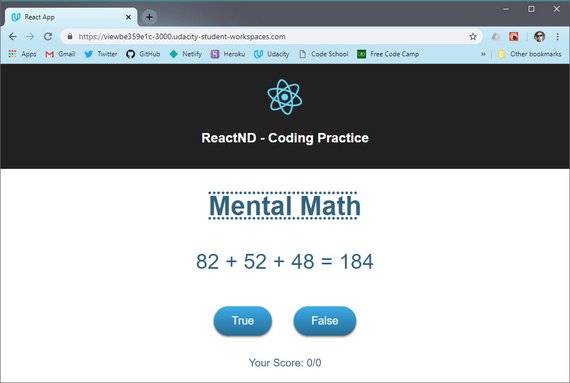

Here’s the final result.

Live Demo: Ex 1 - Passing Data on CodeSandbox

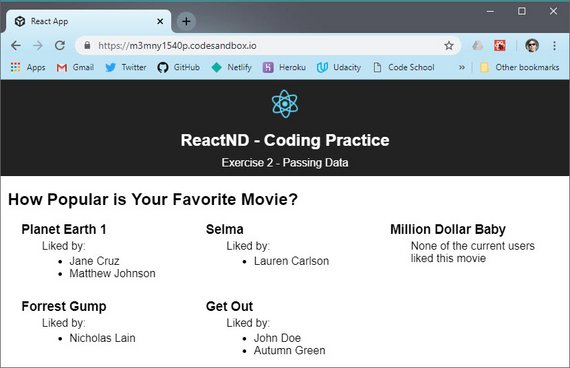

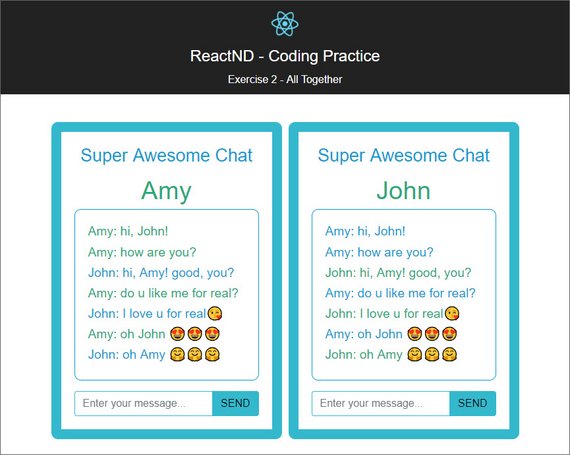

3.5 Ex 2 - Passing Data

The instructions for this exercise are:

3.5 Instructions

Let’s do something a little bit more complicated. Instead of displaying a list of users and their movies, this time you need to display a list of movies.

For each movie in the list, there are two options:

- If the movie has been favorited, then display a list of all of the users who said that this movie was their favorite.

- If the movie has not been favorited, display some text stating that no one favorited the movie.

As you go about tackling this project, try to make the app modular by breaking it into reusable React components.

3.5 Example

<h2>Forrest Gump</h2> <p>Liked By:</p> <ul> <li>Nicholas Lain</li> </ul> <h2>Get Out</h2> <p>Liked By:</p> <ul> <li>John Doe</li> <li>Autumn Green</li> </ul> <h2>Autumn Green</h2> <p>None of the current users liked this movie</p>

Same data as before.

// data.js

const profiles = [

{

id: 1,

userID: '1',

favoriteMovieID: '1',

},

// more records...

];

const users = {

1: {

id: 1,

name: 'Jane Cruz',

userName: 'coder',

},

// more records...

};

const movies = {

1: {

id: 1,

name: 'Planet Earth 1',

},

// more records...

};

export {profiles, users, movies};

3.5 Solution

The data is the same as the previous exercise except this time it had some more complexity.

It required one component to loop through the movies (PopularMovies). Then it required a child component (UserList) to display the names of people that favorited that movie.

Within App I just passed the profiles, users, movies as props to my FavoriteMovies component.

// App.js

import React, { Component } from 'react';

import './App.css';

import { profiles, users, movies } from './data.js';

import PopularMovies from './PopularMovies';

class App extends Component {

render() {

return (

<div className="App">

<header className="App-header">

<img src="logo.svg" className="App-logo" alt="logo" />

<h1 className="App-title">ReactND - Coding Practice</h1>

<p>Exercise 2 - Passing Data</p>

</header>

<main className="App-main">

<h2>How Popular is Your Favorite Movie?</h2>

<PopularMovies profiles={profiles} users={users} movies={movies} />

</main>

</div>

);

}

}

export default App;

Next I destructured props and created moviesArr from the movies object.

// PopularMovies.js

import React, { Component } from 'react';

import UserList from './UserList';

class PopularMovies extends Component {

render() {

const { profiles, users, movies } = this.props;

const moviesArr = Object.values(movies);

return (

<div className="PopularMovies-container">

{moviesArr.map(movie => (

<div key={movie.id} className="PopularMovies-cell">

<h3>{movie.name}</h3>

<UserList movieID={movie.id} users={users} profiles={profiles} />

</div>

))}

</div>

);

}

}

export default PopularMovies;

moviesArr follows this format:

[{id: 1, name: 'movie 1'}, {id:2, name: 'movie 2'}, ...]

Now I can map over the movies to output my movie name and pass the following to my UserList component.

- movieID

- users

- profiles

In UserList I filter the profiles array by returning only those users that have favorited the specific movieID we’re on.

// UserList.js

import React, { Component } from 'react';

class UserList extends Component {

render() {

const { movieID, profiles, users } = this.props;

const filteredProfiles = profiles.filter(

profile => Number(profile.favoriteMovieID) === movieID

);

// console.log(filteredProfiles);

if (!filteredProfiles || filteredProfiles.length === 0) {

return <p>None of the current users liked this movie</p>;

}

return (

<div>

<p>Liked by:</p>

<ul>

{filteredProfiles.map(profile => (

<li key={profile.userID}>{users[profile.userID].name}</li>

))}

</ul>

</div>

);

}

}

export default UserList;

Next, I check if no filteredProfiles array items exist then I output a message and return.

Otherwise I map over filteredProfiles and resolve the users.name based on the profile.userID.

Lastly I added some styling so it lays out nicely.

Live Demo: Ex 2 - Passing Data on CodeSandbox

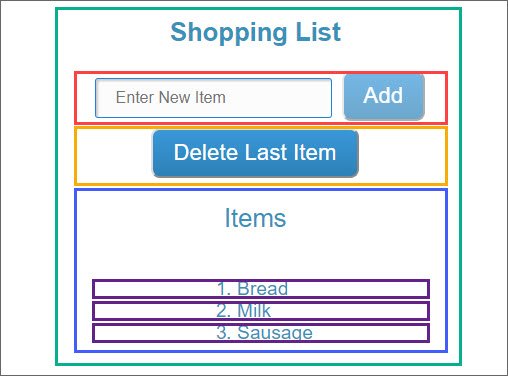

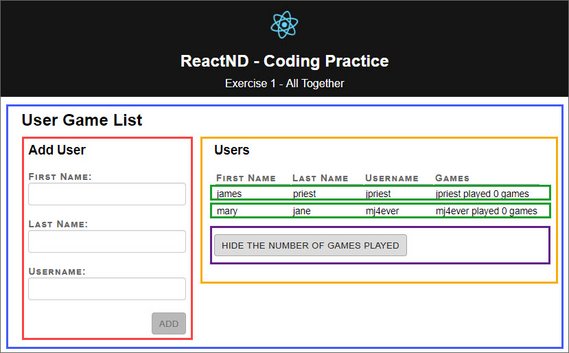

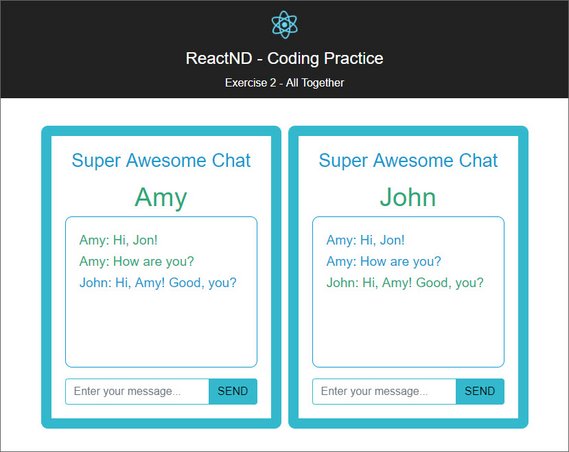

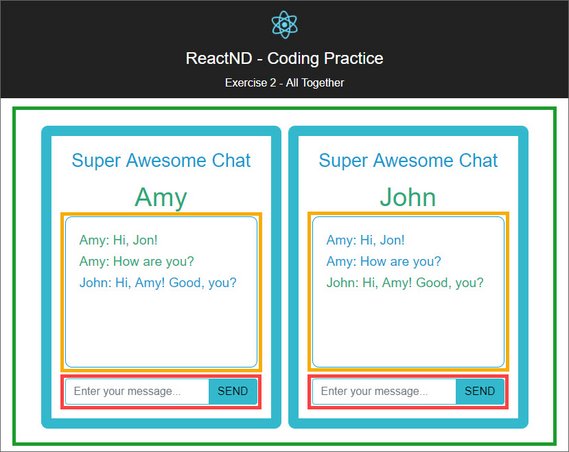

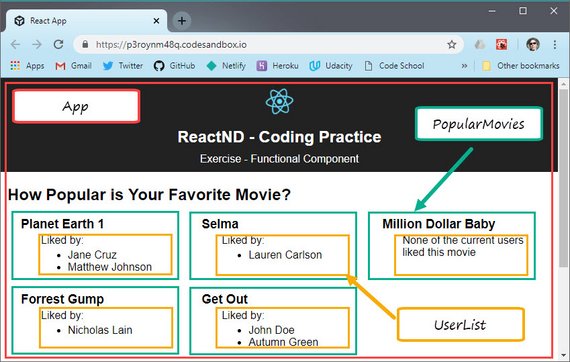

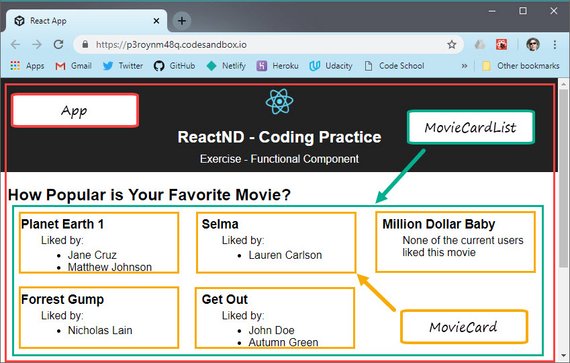

Here’s a diagram of how the various components lay out within the UI.

Live Demo: Ex 2 - Passing Data on CodeSandbox

3.6 Functional Components

Up until this point we’ve used JavaScript’s class syntax with a render() method to build out our components.

// class component

class User extends React.Component {

render() {

return (

<p>Username: {this.props.username}</p>

)

}

}

Eventually we’ll be adding more methods to these classes but if all our component has is a render() method then we can use a regular old function to render out our component.

// stateless functional component

function Username(props) {

return (

<p>Username: {props.username}</p>

)

}

Notice, however, that we’re no longer accessing the components props by using the ‘this’ keyword. Instead, our functional component is being passed its props as the first argument to the function.

3.6 Question 1 of 2

When is it appropriate to use a Stateless Functional Component? Check all that apply.

- When the component needs to initialize some data

- When all the component needs is to just render something

- When the component doesn’t have any props passed in

- When the component does not use JSX

3.6 Question 2 of 2

If the

<IngredientList items={ingredient.items} />

- props.items

We do away with the ‘this’ keyword.

Refactor ListContacts

Next we are going to refactor our ListContacts component following the rules above.

Here’s the component defined as a class.

// ListContact.js

import React, { Component } from 'react';

class ListContacts extends Component {

render() {

return (

<ol className="contact-list">

{this.props.contacts.map(contact => (

<li key={contact.id} className="contact-list-item">

<div

className="contact-avatar"

style={{

backgroundImage: `url(${contact.avatarURL})`

}}

/>

<div className="contact-details">

<p>{contact.name}</p>

<p>{contact.handle}</p>

</div>

<button className="contact-remove">Remove</button>

</li>

))}

</ol>

);

}

}

export default ListContacts;

After making our changes we have a slightly simpler component in the form of a stateless functional component.

// ListContact.js

import React from 'react';

function ListContacts(props) {

return (

<ol className="contact-list">

{props.contacts.map(contact => (

<li key={contact.id} className="contact-list-item">

<div

className="contact-avatar"

style={{

backgroundImage: `url(${contact.avatarURL})`

}}

/>

<div className="contact-details">

<p>{contact.name}</p>

<p>{contact.handle}</p>

</div>

<button className="contact-remove">Remove</button>

</li>

))}

</ol>

);

}

export default ListContacts;

This required us to drop the ‘this’ keyword and simply return the UI code from the function that takes props as it’s first argument.

Stateless Functional Components Recap

If your component does not keep track of internal state (i.e., all it really has is just a render() method), you can declare the component as a Stateless Functional Component.

Remember that at the end of the day, React components are really just JavaScript functions that return HTML for rendering. As such, the following two examples of a simple Email component are equivalent:

// class component

class Email extends React.Component {

render() {

return (

<div>

{this.props.text}

</div>

);

}

}

// stateless functional component

const Email = (props) => (

<div>

{props.text}

</div>

);

In the latter example (written as an ES6 function with an implicit return), rather than accessing props from this.props, we can pass in props directly as an argument to the function itself. In turn, this regular JavaScript function can serve as the Email component’s render() method.

3.6 Further Research

3.7 Ex - Fn Components

The exercise instructions are.

3.7 Instructions

Modify this app to use Stateless Functional Components. Remember that for performance reasons, if a component doesn’t need to hold state, we’d want to make it a Stateless Functional Component.

This exercise will help you practice passing data into Stateless Functional Components.

App.js

// before

class App extends Component {

render() {

return (

<div>

<header className="App-header">

<img src={logo} className="App-logo" alt="logo" />

<h1 className="App-title">ReactND - Coding Practice</h1>

</header>

<h1>How Popular is Your Favorite Movie?</h1>

<MovieCardsList profiles={profiles} movies={movies} users={users} />

</div>

);

}

}

// after

function App (props) {

return (

<div>

<header className="App-header">

<img src={logo} className="App-logo" alt="logo" />

<h1 className="App-title">ReactND - Coding Practice</h1>

</header>

<h1>How Popular is Your Favorite Movie?</h1>

<MovieCardsList profiles={profiles} movies={movies} users={users} />

</div>

)

}

MovieCardsList

//before

class MovieCardsList1 extends Component {

render() {

const { profiles, users, movies } = this.props;

const usersByMovie = {};

profiles.forEach(profile => {

const movieID = profile.favoriteMovieID;

if (usersByMovie[movieID]) {

usersByMovie[movieID].push(profile.userID);

} else {

usersByMovie[movieID] = [profile.userID];

}

});

const movieCards = Object.keys(movies).map(id => (

<MovieCard

key={id}

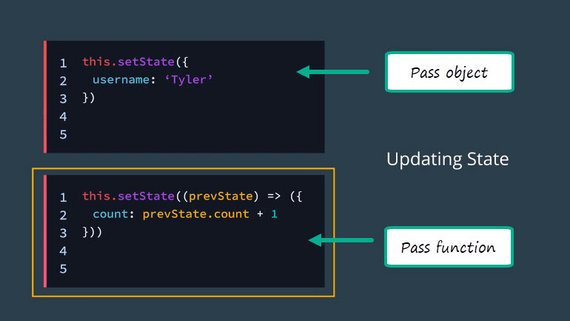

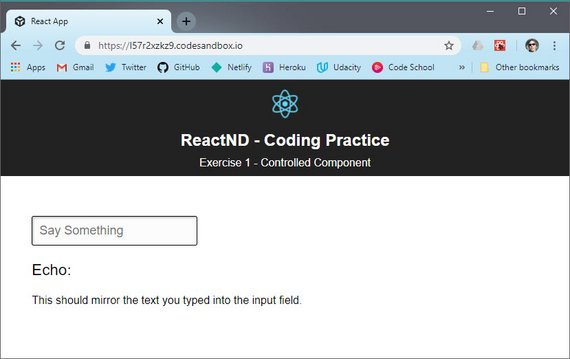

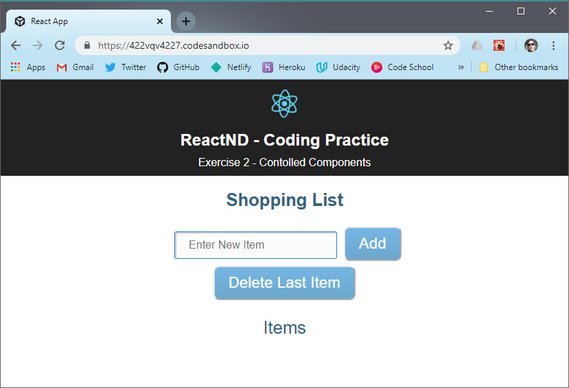

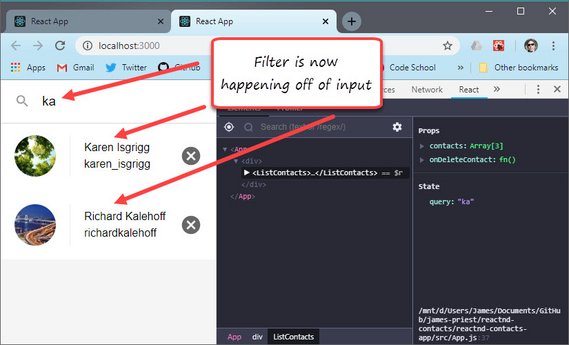

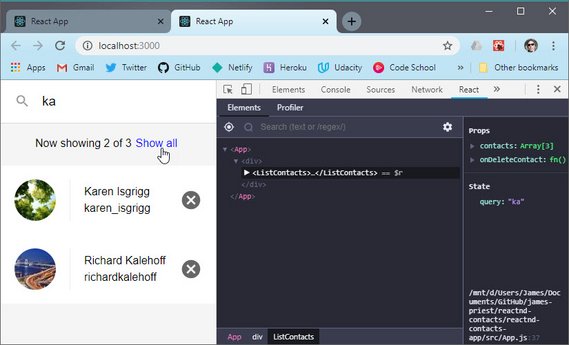

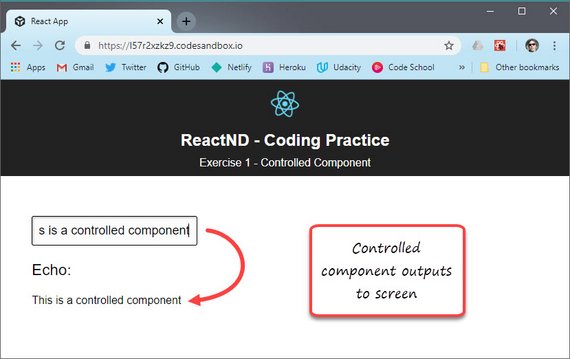

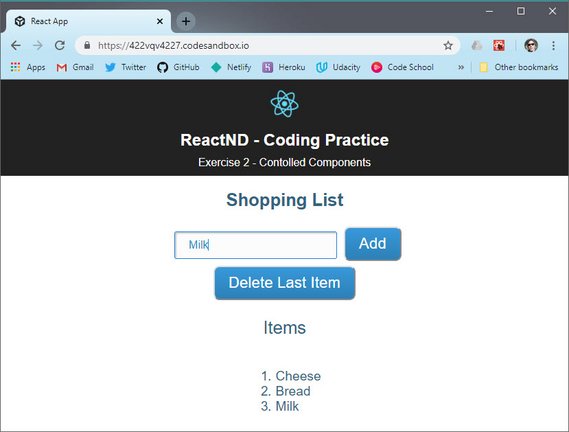

users={users}