Web Accessibility

<– back to Mobile Web Specialist Nanodegree homepage

Supporting Links

Sample Code

- Web Accessibility GitHub repo - Udacity’s GitHub repo for this course

Tools

- ChromeVox Screen Reader - Chrome browser extension by Google

- ChromeVox Lite Screen Reader - In-page sample screen reader by Google

WCAG

ARIA

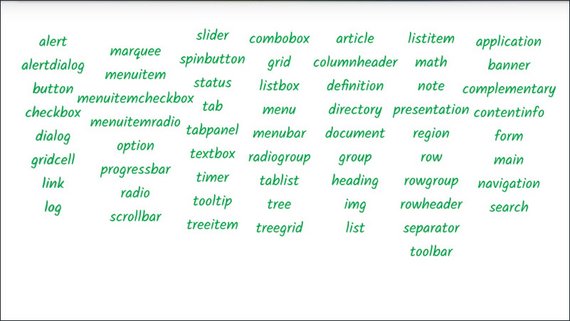

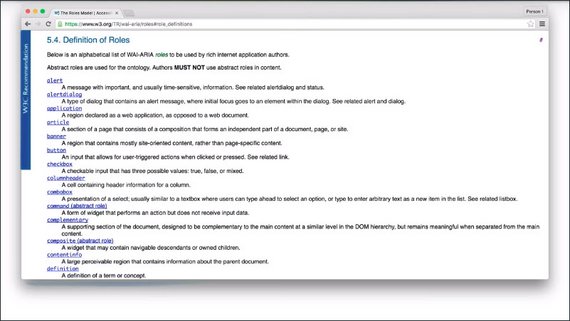

- ARIA 1.1 roles: https://www.w3.org/TR/wai-aria-1.1/#roles

- ARIA 1.1 practices guide: https://www.w3.org/TR/wai-aria-practices-1.1/

Lesson 10. Accessibility Overview

10.1 Intro to Accessibility

Alice Boxhall a software engineer on the Google Chrome accessibility team and Rob Dodson, a developer advocate for Chrome help you understand how you can make your websites accessible and usable for everyone.

Accessibility is a pain to spell. So we often shorten it “a11y”, but it doesn’t have to be a pain to work on. We’ll show you how you can get some easy wins to:

- help improve accessibility with minimal effort

- use what’s built into HTML to create more accessible and robust interfaces

- use some advanced techniques for creating really polished accessible experiences.

You’ll also see as we go that a great deal of this work will help you create interfaces which are more delightful and easy to use for everyone.

In fact, I think a lot of developers have only a pretty hazy understanding of what accessibility means, something to do with government contracts and checklists and screen readers.

There are plenty of misconceptions floating around, like a lot of developers feel that addressing accessibility is going to force them to choose between creating a delightful and attractive experience and ticking a box saying that their site is accessible.

So, what do we mean by accessibility and really like what are we here to learn about?

Well, broadly speaking when we say a site to be accessible, we’re saying that the site’s content should be available to everyone and functionality can be operated by anyone. Literally, that everyone should be able to access it.

When it comes to developing sites which are accessible by everyone, we need to be a bit more specific.

As developers, it’s easy to fall into the trap of assuming that all users can see and use a pointer interface like a mouse ora touch screen and experience your application the same way that you do. This can lead to creating an experience which might work well for a narrow range of people, but creates issues for anyone outside of that range.

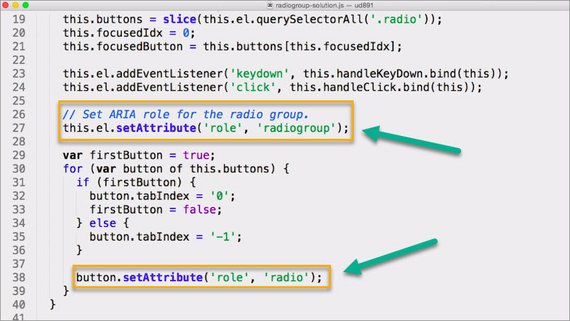

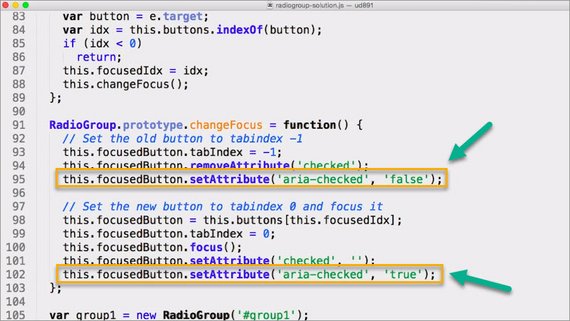

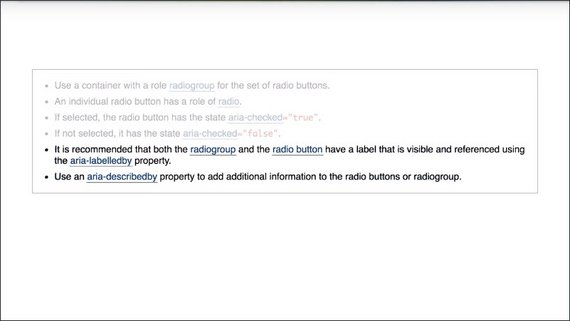

Accessibility in that case refers the experience of users who might be outside of that narrow range and who might access or experience things differently to the way the person we picture as a typical user would. Specifically, it concerns users who are experiencing some type of impairment or disability, and I say experiencing that, because it makes absolutely no difference whether that impairment is situational, temporary, or permanent.

So with that in mind, let’s explore what happens when we actually do takean inaccessible site and make it more accessible.

Introductory Notes

Welcome to the Web Accessibility course!

Good accessibility or “a11y” is crucial to making sure all users can access the content in your sites and applications. Making sure you consider accessibility at the start of your process will ensure that your final product is more polished and works for more people.

Throughout this course we’ll have you do a number of hands-on exercises to get familiar with accessibility topics and techniques. You can find all of the exercises in the project’s GitHub repo. Go ahead and clone it now so you can reference it when we get to the quiz nodes.

Note: We often shorten the word “accessibility” to “a11y” because there’s 11 letters between the “A” and “Y” in the word “Accessibility”. Sometimes you’ll see this pattern used in other contexts like i18n for “internationalization” and l10n for “localization”.

10.2 What is Accessibility

Even though we center our discussion of accessibility on users with impairments, we can all relate to the experience of using an interface, which is not accessible to us.

Have you ever tried to use a desktop optimized site on a mobile device, or seen, “This content is not available in your country.” when you are trying to watch a video online?

So in a broad sense you’ve almost certainly experienced being unable to access something. As we mentioned, this cause is largely concerned with accessibility in the narrowest sense of ensuring users with disabilities can access content.

However, addressing accessibility issues in the narrow sense very often improves the user experience for everyone.

To see where that’s true, let’s look at an example with some accessibility issues.

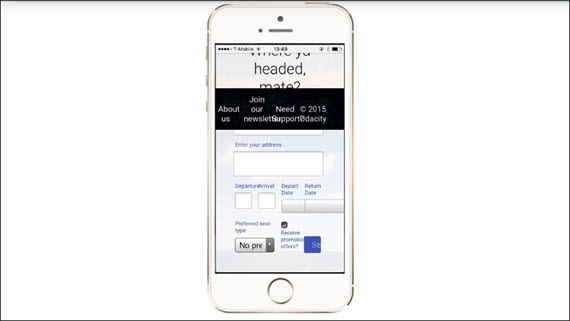

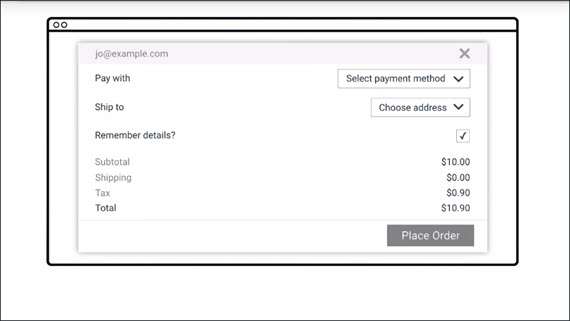

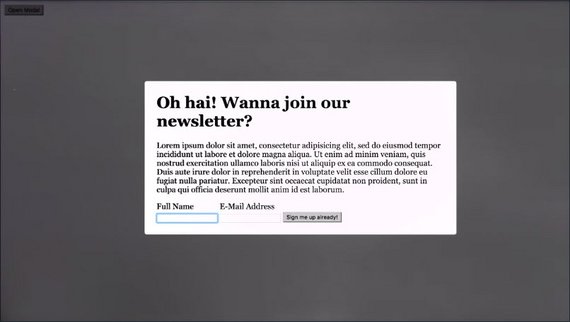

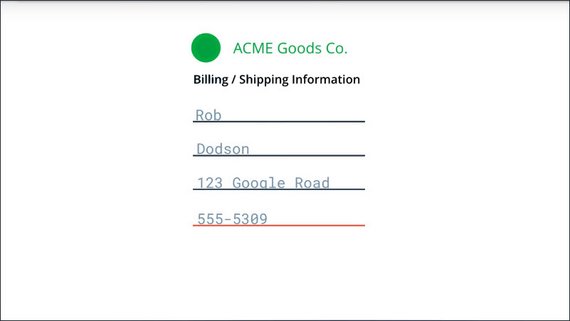

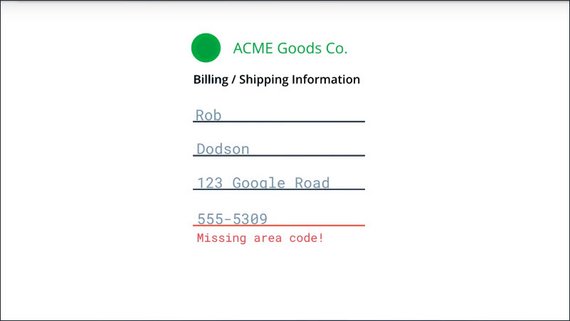

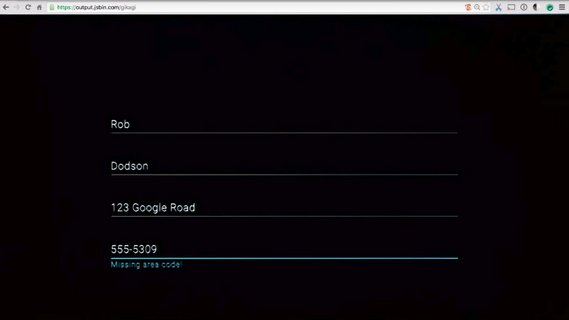

This form has several issues.

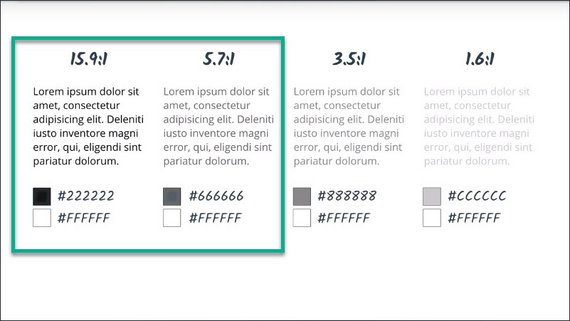

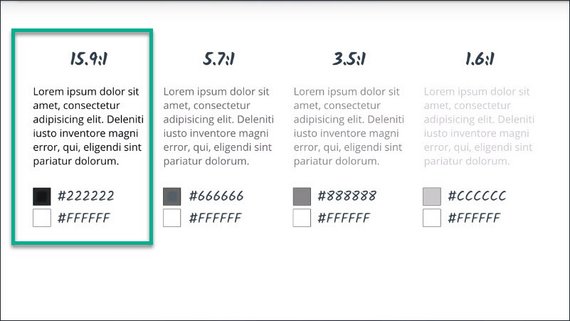

- The user name text and some of the text in the price details is low contrast. So that’s hard for low vision users to read.

- Having the form labels on the left and the form fields on the right, makes it hard for most people to associate them and almost impossible for someone who needs to zoom in to use the page.

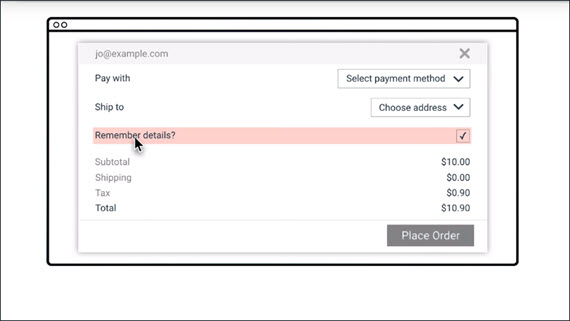

- The label isn’t correctly associated with the check box. So I have to tap or click the tiny square, rather than being able to click the label. Plus, a screen reader user would have difficulty figuring out the association.

So now let’s wave our accessibility wand and see with those issues fixed.

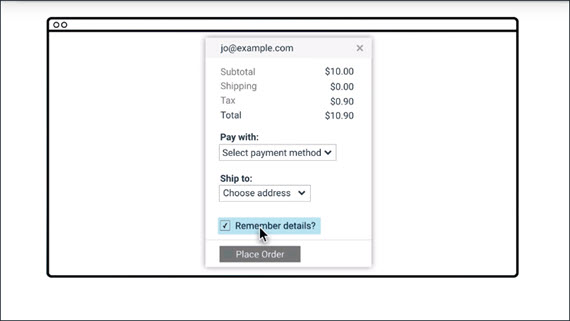

Here are the changes.

- We’ve made that low contrast text darker.

- We’ve modified the design so the labels are right next to things they’re labeling.

- We fixed that label to be associated with the check box. So now I can check and uncheck it by clicking anywhere on the label.

I’m much more comfortable actually using the accessible version. Sure, I could probably get by with the old version but it would cause some extra stress and possibly cause me to make mistakes if I was in a hurry or distracted.

True story, I once accidentally had something shipped to me in San Francisco instead of my parents in Australia, because of a form that looked a lot like the previous one we just saw. So, while we want to address accessibility first and foremost to avoid excluding people from accessing things, it certainly isn’t a zero sum game. We’re more likely to make things better for everyone by addressing accessibility.

10.3 Diversity of Users

Hi, my name is Victor Tsaran and I work as a technology program manager at Google. At Google I work on making sure that the products we create are accessible to the audience of our diverse users, regardless of their ability or impairment.

Modern web technologies make it very easy for a developer to create a website that’s difficult for someone who is blind to use.

If a user has no vision, it’s quite likely they would be using a screen reader, which is software that allows them to hear the information displayed on the screen via a text to speech synthesizer.

They may also be using Braille which allows them to feel the on-screen text with their fingers when using braille display.

Many websites are visual in their nature and lack keyboard navigation which is essential for blind people to be able to navigate through the content.

In general, it is safe to assume that there are more people with visual impairments, that is people who have some sight, as opposed to people who are completely blind. There are also people with low visual acuity and they may be using large print text or magnification when using the computer.

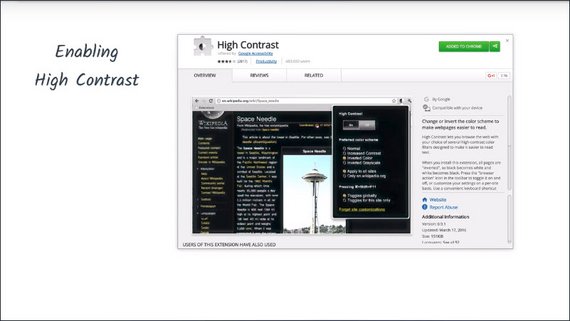

For example, my friend Laura uses magnification with text to speech, as well as various color contrast options.

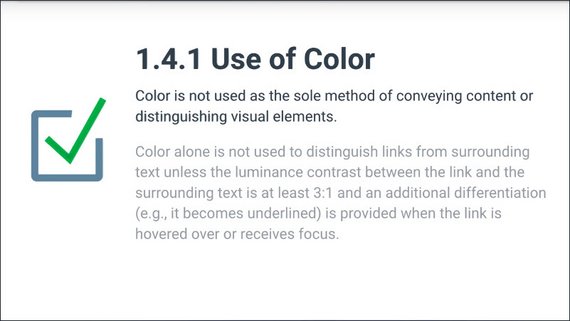

There are also people with poor color vision who may have difficulty distinguishing red and green or blue and yellow. This accounts for 9% of male and 1% of female.

We may also find ourselves with temporary challenges, such as when trying to use a computer in the sun or looking at a dodgy projector.

Whenever accessibility comes up in a conversation, people tend to picture someone who is blind like myself but there actually more impairments to think about and consider.

There is a huge number of people with motor or dexterity impairments. Such users may be using only the keyboard, head, or eye tracking software, switches, voice dictation etc. Someone may have a broken wrist, broken track pad, or simply riding the Shaker train.

By catering to users with permanent dexterity impairments, we ensure a great experience for everyone.

There are also users with hearing impairments. For example, some may be completely deaf, yet others have some hearing. The content that uses sound should provide some kind of visual alternative. For example, a messenger app could be using a flashing alert as well as sound notifications.

There are also users with cognitive impairments, for example ADD, dyslexia or autism. These users may require diverse accommodations, such as zooming the screen to make it easier to read the content, or minimal design to minimize destruction and cognitive load.

We can all probably relate to feeling stressful or cognitive load. So improving the experience for users with cognitive impairments makes it so much better experience for everybody else.

In summary, accessibility is really about making sure that the content and the websites we create is usable to people with various impairments or abilities.

Statistics

Some statistics on disability for the US:

- Around 2% of the population has some kind of vision disability (i.e. are blind or have significant difficulty seeing even with glasses)

- Around 50% of the population has some kind of clinically significant refractive error (a visual impairment which may be corrected with glasses if mild enough)

- Around 8% of males and 0.5% of females have some form of color vision deficiency

- Around 2% of adults have a hearing disability

- Over 4% have a cognitive disability (difficulty remembering, concentrating, or making decisions)

Sources

- Disability Compendium

- “The Perception of Color”

- “Prevalence of Refractive Error in the United States, 1999-2004”

10.4 Quiz: Broken Arm

Question 1 of 2

Which categories does the impairment broken arm fit into? (check all that apply)

- Visual

- Motor

- Hearing

- Cognitive

Question 2 of 2

Which temporalities does the impairment broken arm fit into? (check all that apply)

- Temporary

- Permanent

- Situational

10.5 Quiz: Blindness

Question 1 of 2

Which categories does the impairment blindness fit into? (check all that apply)

- Visual

- Motor

- Hearing

- Cognitive

Question 2 of 2

Which temporalities does the impairment blindness fit into? (check all that apply)

- Temporary

- Permanent

- Situational

10.6 Quiz: Audio

Question 1 of 2

Which categories does the impairment don’t, or can’t, listen to audio in an open office floor plan fit into? (check all that apply)

- Visual

- Motor

- Hearing

- Cognitive

Question 2 of 2

Which temporalities does the impairment don’t, or can’t, listen to audio in an open office floor plan fit into? (check all that apply)

- Temporary

- Permanent

- Situational

10.7 Quiz: Baby

Question 1 of 2

Which categories does the impairment holding a baby in one arm fit into? (check all that apply)

- Visual

- Motor

- Hearing

- Cognitive

Question 2 of 2

Which temporalities does the impairment holding a baby in one arm fit into? (check all that apply)

- Temporary

- Permanent

- Situational

10.7 Quiz: Concussion

Question 1 of 2

Which categories does the impairment concussion fit into? (check all that apply)

- Visual

- Motor

- Hearing

- Cognitive

Question 2 of 2

Which temporalities does the impairment concussion fit into? (check all that apply)

- Temporary

- Permanent

- Situational

10.8 Quiz: Repetitive Strain Injury

Question 1 of 2

Which categories does the impairment Repetitive Strain Injury (RSI) fit into? (check all that apply)

- Visual

- Motor

- Hearing

- Cognitive

Question 2 of 2

Which temporalities does the impairment Repetitive Strain Injury (RSI) fit into? (check all that apply)

- Temporary

- Permanent

- Situational

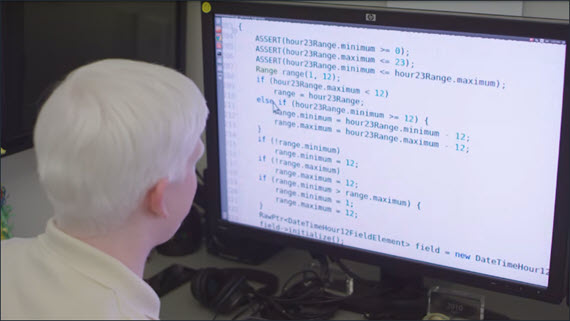

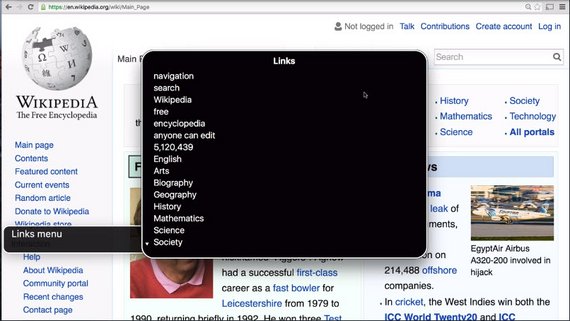

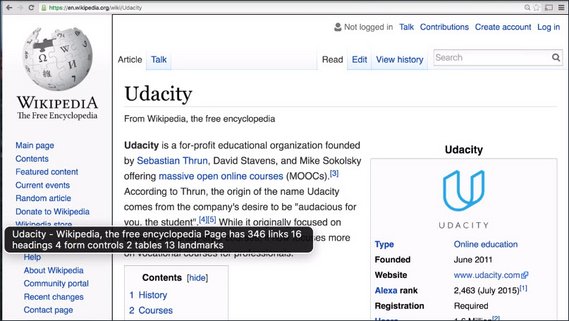

10.10 Using a Screen Reader

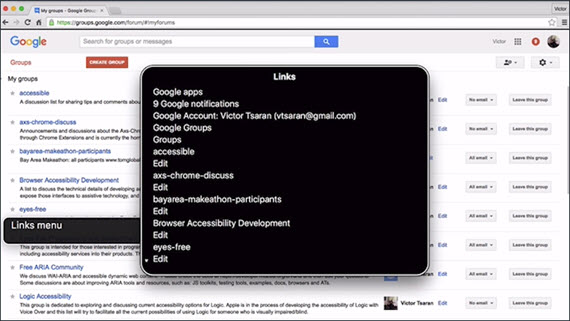

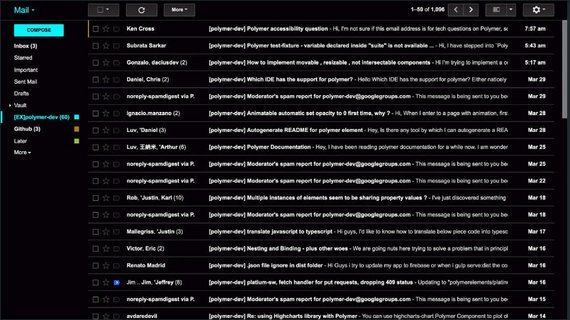

Hi, this is Victor again and this time I’d like to show you how I use a screen reader on everyday basis. In this particular case I will be using one of my daily things and that is looking at a public forum that talks about accessibility issues for the Android operating system.

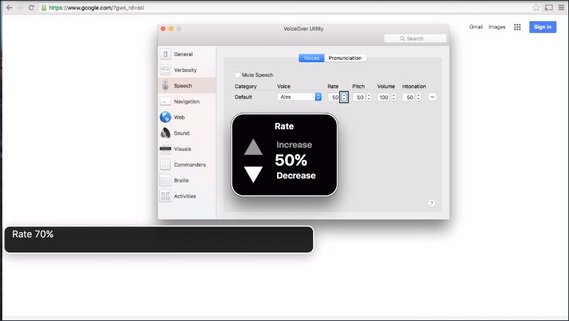

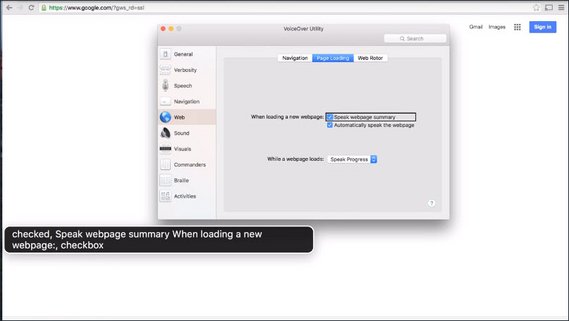

You will notice that my screen reader speaks really fast. As a beginner user you tend to listen at much lower speeds but as you gain efficiency with the screen reader, you will find that making it speak faster improves efficiency when browsing content on websites.

So back to my public form.I’m going to go to groups website.

Since I use this website every day I know that it provides a lot of shortcut keys that allows me to browse this website much faster.

So first I’ll go to my groups. And now I will be using a screen reader functionality there allows me to browse through the links on this webpage because I’d like to find a specific public forum I’m looking for.

Here you will see I have a few message threads and quite recently I heard about this new app called Swift. It’s a braille Keyboard that allows people who are blind to type braille faster on Android.

So I’m going to go back to this thread and look at some of the messages that I may have missed. Looking at messages that I included in this thread. I used again, shortcut keys to quickly move through messages. If there is anything new since the last time I looked at this forum. Yeah, there’s quite a bit to read.

Anyway I hope this gives you a quick glance into how I use this view to an everyday basis.

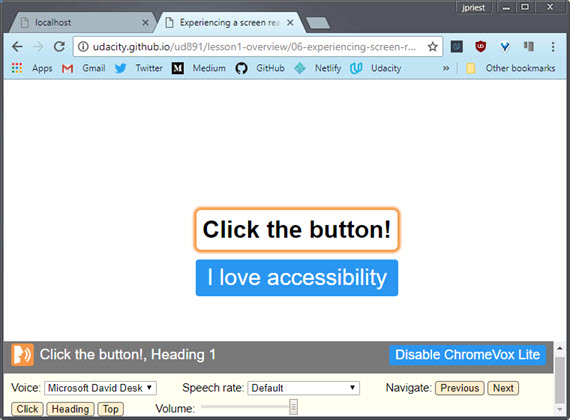

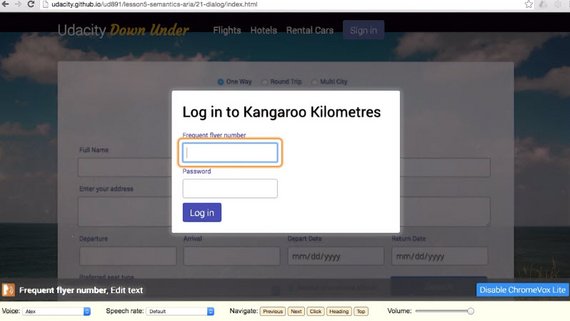

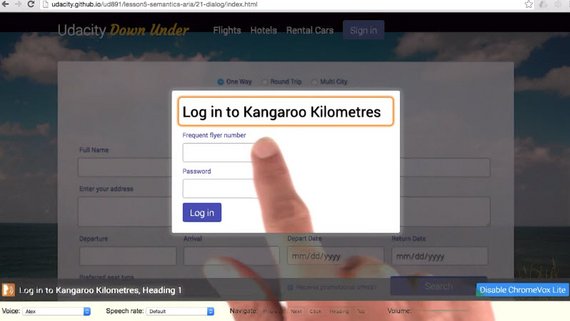

10.11 Quiz: Experiencing a Screen Reader

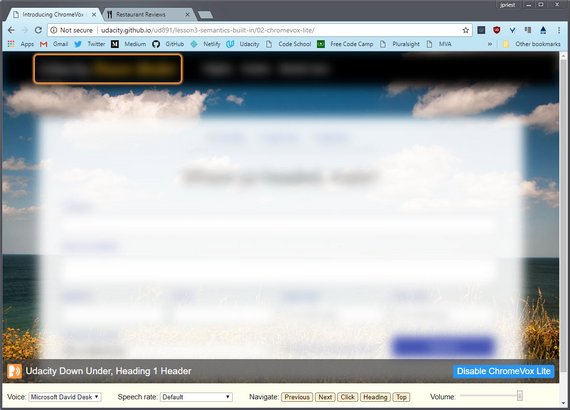

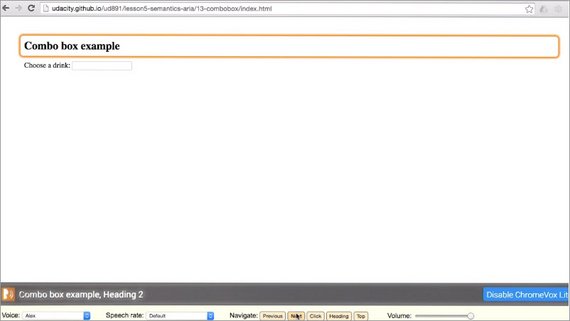

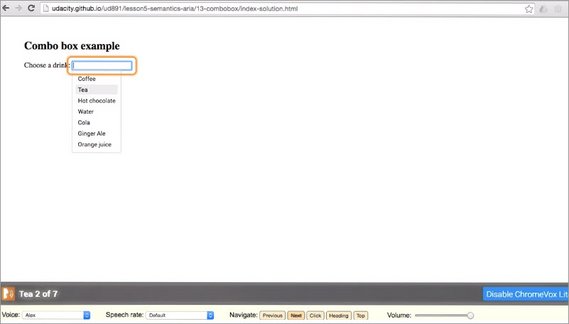

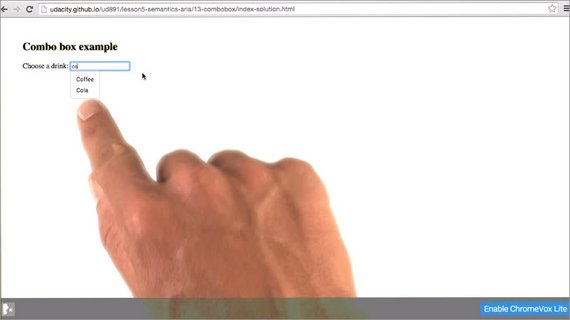

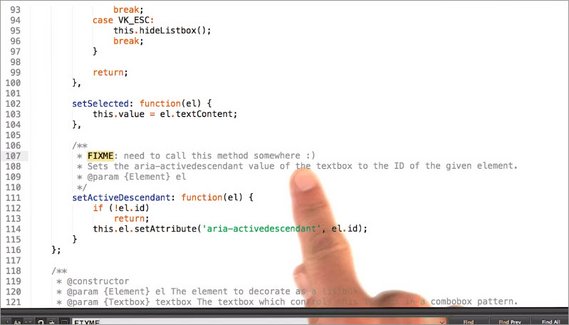

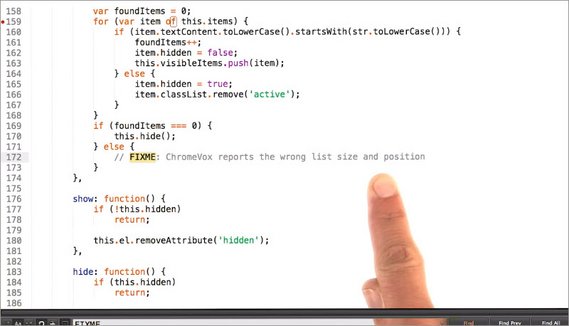

Alright, it’s time to start working with a screen reader. Head over to this sample page and click the ‘Enable ChromeVox Lite’ button to get started. When you’re finished, come back here and enter the secret word.

Important: To navigate with ChromeVox Lite you will need to use the buttons at the bottom of the screen. If you try to just click on the button with your mouse the page will lose focus and you’ll have to refresh and start over. So… no cheating! “ChromeVox Lite” is a modified version of ChromeVox which is injected into some of the pages used in this course. Using ChromeVox Lite is optional for all exercises - the examples should will work just as well with the ChromeVox extension, or any other screen reader you may already be familiar with. If you do choose to use ChromeVox Lite, it’s very simple:

- Enable ChromeVox Lite via the “Enable ChromeVox Lite” button in the bottom right hand corner of the screen, or via the other “Enable ChromeVox Lite” button which appears if you press

TABonce. - The controls for ChromeVox Lite will appear once it is enabled:

- The “Voice” drop-down allows you to choose alternate voices

- The “Speech rate” drop-down allows you to make the speech faster or slower (if you find yourself getting bored waiting for ChromeVox to finish what it’s saying, try speeding it up!)

- The “Navigate” buttons allow you to move ChromeVox’s focus to non-focusable items on the page, such as headers

- Finally, the volume control allows you to fine-tune ChromeVox’s volume.

10.12 Checklists

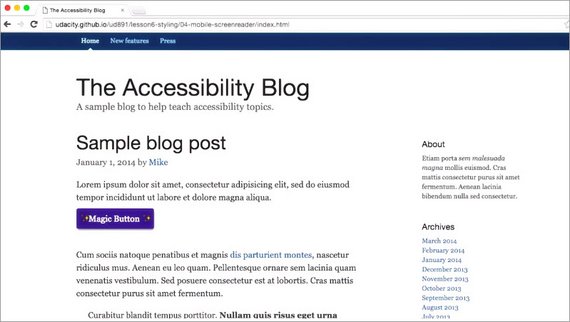

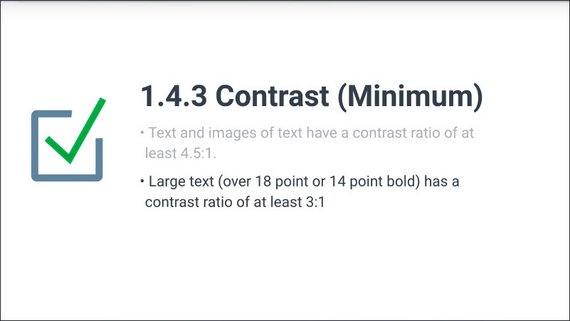

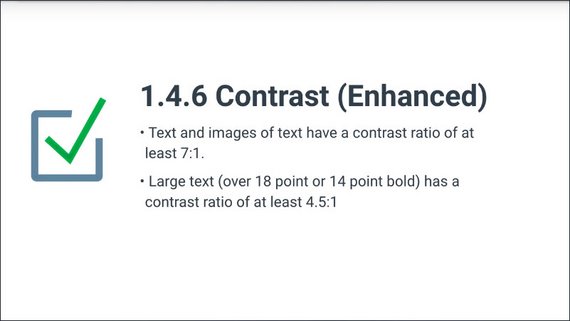

Because accessibility is so broad and the usership is so diverse, we’re going to need a roadmap to guide us on our journey. Throughout this course we’ll be referring to WCAG, or the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines 2.0.

WCAG is a set of guidelines and best practices which have been put together by accessibility experts to try and answer the question of what accessibility means in a methodical way.

Several countries actually mandate the use of these guidelines in their web accessibility legal requirements.

WCAG is organized around four core principles.

- Perceivable - The first is making sure users can perceive content. This helps us keep in mind that just because something is perceivable with one sense such as sight, that doesn’t mean that all users can perceive it.

- Operable - Second, is it operable? Can users use UI components and navigate the content? For example something which requires a hover interaction cannot be operated by someone who can’t use a mouse or is using a touchscreen.

- Understandable - Third, can users understand the content? Also, can all users understand the interface and is it consistent enough to avoid confusion?

- Robust - Is it robust enough for the content to be consumed by a wide variety of user agents and does it work with assistive technology?

Together this forms POUR.

While WCAG provides an extremely comprehensive set of guidelines to help us keep many facets of accessibility in mind, it can also be a bit overwhelming. To help mitigate this, the WebAIM group has distilled the WCAG guidelines down into an easy to follow checklist, targeted specifically for web content.

The webbing checklist can give you a short high level summary of what you need to implement while also linking to the underlying or tag specifications if you need an expanded definition.

Both WCAG and the checklist cover a lot of the accessibility space.The guidelines can only ever be a limited proxy for actual accessibility. What actually matters is the user experience, not just checking some box.

So while these guidelines give us a framework for thinking about accessibility, there may be places where they’re incomplete or even give advice which is a little out of date. However, they’re still an excellent resource for helping us integrate accessibility into our process.

With these tools in hand we can chart a direction for our accessibility work and be confident that, so long as our project is meeting the outlined criteria, our users should have a positive experience.

Resources

10.13 Quiz: Using WebAIM Checklist

Using the WebAIM Checklist for WCAG 2.0, find the matching rule that dictates “the web page has a descriptive and informative page title.”

- Rule: 2.4.2

- Section: Operable

10.14 Course Practicalities

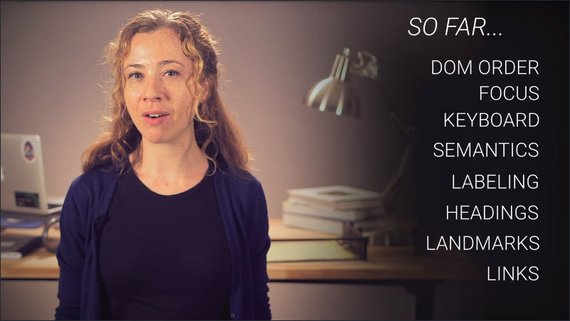

- We’ve heard a lot about what accessibility is and why it matters for everyone

- We heard about some different types of impairments and what we might need to think about

- We saw what it’s like to use a screen reader

- We took a quick look at WCAG and the WebAIM accessibility checklist

For the rest of the course we’re going to dive into the practicalities of actually creating accessible websites. We’re not going to just talk at you for the whole course, you’re going to actually create some accessible code

We’re going to organize this around three main topics

- Focus and keyboard which looking at how to make sure that we build things which can be operated with a keyboard. This is important for users with motor impairments but also ensures that your UI is in a good shape for the next topic which is semantics.

- Semantics is where we make sure that we’re expressing our interface in a robust way which works with a variety of assistive technology.And finally

- Styling and visual design. We’ll look at some techniques for making sure the visual UI is as flexible and usable as possible.

Now each of those topics could probably fill a whole course by themselves. So we’re not going to be able to cover every single aspect of creating accessible websites. However, we’re going to give you enough information to get started and point you at some good places to learn more about each topic.

I’m sure you’re all eager to get started so let’s begin with a look at how and why you need to think about focus in your web application.

Lesson 11. Focus

11.1 Intro to Focus

In this lesson I’ll be talking about focus and how you can manage it in your application.

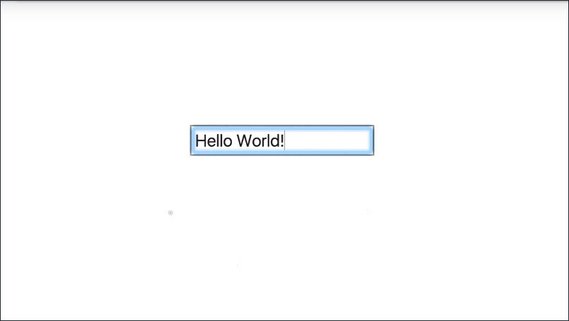

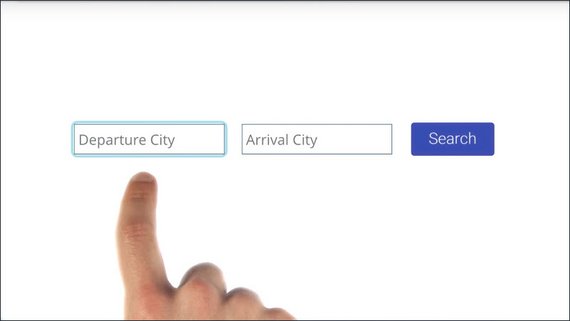

Now in a nutshell, focus refers to the control on the computer screen that receives input from the keyboard and from the clipboard when you paste.

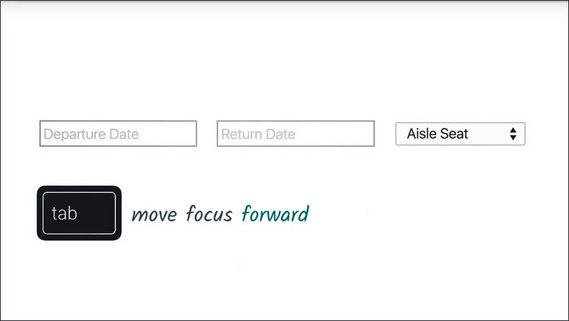

You’re probably familiar with focus for text fields. In order to type in a text field you first have to go over with your mouse and click on it. Well that act of clicking on the text field, that’s actually what focuses it. You may also know that if you then press the [tab] key it will then move focus to the next text field or available control.

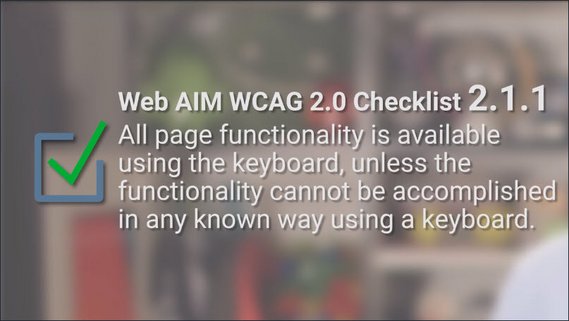

Now some users drive the computer entirely with the keyboard or some other type of discrete input device. For those users, focus is absolutely critical. It’s their primary means of reaching everything on the screen. And so for that reason the Web AIM checklist states in section 2.1.1, that all page functionality should be available using the keyboard, unless it’s something you couldn’t normally do with a keyboard like freehand drawing or something like that.

So this is a great place to start learning about accessibility because obviously we all know how to use a keyboard. It’s very easy to relate to and test, and it benefits virtually all of our users.

There’s users out there with motor impairments which could be caused by anything from paralysis or even just a broken arm. Those folks may be relying on a keyboard or switch device to navigate your page, so a good focus strategy is going to be absolutely critical for them.

For the power users out there, those folks who know every keyboard shortcut on their machine and hate having to use the mouse, well, for them, being able to navigate, for instance, a form on your site, is just going to make them more productive.

So well-implemented focus strategy means everyone using your application will have a better experience. And as we’ll see in the next few lessons, the work that we do today on focus is actually an important primer for supporting assistive technology users.

WebAIM checklist item

11.2 What is Focus

As you learned in the previous lesson, focus determines where keyboard events go in the page.

To give you an example, if I go over and focus this text input field using my mouse and then begin typing, the input receives the keyboard events and displays the characters as I’ve typed them.

The currently focused item is often indicated by a focus ring, where the actual styling of that ring depends on the browser and any additional styling that the page author may have applied.

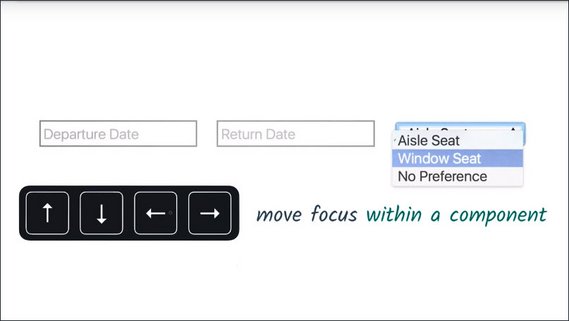

As a user,you can control which element is currently focused using your keyboard. Pressing the Tab key will move focus forward through the document.

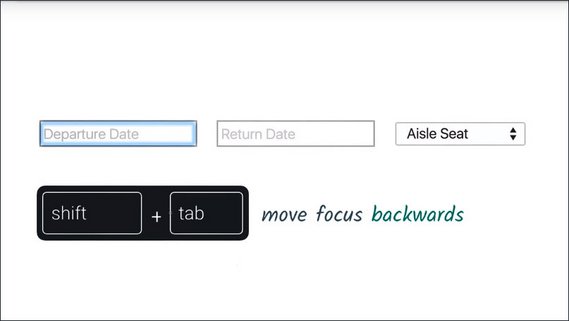

Shift+Tab moves focus backwards.

And you can use the arrow keys to move focus around within a component.

On MacOS X, this works a little differently. While Chrome will always let you navigate with Tab, you’ll need to press Option+Tab in order to change focus in other browsers like Safari.

If you like, you can change this by going to your System Preferences, going to the Keyboard section, clicking on the Shortcuts tab and then changing this radio group to say All controls.

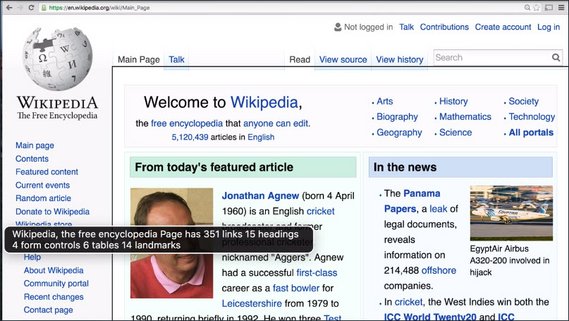

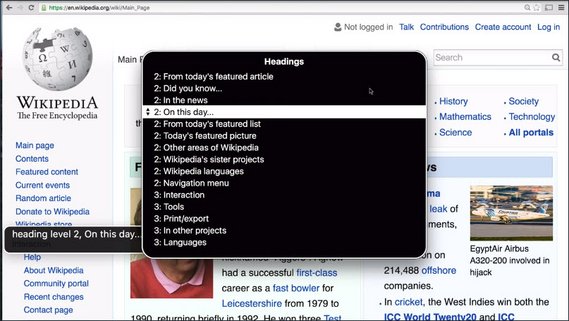

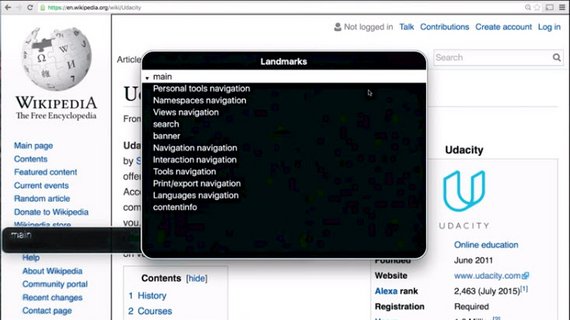

To give you an example of focus in the real world, here I am on Wikipedia, and as I press the Tab key, the browser is going to navigate through all of the focusable elements on the page.

Eventually I’ll reach a stopping point and hit Shift+Tab and now I’m moving backwards through the page. This ordering is called, creatively enough, the tab order.

Making sure your application has a logical tab order is an important step, which we’re going to cover later on in this course.

Now built-in interactive HTML elements like input, button, and select are all implicitly focusable. Meaning that they’re automatically inserted in the tab order and that they also have built-in keyboard event handling.

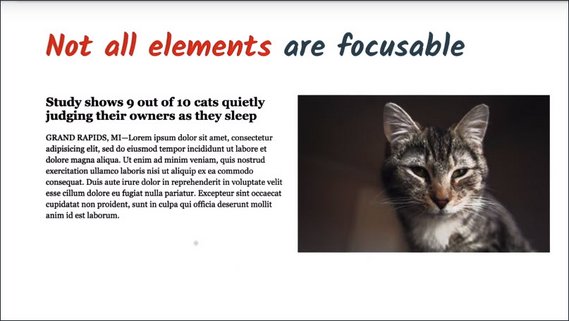

But not all elements are focusable.

This header, the paragraph below it, and this image are not focusable, and they’re not implicitly inserted in the tab order. That’s by design.There’s generally no need to focus something ifa user can’t interact with it or provide it some sort of input.

Notes

Move focus around the page using your keyboard:

TABwill move focus forwardSHIFT - TABwill move focus backwardsArrow keyscan be used to navigate inside of a component

https://www.w3.org/TR/html5/editing.html#focus-management

11.3 Quiz: Experience Focus

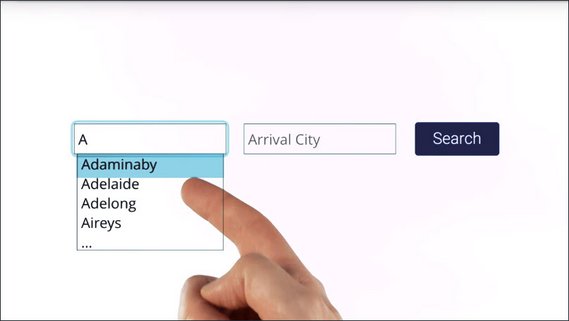

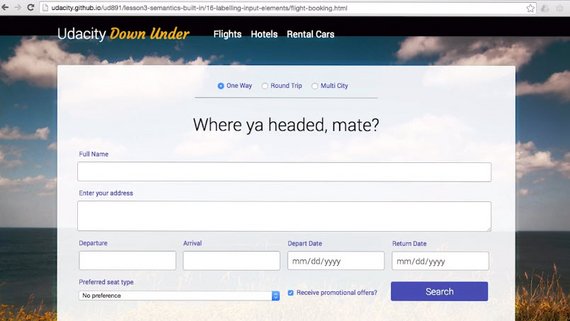

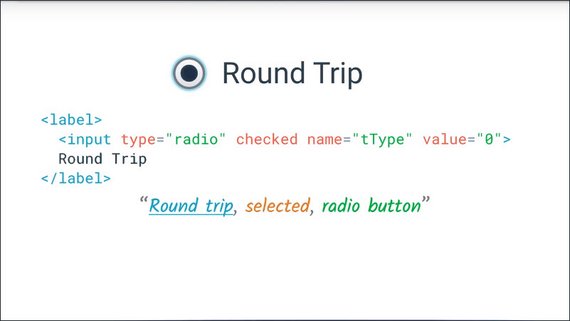

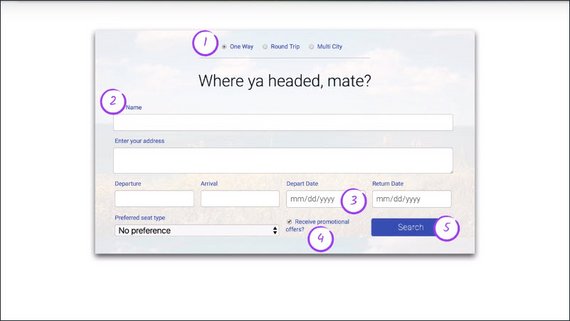

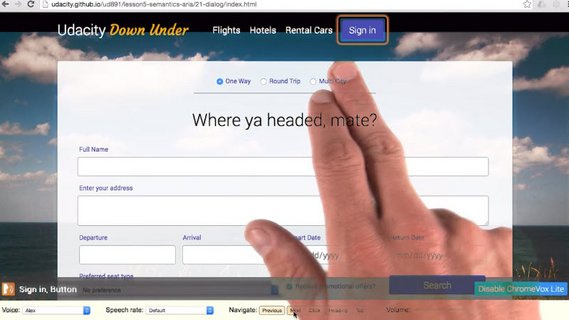

Let’s try out some of the focus techniques discussed in the previous lesson. I’d like you to search for a ticket on Udacity’s new Australian airline website using your keyboard.

We’ve disabled the mouse on this page, so you can’t cheat. I’d like for you to search for a ticket that is a round trip to Melbourne leaving on 10/12/2017 returning on 10/23/2017, is a window seat, and you do not want to receive any promotional offers.

Quiz

Try out our flight booking form using only your keyboard. You’ll need to search for a ticket that matches the following criteria:

The ticket should…

- Be a round trip

- to Melbourne

- leaving on 10/12/2017

- returning on 10/23/2017

- window seat

- and you DO NOT want to receive promotional offers 😀

If you’ve filled out the form correctly then pressing the Search button should give you a notification that you’ve passed.

Remember

TABwill move focus forward to the next elementSHIFT - TABwill move focus backwards to the previous elementArrow Keyscan be used to move focus within an element

11.4 DOM Order Matters

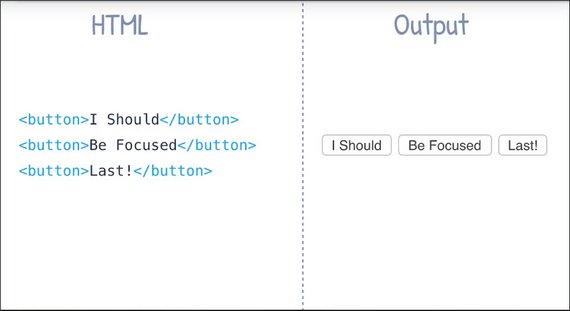

So working with native elements is great for focus behavior, because they’re automatically inserted into the tab order based on their position in the DOM.

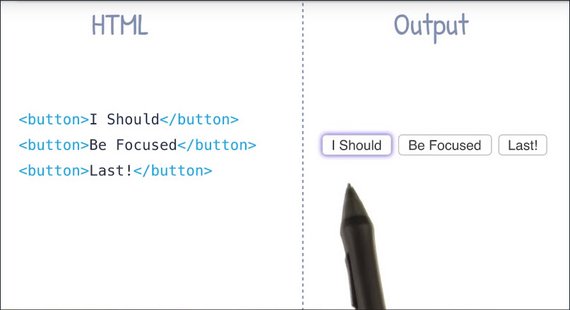

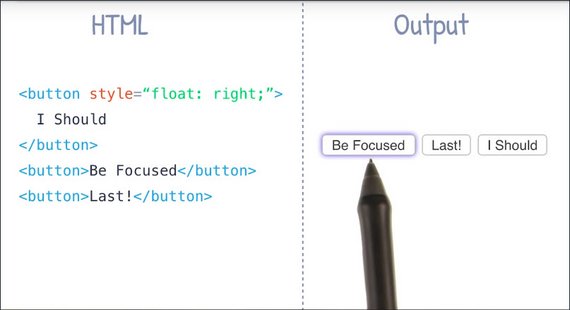

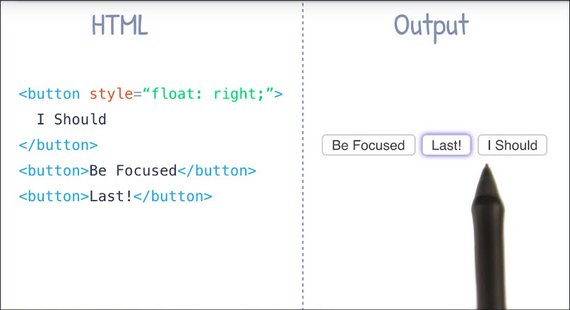

To give you an example I’ve written a little bit of HTML here.

I’ve got three button elements and then you can see the output over here on the right. So there’s three button elements rendering inside of my browser.

Now because the tab order corresponds to the DOM order, when I go and press the tab key you’ll see that the first button element gets the focus indicator around it.

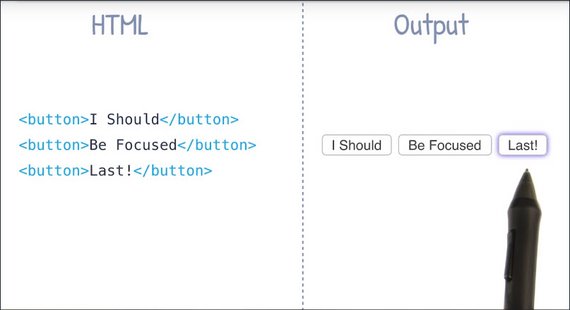

And as I keep pressing tab, you’ll see the next item in the DOM order gets focused and tab again, now the last item in the DOM order is focused.

Now it’s important note that using something like CSS, it’s possible to have things appear in one order on screen, but actually exist in a different order over in the DOM.

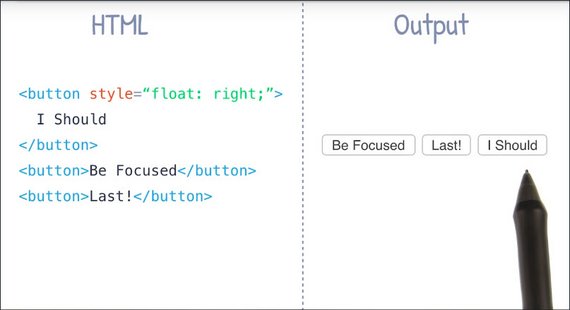

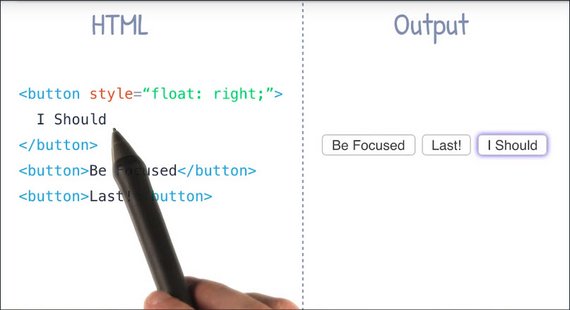

To give you an example of that, what I’ve done now is I’ve just added this inline style to my first button element and I’m telling it that I want to float to the right.

Now what this is going to do is it’s going to visually change the ordering of these buttons here such that our first DOM element is now appearing last on screen visually. So even though the visual order has changed, the DOM order remains the same.

Let’s see how that effects tabbing. When I press the tab key, the first DOM element is still focused, but now visually it’s the last element in this group which is kind of weird.

If I press tab again, now we see that the second DOM element, which is the first visual element becomes focused.

And pressing tab again, I’ve got this middle element now being focused, even though that’s the last DOM item.

So the moral of the story is, be careful when you’re using something like CSS to visually change the position of your elements on screen. This can cause the tab order to jump around seemingly at random and for users relying on a keyboard this can be extremely confusing.

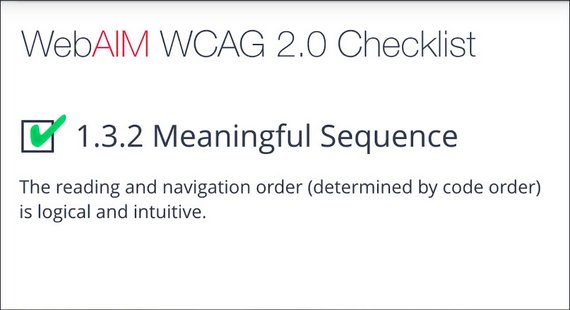

For this reason the WebAIM checklist specifically states in section 1.3.2 that the reading and navigation order as determined by code order should be logical and intuitive in your application.

I have just sort of a general rule of thumb. I like to tab through my page every so often just to make sure I haven’t accidentally messed up the tab order. It’s a good habit to adopt and it’s one that doesn’t really require a ton of effort on my part.

11.5 Quiz: Fixing DOM Order

Here’s a page with a busted tab order.

Go ahead try to navigate this page using the keyboard only you’ll find you skip around a lot. It would be much easier if we navigated in this order.

- Navigation links

- Search

- Content links

- Footer.

Using a text editor, see if you can fix the order of the elements in the DOM, so that the tab order makes sense.

Quiz

This exercise can be found in the folder lesson2-focus/02-dom-order within this course’s GitHub Repository.

Tabbing around the page should reveal a mixed up tab order. Read through the index.html and see if there are any places where elements may be in the wrong order. If something looks out of place see if you can fix it so the tab order works as expected. If you get stuck you can refer to the solution directory.

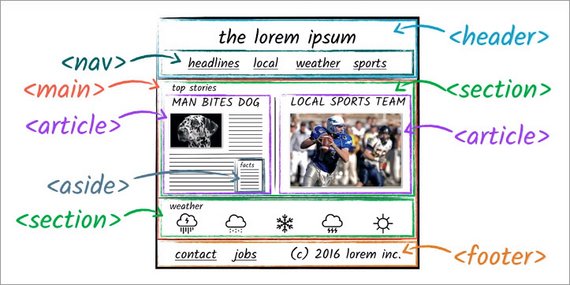

Solution

Looking at the markup for the page, I can see that the search link is actually higher in the DOM order than the other links. It’s using a pull-right class to float over to one side.

The easiest thing to do is to just move the search button below the other elements. That will give the same visual presentation but now the tab order makes sense.

I also noticed that the newsletter is jumping ahead of the other elements on the page because it’s absolutely positioned to appear at the bottom of the page. Just like the search link, I’ll move the newsletter down to the bottom of the document just after the main element.

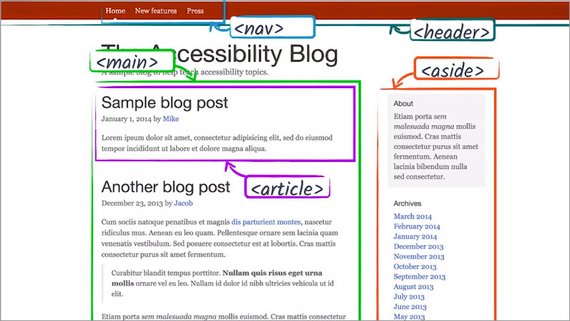

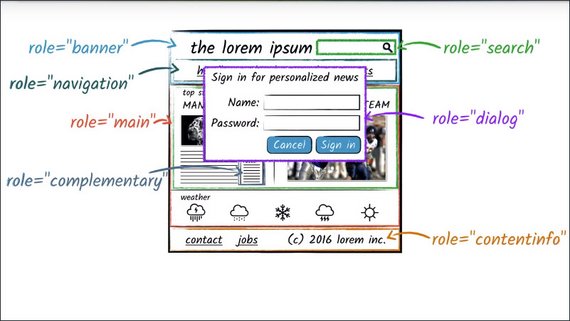

Now is also a good time to improve our semantics a little bit. Instead of just using a div for this element, I can replace it with a footer tag. Doing so can benefit screen readers who rely on these kind of landmarked elements to navigate the page. It’s also a little more concise than div class equals footer.

I’ll talk more about semantics and navigation in a future lesson.

11.6 Using Tabindex

Because native elements are automatically inserted in the tab order, they can be very convenient to use. But there are instances when you’ll want to modify the tab order.

Like if you’re building a component without a native analog, like this dropdown up here,

or if you need to have something off screen that should only be focusable when it appears, like perhaps a modal window.

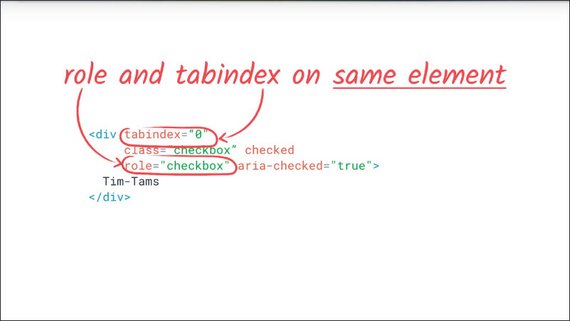

For these cases, you can use the tabindex attribute.

Tabindex can be applied to any HTML element, and it takes a range of numeric values.

<div tabindex="0">Focus Me!</div>

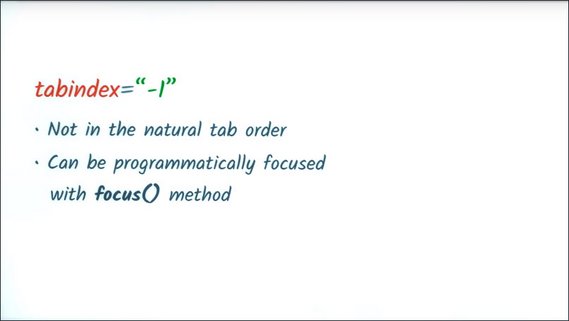

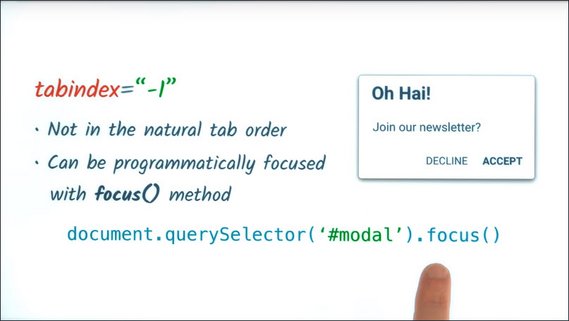

A tabindex of -1 means that the element will not be in the tab order, but it can be programmatically focused via JavaScript, by calling the element’s focus method.

This can be especially useful for off screen content which appears on screen in response to a user event. When the new content is displayed, you may wish to call its focus method which will then direct future keyboard events to it.

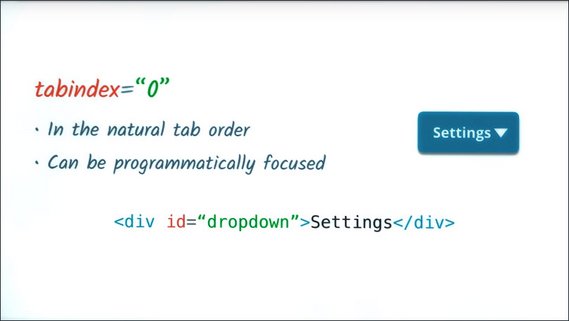

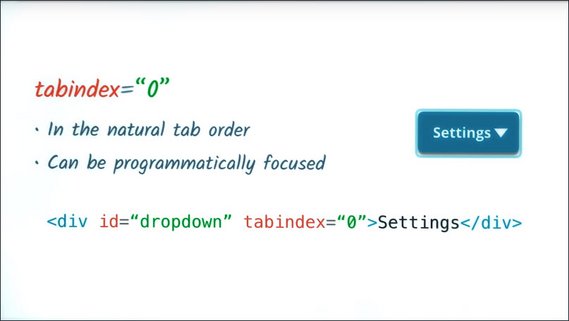

A tabindex of 0 will add the element to the natural tab order, plus, that element will also be focusable by calling its focus method.

For example, here I’ve got a fancy button that I’ve created out of just a div.

Now, without a tabindex attribute, if I press the Tab key, this element will not receive focus.

By adding a tabindex of zero, now when I press the Tab key, this element gets focused, and future keyboard events get directed to it.

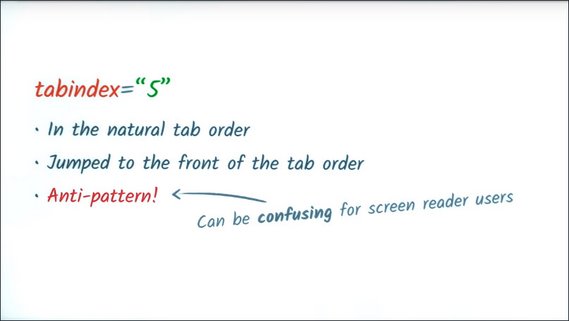

A tabindex of greater than zero, for instance something like tab index of 5 will jump the element to the front of the tab order regardless of where it is in the DOM.

If there are multiple elements with a tabindex greater than zero, the order will start from the lowest value that is greater than zero and then work its way up.

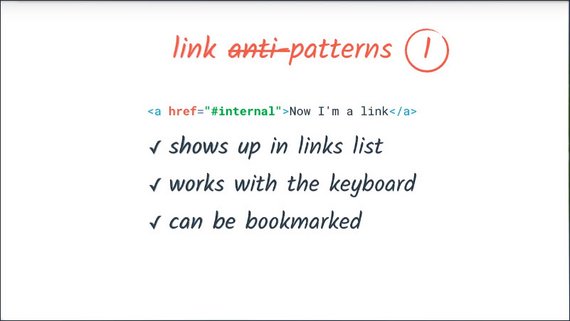

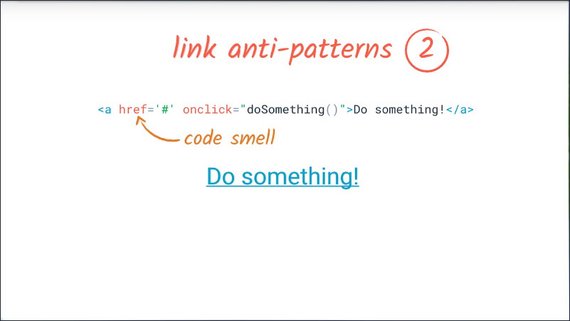

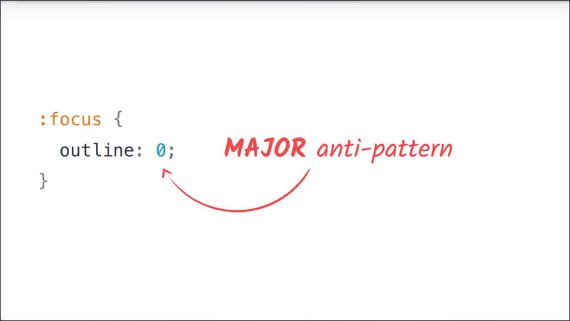

In general, using a tabindex greater than zero is discouraged and considered a bit of an anti-pattern.

If you get in the habit of using it, you can quickly end up with a very jumbled tab order, and it can make things especially confusing for screen reader users who navigate the DOM in a linear fashion.

Ideally, if you need to put something earlier in the tab order, the best bet is to move it up in the DOM.

11.7 Deciding whats in focus

It’s tempting, especially when you’re starting to look at screen reader accessibility, to add tabindex to seemingly important elements like headers, for instance, in order to help out the user.

That’s actually counterproductive. Normally, you only want to add focus behavior to interactive controls like buttons, tabs, drop downs, or anything that the user might provide input to.

If you’re worried about visually impaired users missing out on your content, don’t be. We’re going to show in the next few lessons how screen reader users explore non interactive content.

So when you’re adding a tabindex attribute, stop and ask yourself, is this something the user is going to interact with? If the answer is no, you almost certainly want to leave it alone with the exception of a few caveats which will cover in just a moment.

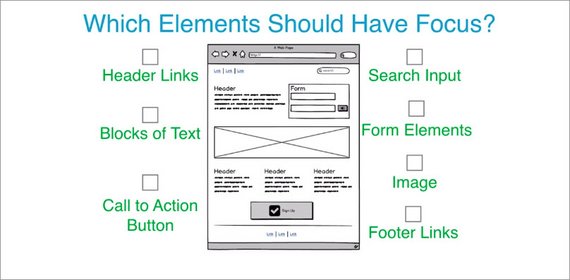

11.8 Quiz: Which Elements should have focus

Rob just told us that we should typically only add tabindex attributes to interactive elements and not our site content.

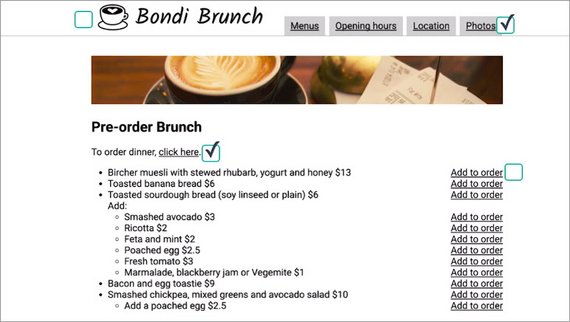

With that in mind, given the following page, check the box for any element which should be focusable. This could be an element that is natively focused or one that you might add a tab index to.

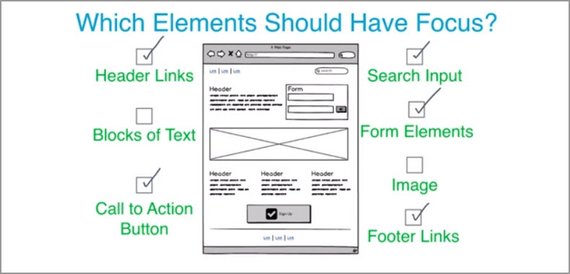

Solution

The following elements should have focus.

- Header links,

- Search fields,

- Form input fields

- Submit button

- Large Call to Action button

- Footer links.

I’m not going to add tabindex to any headings or the paragraphs of text. Even if that content seems super important, it’s not something the user can interact with, so there’s no reason to make it focusable.

Similarly, even if the big image is really awesome, there is no reason to make it focusable. Screen reader users will still be able to understand the content of the image, so long as we provide proper Alt tag support,which Alice will touch on in just a few lessons.

11.9 Managing Focus

I mentioned previously that you shouldn’t add tab index to site content as a general rule, but there is one exception and that’s when you’re manipulating the page in response to a user action.

A scenario might be that a user goes and clicks on one of these menu items and the page then does an animated scroll, down to that particular section.

Or, if you are building a single page web app, clicking on one of the navigation links changes the content of the page without doing a full page refresh.

In either of these situations, you’ll want to

- pick an appropriate header

- give the tabindex a negative one so it doesn’t appear in the natural tab order

- call its focus method after the user has taken their action.

This process is known as Managing Focus, and it’s an extremely important technique that keeps the user’s interactive context in sync with the visual representation of the site.

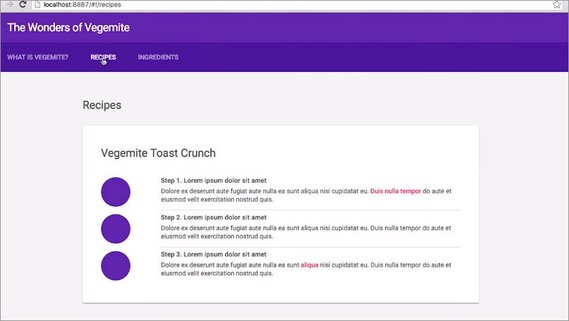

Let’s go through that single page app scenario I just discussed and I’ll highlight what happens when we don’t manage focus. And then demonstrate how the experience can be improved when we do manage focus.

Before

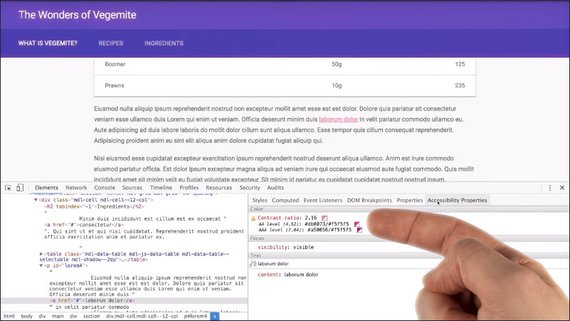

So here we are back at our site. I’m going to go click on the “What is Vegemite link?” link and when I do that I’m going to want to start clicking around some of the anchors in the main page content.

So using my keyboard, I’ll navigate over there. I’ll press enter and now I’d like to click the link in the body content, but in order to get there I’m going to have to tab back through my navigation.

Now, there’s only a few navigation items here so it’s not the biggest deal in the whole world. But you can imagine on a complex site with a lot of navigation, that it could be a lot of work to get through all of that.

Furthermore, as a screen reader user, I might not even know that the page content has loaded in and changed yet. I may just be sort of sitting around waiting for something to happen after I’ve clicked that link.

Let’s see if we can improve upon this a little bit.

After

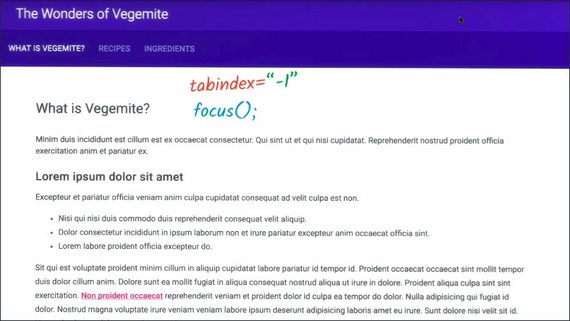

So what I’m going to do is, take the heading and I’m going to give it a tabindex of -1.

If you recall, that means the element won’t be in the tab order, but I can programmatically focus it using JavaScript.

Now, I can

- listen for my anchor clicks

- I can tell the page content to update

- I can call the focus method of that header.

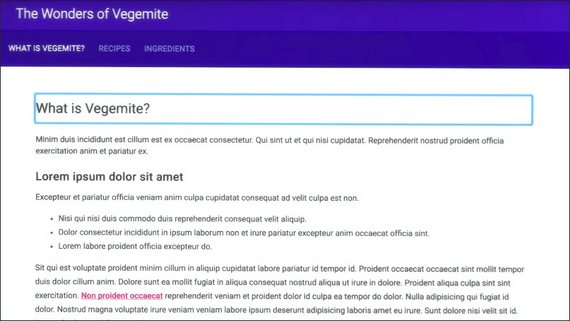

Once I’ve done that, the user will then be moved down in here, inside of our main page content, and then can then quickly Tab, or Shift+Tab to whatever they want.

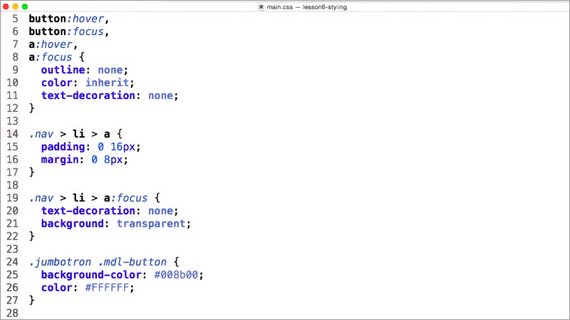

Now you might notice that as we do this, the header itself gets a large focus ring placed around it. I’m going to talk more about styling focus in a future lesson.

11.10 Quiz: Manage Focus Yourself

Here’s a classic single page web app where clicking a navigation item will change the page content.

Using your JavaScript skills make it so each heading is properly focused when the user clicks a navigation link.

Solution

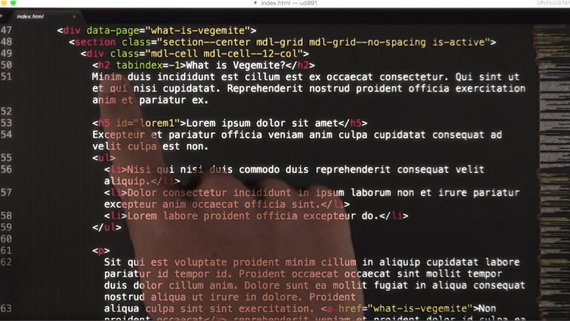

Inside each section of the page, I’m going to find an appropriate header like these h2s, and give it a tab index of negative 1.

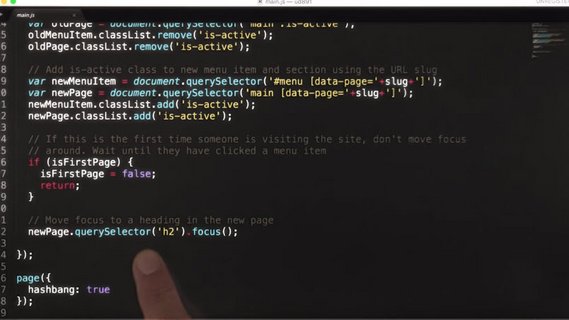

Next, I’ll open the router code in main.js.

When the page changes, I’ll look for a new header by calling newPage.querySelector h2 and its focus method. To prevent this code from running the first time the user visits the site, I’ll add a little guard variable called isFirstPage and set that to false after the first page runs.

var isFirstPage = true;

page('/:slug', function(context) {

// This will match any value after the first / in the url. For example, if

// the url was /foo, the value of slug would be "foo".

var slug = context.params.slug;

// Remove is-active class from previous menu item and section

var oldMenuItem = document.querySelector('#menu .is-active');

var oldPage = document.querySelector('main .is-active');

oldMenuItem.classList.remove('is-active');

oldPage.classList.remove('is-active');

// Add is-active class to new menu item and section using the URL slug

var newMenuItem = document.querySelector('#menu [data-page='+slug+']');

var newPage = document.querySelector('main [data-page='+slug+']');

newMenuItem.classList.add('is-active');

newPage.classList.add('is-active');

// if first visit then don't set focus to h2 element

if (isFirstPage) {

isFirstPage = false;

return;

}

// set focus to h2 in the new page

newPage.querySelector('h2').focus();

});

From then on, anytime we switch to a new page, our header focus code will run.

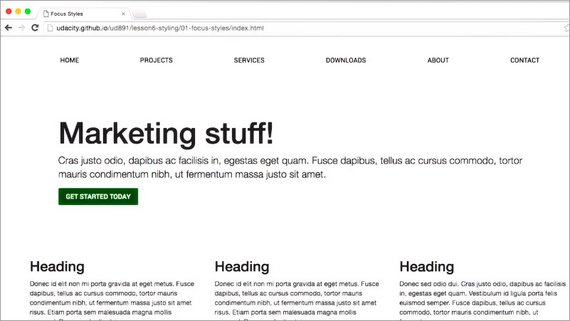

11.11 Skip Links

Since we’re on the subject of focus management, let me show you another really useful technique.

On most websites the main content is usually not the first thing in the DOM, instead we often begin with navigation, sublists, side bars, hamburger menus, and other bits of page scaffolding.

This means that keyboard and screen reader users must first navigate through all of this content before they can get at the actual heart of the page. For users with motor impairments this is especially frustrating.

A user who’s unable to move their arms might be navigating the page with a switch device, which they activate by tapping their head. This user is going to have to tap over and over again to get through all of these elements before they can get to our content, and that’s not cool.

Thankfully, there’s an easy to implement solution to this problem. Let’s create a hidden link that allows keyboard and switch device users the ability to jump straight to our page content. These links are often referred to as skip links.

Let me show you an example.

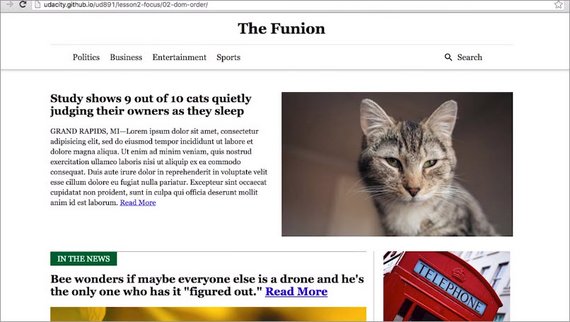

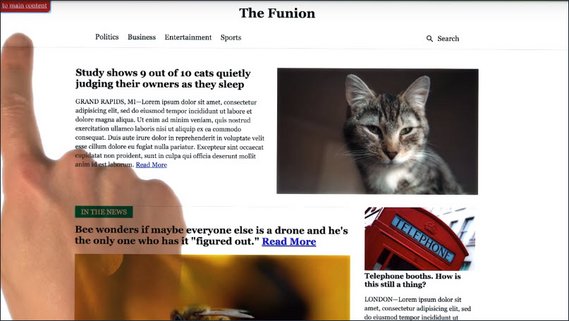

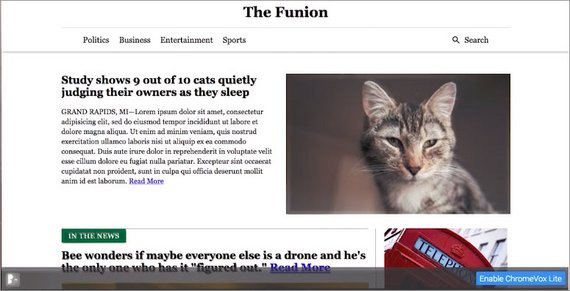

Here we are on the Funion news site. I have some navigation at the top which normally the keyboard user would have to tab through. Instead, when I press tab, the first thing I’m presented with is a little option up here in the top of the corner, which is asking if I’d like to skip down to the main content.

Pressing Enter will then move focus down to the main content area, bypassing all of our navigation.

Implementing a skip link is actually really easy. I’ll start by creating a named anchor. So the href of this anchor refers to the ID of another element that I’ll have on the page. I’m also going to give this element a class of skip-link so I can refer to it in CSS later.

<a href="#maincontent" class="skip-link">Skip to main content</a>

<nav>

...

</nav>

<main id="maincontent">

...

</main>

I want the skip link to appear early in the DOM, so I’m going to put it before my navigation. To connect my skip-link to my main content, I’ll give my main element an ID of maincontent, which matches the href value so the anchor and the main section are now connected.

In newer versions of Chrome and Firefox just doing this right here will allow you to move focus down to the main element when the skip-link is pressed. But for older browsers which don’t move focus when named anchors are clicked, I’m also going to want to add a tabindex -1.

<main id="maincontent" tabindex="-1">

...

</main>

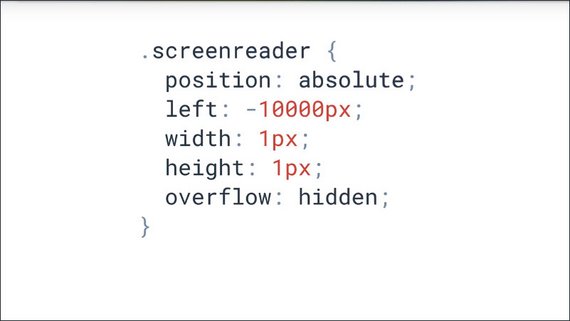

Over in my CSS, I’ll make sure that the skip-link has an absolute position, so it can appear in the top left corner of the screen. But I’m going to make it initially positioned off screen by setting the top value to -40 pixels.

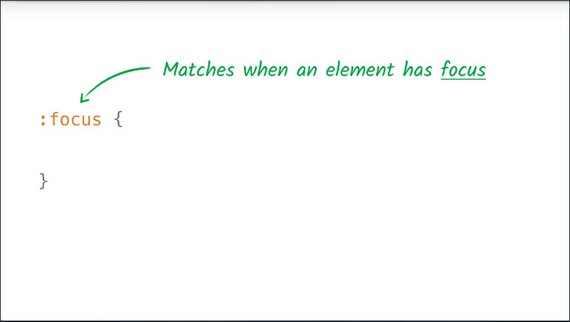

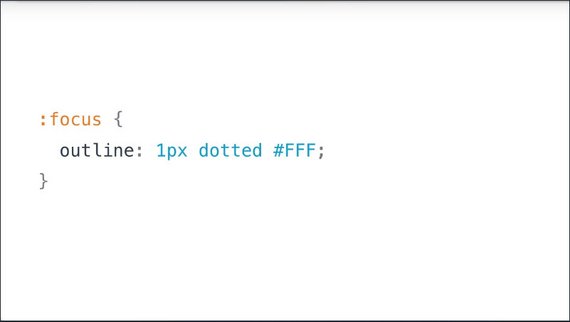

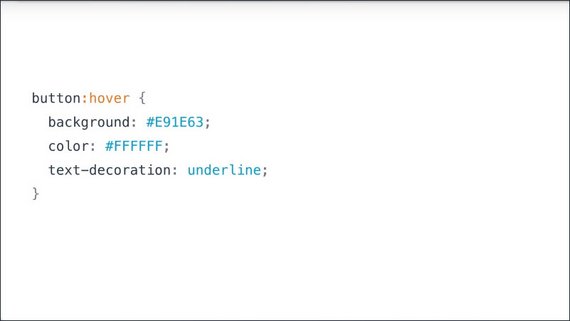

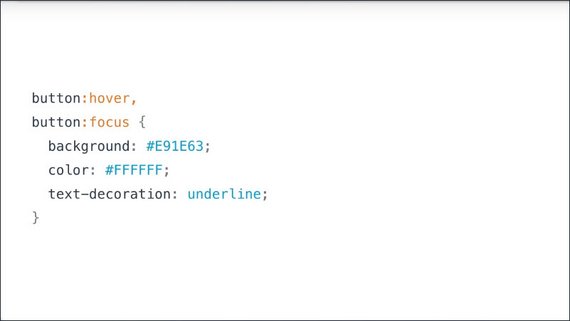

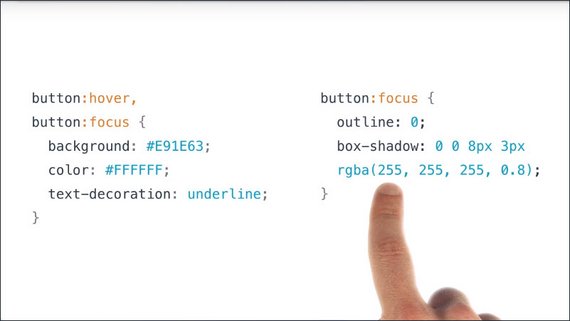

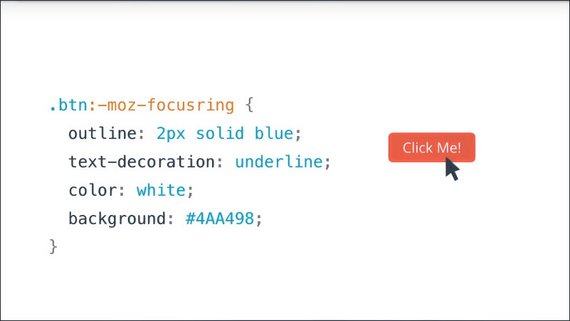

Then I can use the focus pseudo class to move the element back on screen. We’ll talk more about the focus pseudo class in a later lesson, but the short explanation is that this pseudo class matches anytime the corresponding element gains focus.

.skip-link {

position: absolute;

top: -40px;

left: 0;

background: #bf1722;

color: white;

padding: 8px;

z-index: 100;

}

.skip-link:focus {

top: 0;

}

With these simple techniques, we’ve removed the road blocks from the path of our keyboard users and greatly improve their experience.

You can read more about skip links in this article on the Web AIM site.

Google article on focus management: https://developers.google.com/web/updates/2016/03/focus-start-point?hl=en

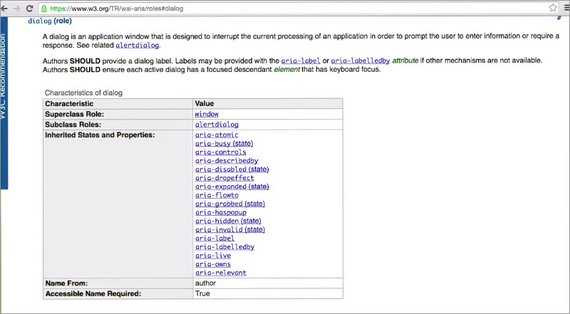

11.12 Focus in Complex Components

Managing focus when you navigate on the page is really important. But sometimes you’ll need to manage focus at the component level as well, especially if you’re building a complex custom widget.

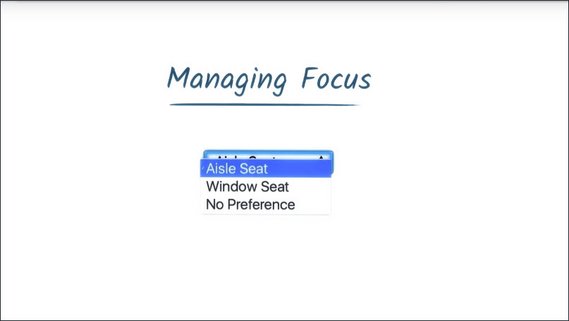

To show you what I mean, take a look at this native select tag and notice how I can focus it and once there, I can use the arrow keys to expose additional functionality, like selecting different options.

If you were building a custom select element yourself or something similar like a drop-down, you would need to expose these same kinds of behaviors so that your users who rely primarily on the keyboard could still interact with your control.

Now knowing which keyboard behaviors to implement can be a bit of a guessing game but, thankfully there’s a really helpful guide which you can refer to.

The ARIA design pattern stock, lists various kinds of components as well as the sorts of keyboard interactions that they support.

Now, Alice is going to cover ARIA in more detail in the following sections, but for now, let’s use this guide to help us add keyboard support to a new component which we’re going to build.

Resources

The ARIA Authoring Practices doc (or “ARIA Design Patterns doc”) is a great resource for figuring out what kind of keyboard support your complex components should implement.

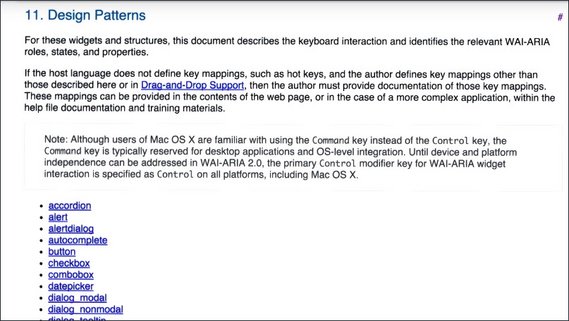

11.13 Keyboard Design Patterns

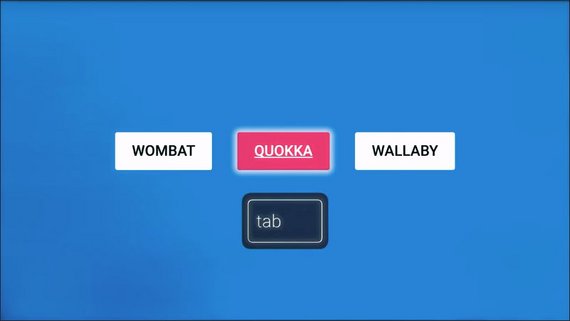

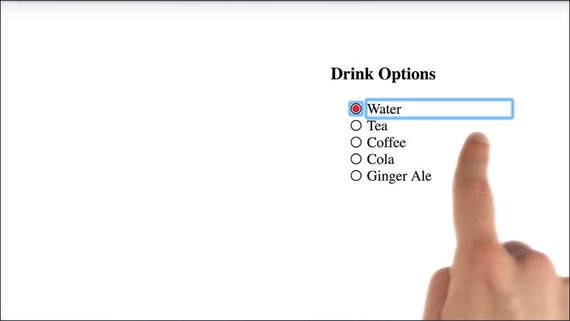

Here’s a custom component I’ve been working on which closely resembles a radio group.

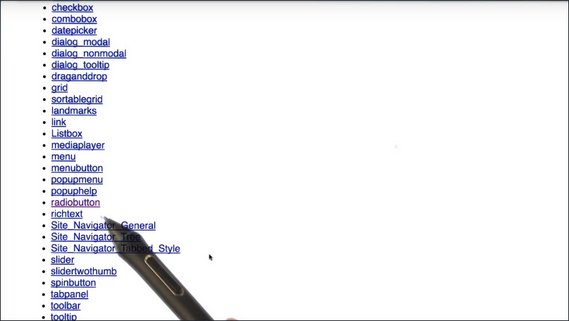

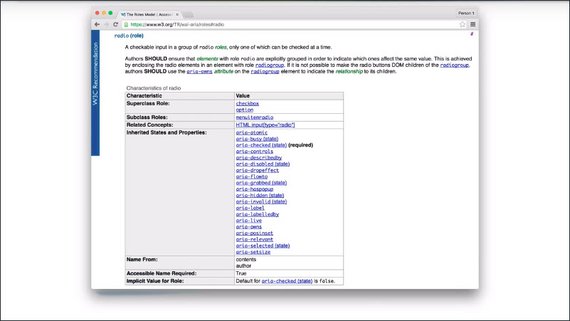

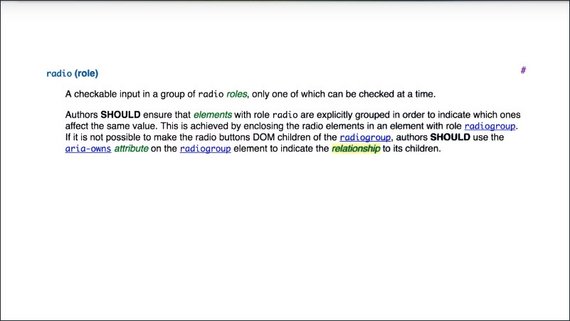

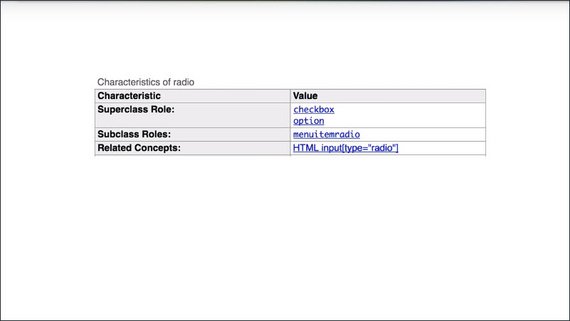

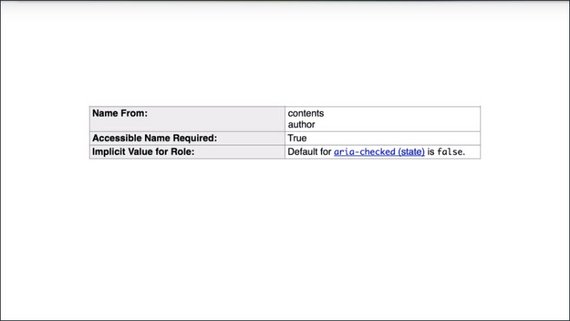

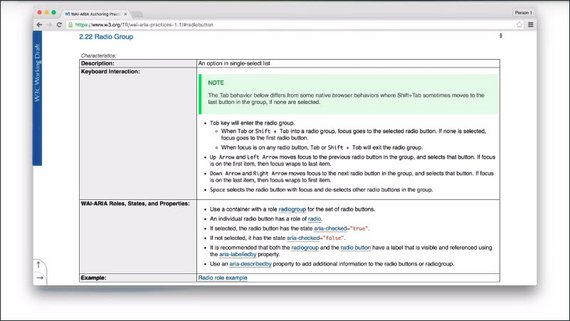

To determine what kind of keyboard support it needs, I’ll check the Aria Design Patterns guide and I then jump down to Section 11 which lists all of the various components and their patterns.

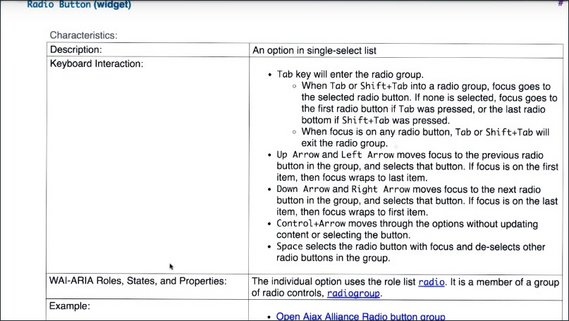

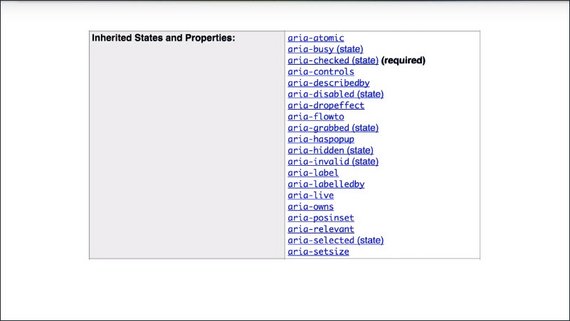

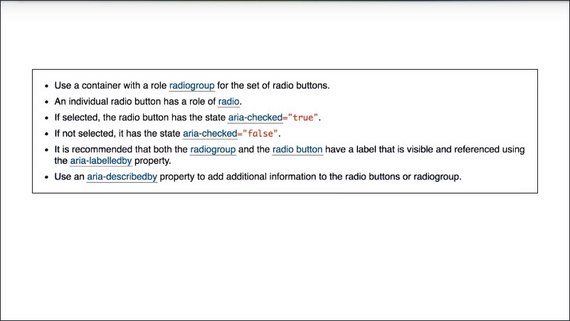

Once we’re down here, I’ll look for a component that sort of matches the one that I’m building. In this case I can see that there’s a radio button. So I’ll click on that and based on the recommendations there are a number of keyboard handlers that I know I now need to implement.

Using this guide I’m going to implement the Down Arrow slash Right Arrow support in my element. Now when the user presses the down arrow we know that our radio group should move focus to the next radio button, it should select that button, and if focus is on the last item, then focus will wrap around to the first item.

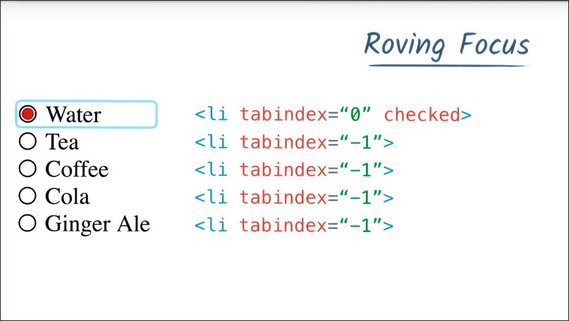

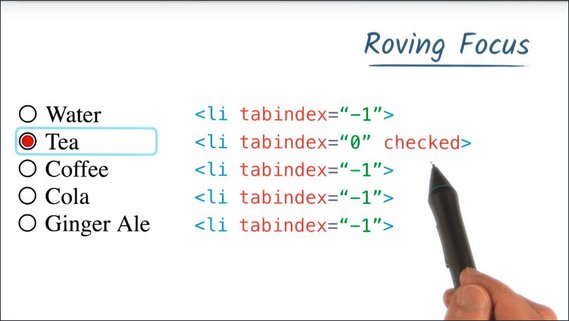

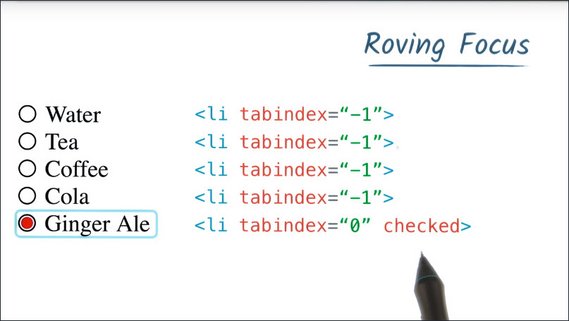

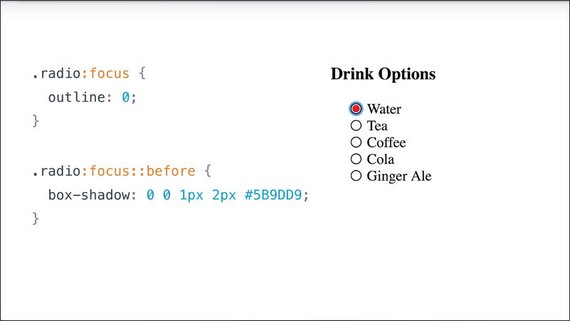

To do this, we’re going to use a technique called roving focus. Roving focus works by setting tab index to -1 for all of the children and then zero on the currently active item.

Our component then uses a keyboard event listener to determine which key the user has pressed. At which point we set tabindex on the next item to zero, we set tabindex of the previously focused item to negative one.

We call the focus method of this new soon to be focused item, this now moves our focus ring. And lastly I’m going to just move this checked attribute down to this element using setAttribute. In this case I’m using the CSS in my element based on that checked attribute to style the state of the radio button.

Now when I reach the bottom of this list and this last radio is focused and the user presses the down arrow, then we’re going to wrap back around.

So we’ll set tab index to zero on this top item. We’ll move checked over there or call focus and we’ll set tab index to negative one on the previously focused item.

For building complex components running focus is a really invaluable technique. So in the next lesson, you’re going to take a crack at implementing it yourself using the same example.

Resources

Take a look at the ARIA Authoring Best Practices guide to read more about the Radio pattern. I’ve linked to both versions so you can choose whichever one you prefer. Both patterns are nearly identical but do note that the 1.0 version is called “Radio Button” and the 1.1 version is called “Radio Group”.

https://www.w3.org/TR/wai-aria-practices/#aria_ex

11.14 Quiz: Adding Keyboard Event Listeners

You can find the files for this example in the lesson2-focus/05-radio-group directory within this course’s GitHub Repository.

Using the ARIA Authoring Best Practices doc (either version 1.0 or version 1.1) find the radio pattern and implement support for the Down Arrow and Right Arrow pattern using the “roving focus” technique. I should point out that you’ll also sometimes see this referred to as “roving tabindex.”

Note: The 1.0 version of the doc refers to this as a “Radio Button” whereas the 1.1 version of the doc refers to this as a “Radio Group”.

You’ll want to work in the radiogroup.js file to implement your keyboarding support.

Solution

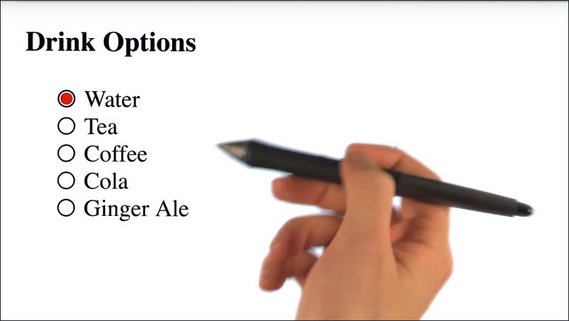

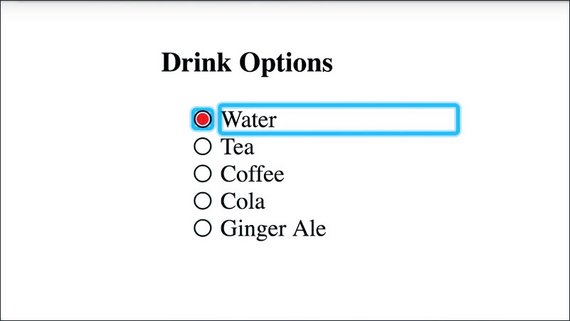

HTML

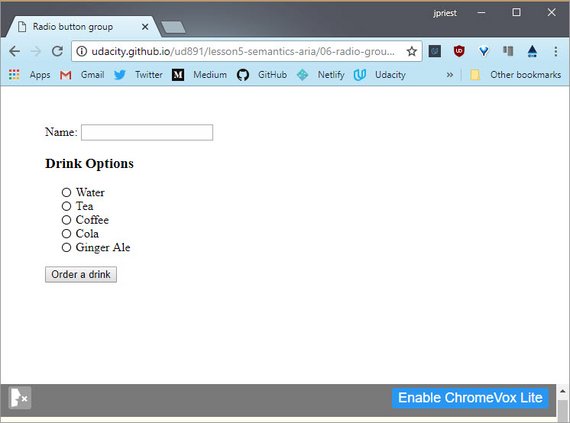

<body>

<div class="demo">

<h3>Drink Options</h3>

<ul id="group1" class="radiogroup">

<li tabindex="0" class="radio" checked>Water</li>

<li tabindex="-1" class="radio">Tea</li>

<li tabindex="-1" class="radio">Coffee</li>

<li tabindex="-1" class="radio">Cola</li>

<li tabindex="-1" class="radio">Ginger Ale</li>

</ul>

</div>

</body>

JS

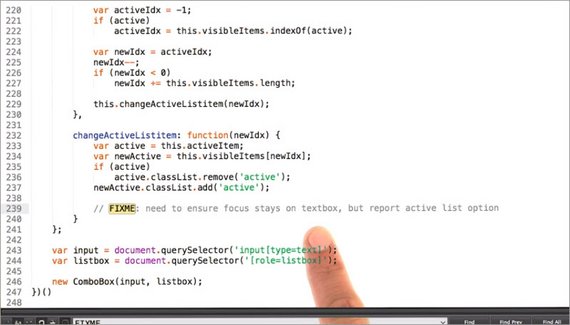

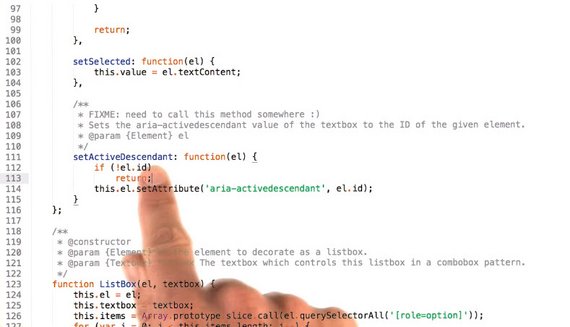

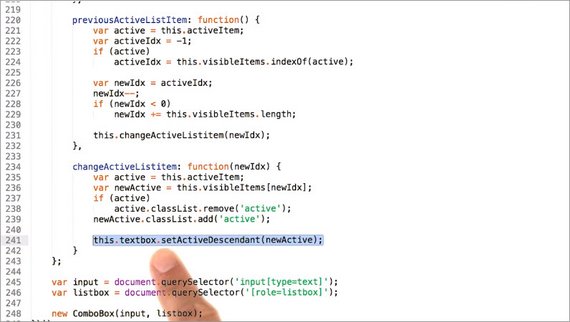

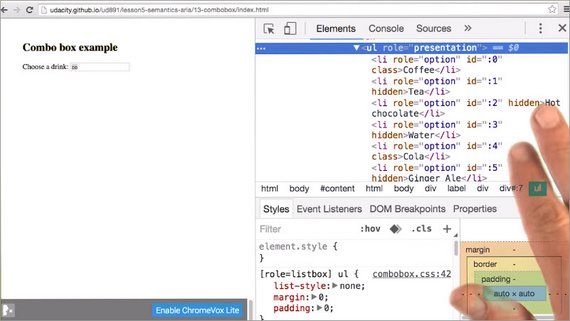

(function() {

'use strict';

// Define values for keycodes

var VK_ENTER = 13;

var VK_SPACE = 32;

var VK_LEFT = 37;

var VK_UP = 38;

var VK_RIGHT = 39;

var VK_DOWN = 40;

// Helper function to convert NodeLists to Arrays

function slice(nodes) {

return Array.prototype.slice.call(nodes);

}

function RadioGroup(id) {

this.el = document.querySelector(id);

this.buttons = slice(this.el.querySelectorAll('.radio'));

this.focusedIdx = 0;

this.focusedButton = this.buttons[this.focusedIdx];

this.el.addEventListener('keydown', this.handleKeyDown.bind(this));

}

RadioGroup.prototype.handleKeyDown = function(e) {

switch (e.keyCode) {

case VK_UP:

case VK_LEFT: {

e.preventDefault();

// This seems like a good place to do some stuff :)

if (this.focusedIdx === 0) {

this.focusedIdx = this.buttons.length - 1;

} else {

this.focusedIdx--;

}

break;

}

case VK_DOWN:

case VK_RIGHT: {

e.preventDefault();

// This seems like a good place to do some stuff :)

if (this.focusedIdx === this.buttons.length -1) {

this.focusedIdx = 0;

} else {

this.focusedIdx++;

}

break;

}

}

this.changeFocus(this.focusedIdx); // <-- Hmm, interesting...

};

RadioGroup.prototype.changeFocus = function(idx) {

// Set the old button to tabindex -1

this.focusedButton.tabIndex = -1;

this.focusedButton.removeAttribute('checked');

// Set the new button to tabindex 0 and focus it

this.focusedButton = this.buttons[idx];

this.focusedButton.tabIndex = 0;

this.focusedButton.focus();

this.focusedButton.setAttribute('checked', 'checked');

};

var group1 = new RadioGroup('#group1');

}());

11.15 Offscreen Content

Remember our previous lesson about making sure elements appear in the DOM in a way that makes sense for the tab order? Well, what do you do when you have content which isn’t on screen yet, but still needs to be in the DOM?

A good example of this is a responsive drawer panel. Now this is a really common UI pattern and it can present an interesting challenge for accessibility.

To illustrate this, here is the desktop version of that same site and I want you to notice what happens as I press the tab key. Focus will start off up here in the corner.

It will then move to the search input, then to the button in the upper right corner, and then it’s just going to disappear.

After pressing the tab key many more times, focus finally appears back on a link within the body of the page. So, what happened there? Why did it disappear?

That whole time that focus was off screen. It was actually hiding inside of this drawer panel going through and focusing all of these individual links.

Well this isn’t really a great situation to be in, and when you’re building an application you might occasionally find that as you’re tabbing around focus seems to suddenly just disappear.

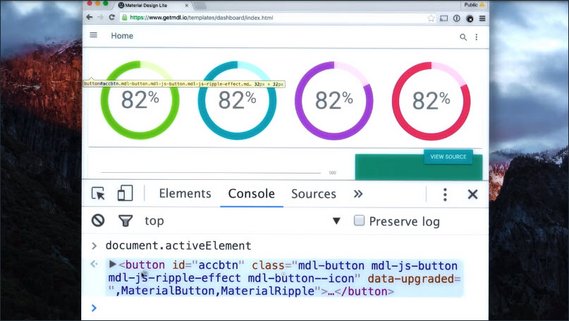

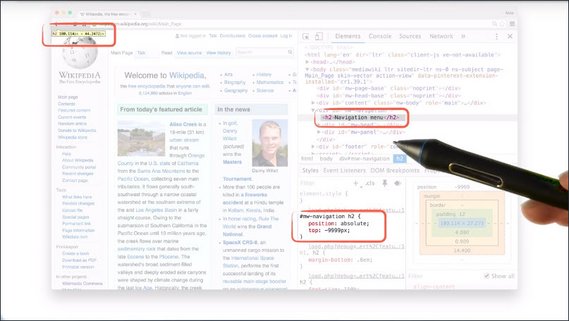

To figure out what’s going on, you may need to do a bit of detective work. If you’re tabbing around and you notice focus suddenly disappears, you can go into your console and log the document.activeElement.

Active element gives you a reference to the currently focused item,which in this case looks like some kind of fancy button. So you can go and look for our fancy button here in our source code and make sure that it’s not focusable.

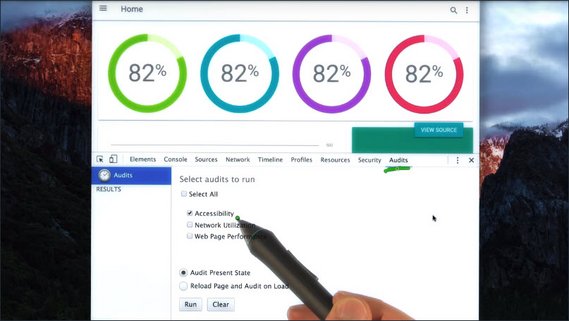

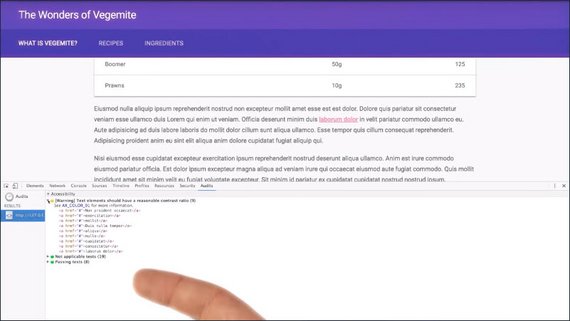

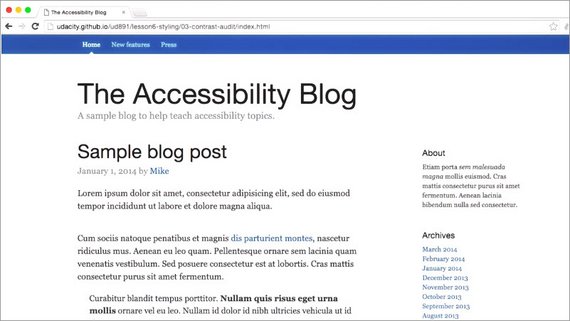

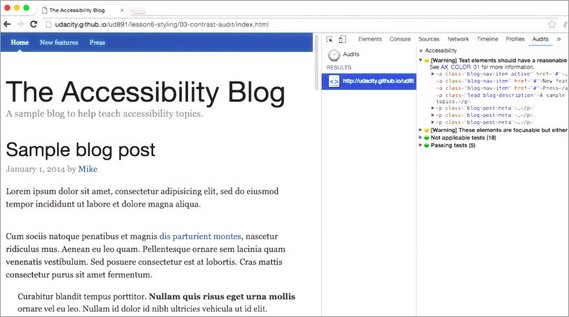

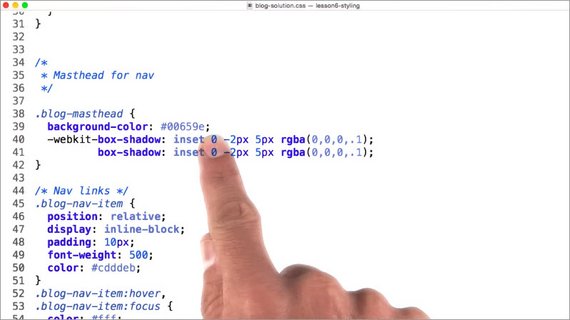

Another option to do our detective work is to use the chrome accessibility DevTools extension. The DevTools extension adds a number of useful features, including an inspector which will show you the accessibility properties of an element, as well as a set of accessibility audits.

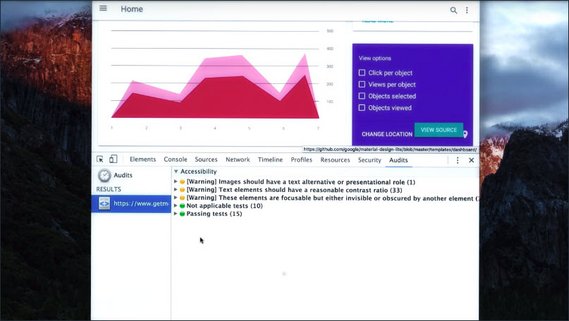

You can find these by opening the DevTools and going to the Audits section.

I’ve unchecked everything except for the Accessibility audit itself and I’m going to run it against the present state of my page. When I do this, you’ll see that it produces a number of errors, including items that are focusable, but either invisible or obscured by another element.

And looking at that list, we can see our fancy button and all of the other anchor tags inside of that off screen menu.

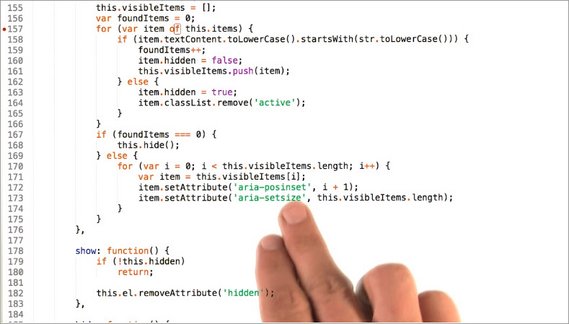

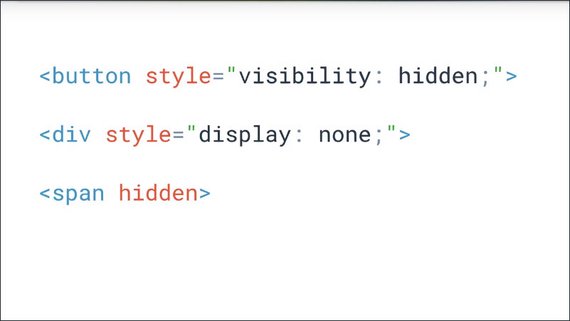

To fix the drawer menu, one option would be to set it to either display: none or visibility: hidden using CSS whenever it’s off screen.

This will prevent focus from being able to move into that element and focusing any of the child links inside of it. And then when the element comes back on screen, or just before it’s about to animate on screen, we can set it back to display:block or set the visibility back to visible.

Now in the next section, we’ll have you do some sleuthing of your own using these tools to find some off screen content and then to fix it.

Resources

To find your missing focus you can type the following into your console:

document.activeElement

Read more about Document.activeElement on MDN

Another tool you can use is the Chrome Accessibility Developer Tools Extension. This extension will not only add an Accessibility Properties panel to your Elements inspector, but it also adds an Accessibility option to the audits panel. Using this option you can quickly find accessibility issues in your page which you might have otherwise missed.

11.16 Quiz: Implementing Offscreen Content

The files for this exercise can be found in the lesson2-focus/04-offscreen-content directory within this course’s GitHub Repository.

Using either the Accessibility Developer Tools extension or document.activeElement see if you can track down the element that’s stealing focus and fix the page.

Solution

I used document.activeElement to find the offending (offscreen) button element. The button’s container was then set to display: none.

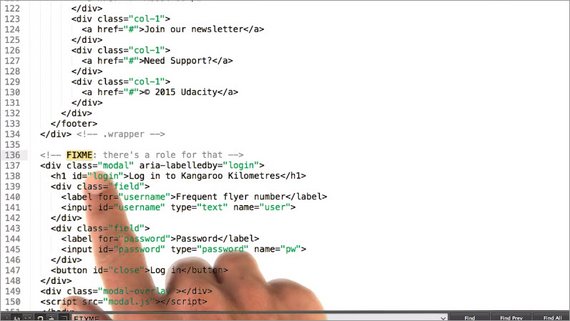

11.17. Keyboard Traps & Modals

We can sometimes run into trouble when building a widget if the widget functionality creates a keyboard trap. Let me show you an example.

Here I’ve got an autocomplete widget. I can press the Tab key to focus it. I can start typing, which will give me a list of city names. I can press the down key to focus one and then can press Tab again to complete the selection.

Now, the next thing I want to do is move to this next field by pressing Tab. So I’ll hit Tab once more and the focus does not change. What’s happening is this autocomplete thinks I’m still trying to finish my complete action. So no matter how many times I press Tab I’m just sort of stuck here.

This is what’s known as a keyboard trap. It can be very frustrating for users. In fact, Section 2.1.2 of the WebAIM checklist specifically calls this out. Stating, the keyboard focus should never be locked or trapped at any one particular page element.

The user should be able to navigate to and from all page elements using just their keyboard. But strange as it may seem, there are times when this behavior is actually desirable.

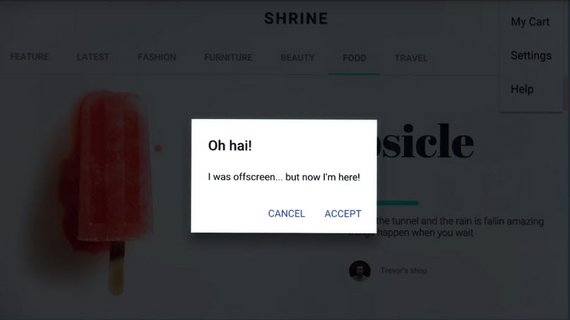

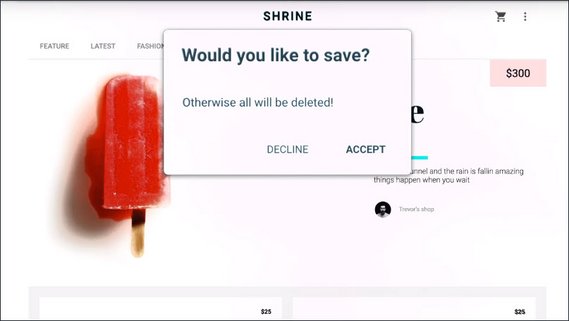

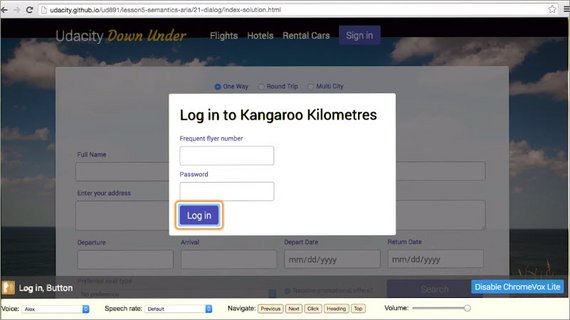

Take for instance, the modal window.

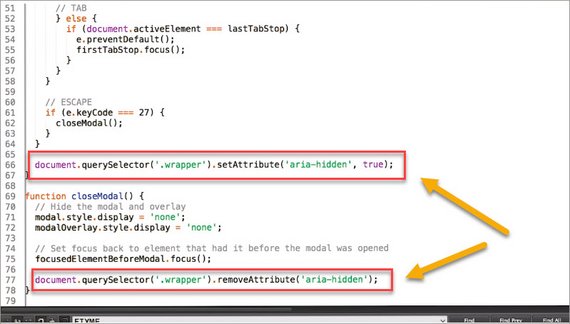

Now, normally when a modal window is displaying on screen, we don’t want the user to be able to access any of the content behind it. Oftentimes developers will add an overlay to cover the page, but that doesn’t stop keyboard focus from accidentally traveling outside of the model.

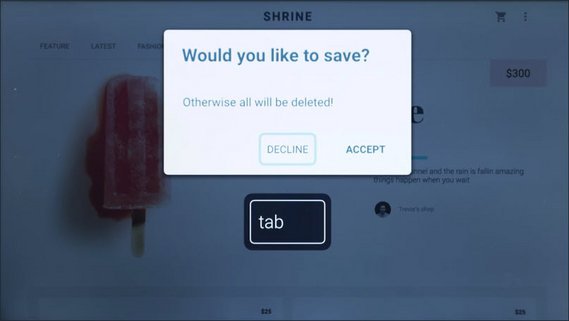

Here, I’ll tab through this dialog. So I’ll press the Tab key, which will focus the Decline button.

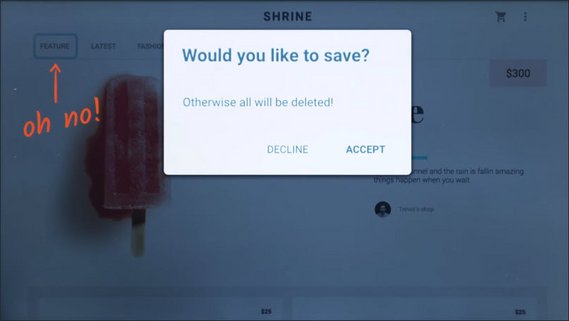

I’ll tab again, which focuses the Accept button. And I tab one more time. No, it looks like our focus has now moved behind the modal window.

Now in instances like this what we want is a temporary keyboard trap to ensure that we track focus within the modal wall it’s displaying. And then that we can restore it to the previously focused item once the model is closed.

This can be a tricky technique to implement, and while there are proposed ideas on how to make it easier for developers, for instance, like this dialogue element here, they don’t currently have widespread browser support. Meaning, we’re going to have to roll up our sleeves and implement this ourselves.

So here’s an example of what I’m going to try to build. I’ve got a little open modal button in the top corner and when I focus it and hit Enter, I get a modal dialog.

I can tab through it, and the focus is trapped. I can hit the button and it closes the model dialog. I can hit Escape or click the background, and it’ll close it and restore focus to that button.

- The app can be view here: Modal Keyboard Trap

- The code can be viewed here: GitHub source for Modal Keyboard Trap

Now I realize this is a ton of code. I sort of think of the accessible model window as one of the boss battles in accessibility. So, what I want you to do in the next lesson is use some of this code to implement a modal window yourself. And that way you’ll have a deeper understanding of how all of this works.

Resources

WebAIM checklist items:

11.18. Lesson Summary

Using the skills we’ve covered in this lesson you should now be well equipped to implement a solid focused strategy in your application.

The next step is to take all these various interactive controls that we’ve been working with and start to infuse them with some meaning.

For instance, when a screen reader lands on your custom radio buttons, how is it going to tell the user that these are in fact radio buttons and not just a bunch of divs. For that, we’re going to need to learn about semantics and I’m going to turn it over to Alice to tell you all about it.

Lesson 12. Semantics

12.1 Semantics Introduction

We just saw how we can make things accessible to anyone who can’t use a mouse or pointing device. Whether that’s because it’s any type of physical impairment or a technology issue or simply personal preference.

You would have seen that, while it definitely requires some care and thought, it’s not a huge amount more work if you plan it from the beginning. Once that work is done, you’re already a long way down the path to a fully accessible site.

Already, you’ve made your site usable by more people than if you hadn’t addressed keyboard usability, and given your site a more polished completed feel.

In this lesson, we’re going to build on that work and get you thinking about other accessibility factors like how do we build our websites to support users like Victor who can’t see the screen at all.

We’ll start with some background on assistive technology, the general term for things like screen readers. These are tools that are designed to help users whose impairments can prevent them from accessing information technology at all.

Next up, we’ll take a look at the general user experience concepts. We’ll build on this to take a deeper dive into the experience of users of assistive technology.

Then finally we’ll move in to how we can use HTML effectively to create a good experience for these users and we’ll see that actually does overlap quite a lot with the way we address focus.

First, let’s talk a bit about assistive technology.

12.2 Assistive Technology

Assistive technology is an umbrella term for a broad range of devices, software, and tools that help any person with a disability complete a task.

In the broader sense this include something as low tech as a crutch to help someone walk or magnifying glass to assist reading, or as high tech as a robotic prosthesis or image recognition software running on a smartphone.

It can include something as general as browser zoom or as specific as a custom-designed game controller. It can be a separate physical device like a braille display, or be implemented completely in software like voice control. It can be built into an operating system like some screen readers or it can be an add-on like a Chrome extension.

Assistive technology in particular is pretty blurry. After all, all technologies being built to assist people with some task or another, and things often move in and out of the assistive technology category.

For example, one of the earliest commercial speech synthesis products was a talking calculator for the blind, and now we see speech synthesis popping up all over the place, from driving directions to virtual assistance.

On the other hand, technology which is general purpose often finds an assistive use. For example, people may use their smartphone’s camera zoom to get a better look at something small in the real world.

In the context of web development we’re still talking about a diverse range of technologies that we want to support. People may interact with your website using a screen reader or braille display with a screen magnifier, via voice control, using a switch device, or some other form of assistive technology which adapts the page to create a more specific interface that they can use.

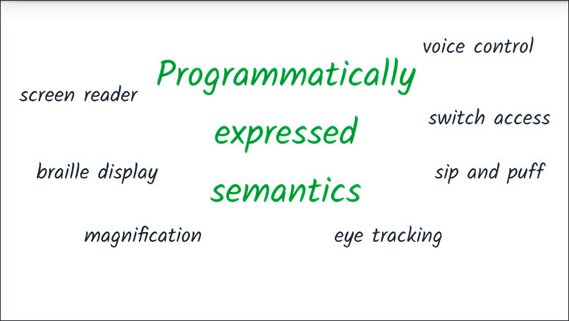

For all of these technologies, ensuring that our website support assistive technology uses is going to come down to programmatically expressed semantics. But before we can explain exactly what programmatically expressed semantics refers to, we need to talk a little bit about affordances.

12.3 Affordances

When we use any manmade tool or device, we typically look to its form and design to give us an idea of what it does and how it works.

A classic example is a kettle.

I can look at this kettle and recognize that the handle side is the one I’m meant to grab, even if I’ve never seen one before, because I’ve seen the same basic shape on things like coffee mugs, pots, pitchers, and various other things.

It serves a practical purpose. It’s shaped so I can comfortably get my hand around it, and it’s insulated. But also, the fact that I’ve seen many similar handles before gives me a visual clue here. After all, I could probably pick the kettle up by the spout if I really wanted, although I’d probably end up burning myself, and it’d be pretty tricky to pour water out of it.

When it comes to graphical user interfaces, affordances still represent the actions we can take, but now they’re more metaphorical since there’s no physical object to interact with.

Some classic examples of technology affordances are buttons, you will be hard pressed to find any software UI without at least one button on it, and sliders from scroll bars to playback controls to price limits.

Something I like to think about is how real world objects get translated into purely visual metaphors to create those affordance cues for graphical user interfaces. For example, you can clearly see a button on a keyboard reflected in a button element and a checkbox on a ballot paper in a checkbox element.

While some graphical UI influences may not be immediately obvious to new users, for example,someone new to computers might need to experiment to learn to use scroll bars. People generally learn the visual cues quickly with little or no training.

Well designed affordances enable people to do something with as little training as possible.

12.4 Quiz: Affordances

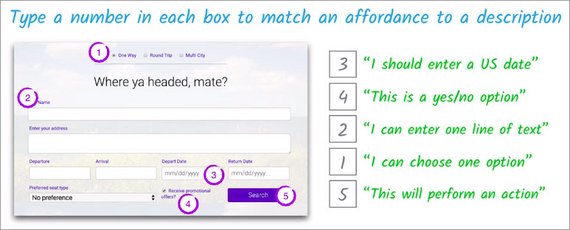

The next quiz is all about thinking about what we know about the graphical UI affordances provided by HTML. Let’s take a look at some of the most common affordances we see on webpages.

All of the form elements we use on that flight-booking site have some familiar semantics which give us cues as to how we use them.

In this exercise all you need to do is match up a screenshot of the UI element with the semantic meaning on the right.

Solution

This date field means I should enter the US date.A check box is a yes or no option.Here, I see I can enter one line of text.Radio buttons mean I can choose one option.And this button here let’s me know it will perform an action.

12.5 Semantics & Assistive Technology

So that’s a little background out of the way. Now you can probably see where I’m heading with all this. Someone who can’t see the screen, can’t access the visual information in the interface. And someone who is using voice control relies on the voice control software being able to interact with the web page.

So we need to make sure that information is expressed in a way which is flexible enough to be accessed programmatically by assistive technology, which can then create an alternative user interface to suit its users needs.

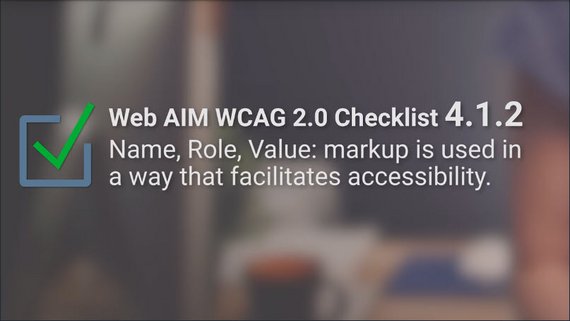

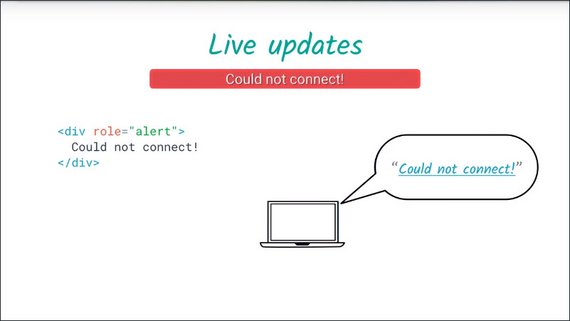

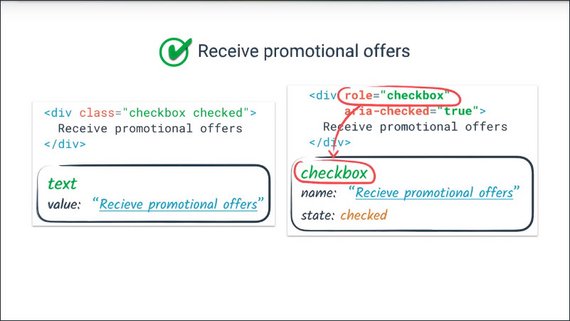

We refer to this as expressing the semantics of an element. The Web AIM checklist explicitly calls this outing guideline 4.1.2, saying “Name, Role, Value: markup is used in a way that facilitates accessibility.”

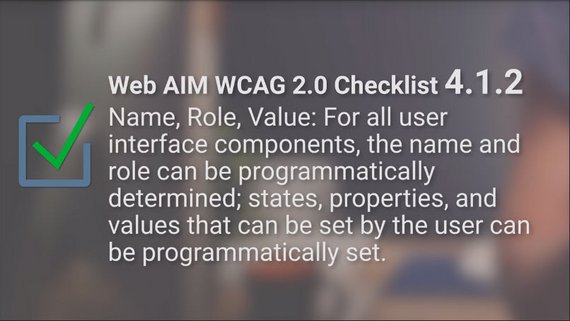

Okay, that’s kind of terse. The Web Content Accessibility Guidelines go into a bit more detail. “For all user interface components, the name and role can be programmatically determined; states, properties, and values that can be set by the user can be programmatically set.”

So what are name role and value, and how can we make sure that they can be programmatically determined and set? To answer that, we’re going to start off by trying things out from the point of view of someone using assistive technology.

Just before we jump into that I want to quickly mention that in this course we will be working mostly with screen readers, but a lot of the work we do to support screen readers also benefits users who use other assistive technologies. Things like voice control and switch control use the same programmatically expressed semantics.

In the introduction we had a first look at using a screen reader. Now were going to try using one without any access to the web pages visible interface.

12.6 Quiz: Screen reader 1

Now let’s book a flight using a screen reader. We’ve modified the flight reservation page, so that you can’t see what you’re doing anymore. You’ll have to use the screen reader.

You might want to refer back to the earlier exercise if you get stuck. Use the provided form to book a one way ticket to Melbourne with a window seat.

Try out the [flight booking form](http://udacity.github.io/ud891/lesson3-semantics-built-in/02-chromevox-lite/, then come back here once you’ve successfully filled it out.

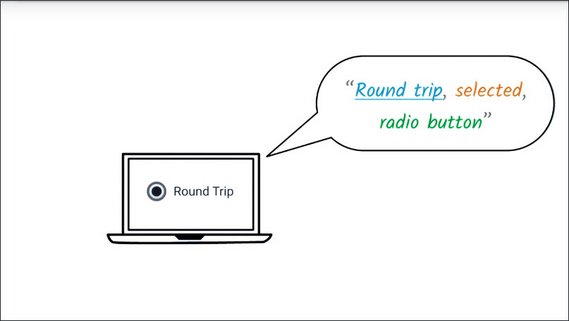

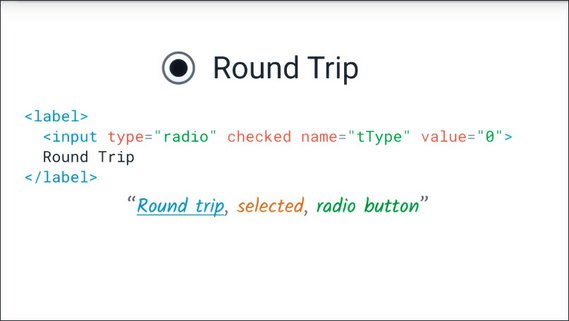

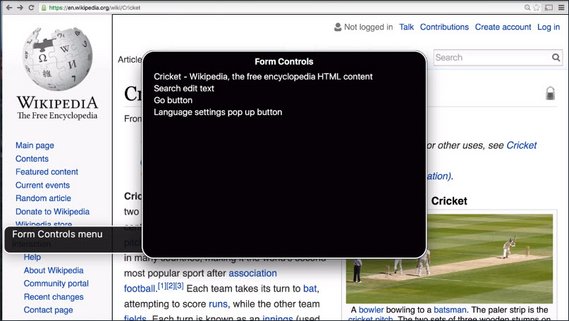

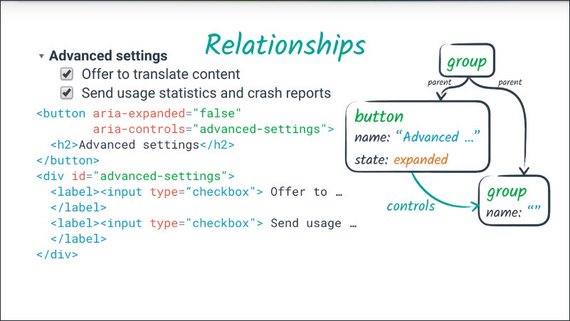

12.7 Role, Name, Value

A screen reader actually largely creates the user interface for the user based on the programmatically expressed semantics.

Instead of a visual UI, the screen reader provides an auditory interface.

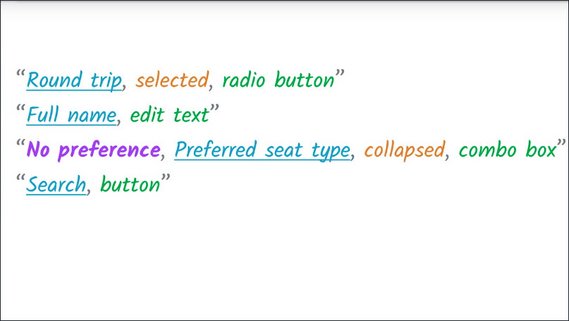

You probably noticed in the previous exercise that the screen reader told you some information about each element.

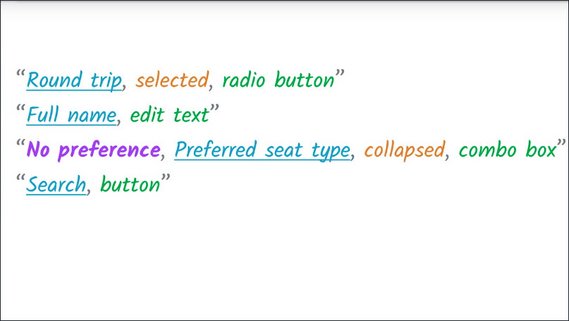

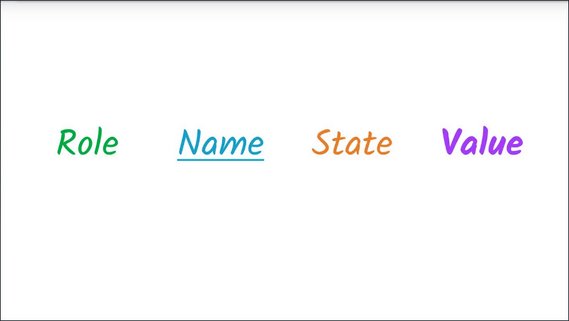

Roughly speaking, we can expect some subset of the following information to be expressed.

- What type of element it is? We call this an elements role (green). Sometimes a screen reader might simply state the element’s role, other times it might play an easily recognizable sound to avoid constant repetition. Sometimes it might do both.

- The screen reader will announce an elements name (blue), if it has one.

- It will announce what its value (purple) is, if it has one.

- It will also announce any information it has about an element’s state (gold).

So broadly speaking, if we’ve done things right, we can expect to hear information about an element’s role, name(label), state, and value.

12.8 Quiz: Screen reader 2

This time we have a different form which we’ve hidden from view again. Let’s use the screen reader to find the first form field, and then we want to find out its role and its label.

Visit the mystery form and use ChromeVox Lite or another screen reader to find the first form field. What role and name does it have?

Solution

Identify the role and label of the first form field:

If I press the Tab key, it takes me straight to the first form field. It announces:

“Your email address, edit text.”

So its Role is, “edit text”, and its Label is, “your email address”.

- Role: Edit text

- Label: Your email address

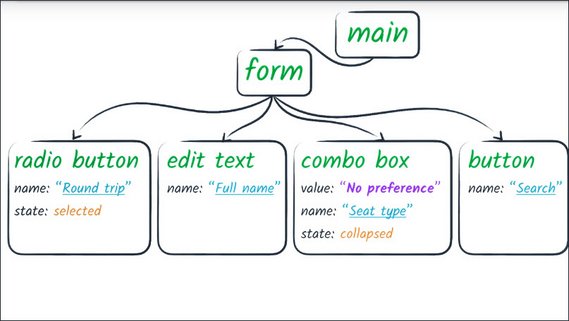

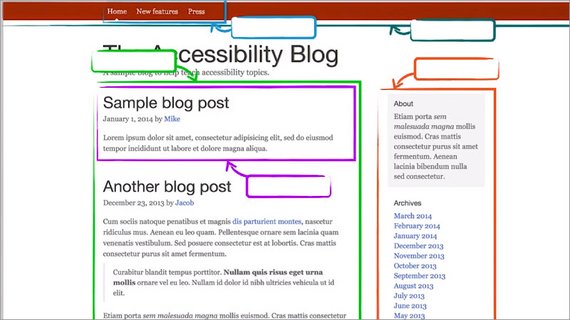

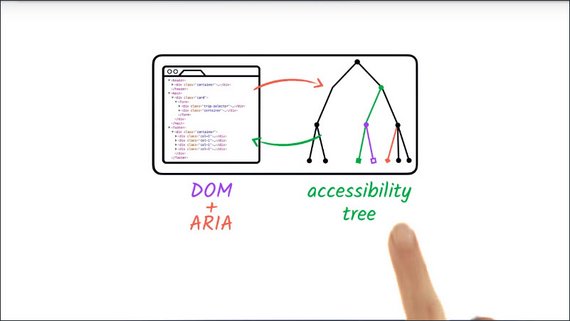

12.9 The Accessibility Tree

Okay, this might sound a bit strange but imagine you’re building a user interface for screen reading users only.

So you don’t need to create any visual UI at all. Just provide enough information for the screen reader to use. How would you express the form interface we used in the previous exercise?

Well, what you’d be creating is kind of an API describing the page structure. That sounds kind of like the DOM API, but we can get away with less information and fewer nodes because a lot of that information is useful only for visual presentation.

Something like this.

This enables a screen reader user to jump in between high level sections and then get enough information about each form element’s affordances to know how to fill them in.

Remember, for a screen reader user, the screen reader provides the affordances based on the role alone without caring about the visual style.

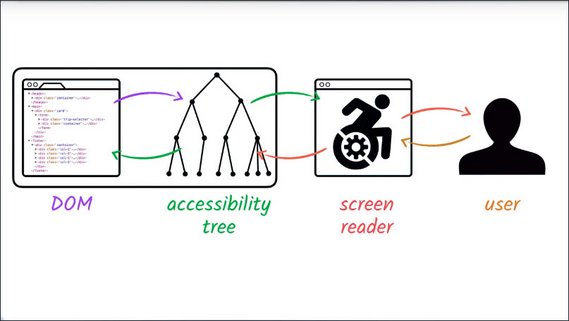

This is more or less what the browser actually does present to the screen reader. What happens is that the browser takes the DOM tree and modifies it to turn it into a form which is useful to assistive technology.

We refer to this modified tree as the accessibility tree.

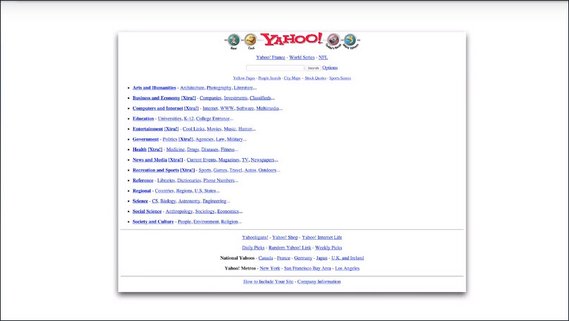

In my mind, the accessibility tree conceptually looks a bit like an HTML page from the 90s. You may have seen web pages that look like this. You can picture the mark up, I’m sure. A few carefully chosen images, a lot of links, a text box and a button.

Visually scanning down the page in this case gives you an experience pretty similar to what a screen reader user would get.

12.10 Quiz: DOM & A11y tree matching

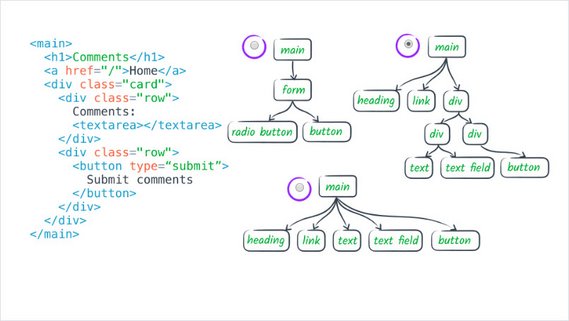

Which of these accessibility structures matches the DOM structure on the left?

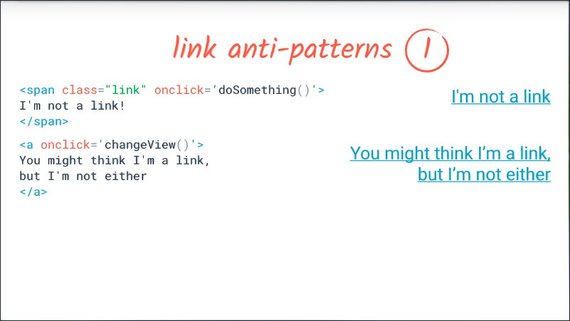

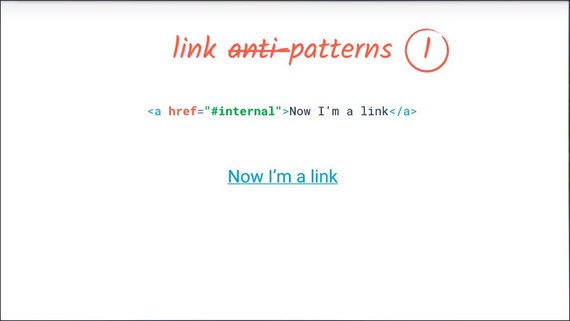

12.11 Semantics in Native HTML

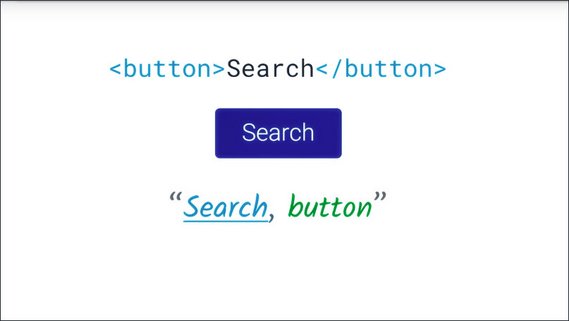

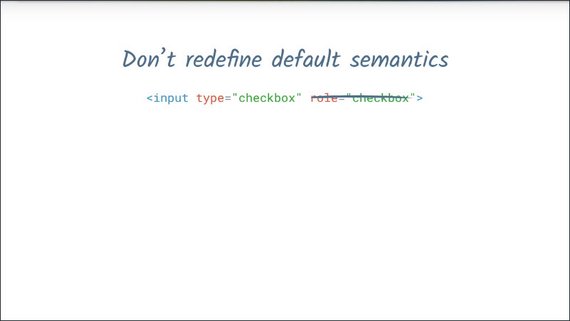

So you have the DOM tree and we know the browser transforms this into the accessibility tree.

It can do this because much of the DOM has implicit semantic meaning. That is, the DOM is using standard native HTML elements that are automatically recognized by browsers and work predictably on a variety of platforms.

Accessibility for native HTML elements such as the standard link or button, is handled automatically as well.

We can take advantage of that built in accessibility by writing HTML which expresses the semantics of our page directly.

12.12 Quiz: Writing Semantic HTML

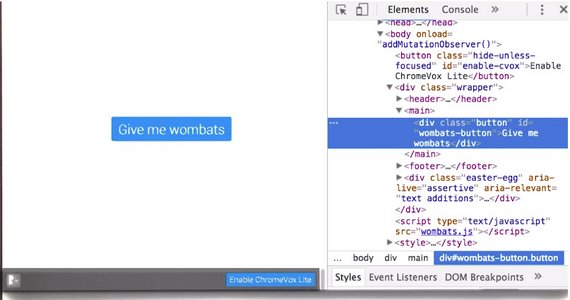

In this example, we have a single element on the page that looks like a button, but if we take a look at the HTML source, we can see it’s not actually a button. If we try to use it with the screen reader, we’d run into problems.

Rewrite this code so it’s more semantic in nature, and if you get it correct, you’ll find a secret word up at the top.

This exercise can be found in the folder lesson3-semantics-built-in/05-writing-semantic-html within this course’s GitHub Repository, or you can access the live version.

Solution

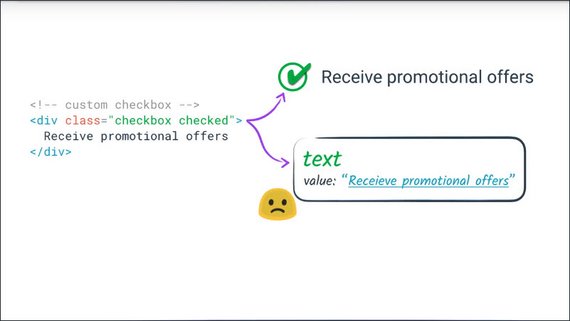

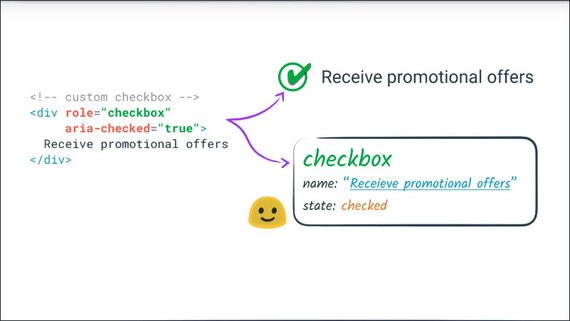

When we don’t use a button element the screen reader has no way of knowing what it’s landed on. Plus we’d have to do all the extra work we talked about in the previous lesson to make it usable to keyboard only users.

Right now I can only use this button with a mouse.

We can easily fix this by using a regular button element, instead of a div. This also has the added benefit of taking care of keyboard interactions for us.

Once we’ve fixed the button we now have our secret word.

12.13 Writing Semantic HTML: Name Game

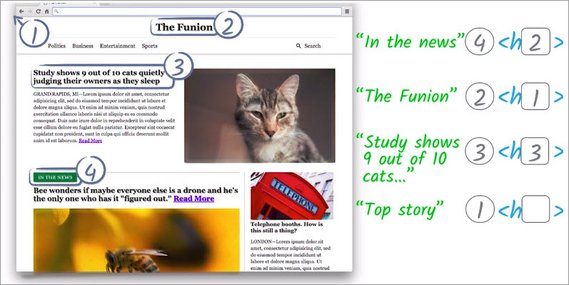

Earlier we saw that screen readers will announce an element’s role, name, state and value, not necessarily in that order.

By using the right semantic element, we’ve got role, state and value covered, but we also need to make sure that we’re making element’s name discoverable.

This is actually the very first item on web aims checklist: “Provide text alternatives for any non-text content.”

At this point, I’m going to take a quick tangent on technology. We’re in the unfortunate position of having all of these terms, each of which is overloaded in its own particular way in HTML, which are also used in various contexts to refer to the same central concept we’re talking about in this lesson.

Since the way the term label is used in HTML is closest to what we mean here, for the rest of this course, I’m going to refer to label interchangeably to refer to this concept. But please keep in mind that in the context of role, name, value, and state, the name means the same thing.

With that out of the way, let’s talk a bit about labels. Broadly, there are two types of labels: visible labels, which are used by all users to associate meaning with an element, and text alternatives which are only used when there’s no need for visual labels.

So, here we’ve got an image that is self-explanatory to anyone who can see the image, and by its very nature, a text alternative is usually not visible on the page.

So in this case, we can see this image of bees swarming. An assistive technology user would simply have access to this bee swarming label.

The checklist provides a list of recommendations for how to create visible and non-visible labels.

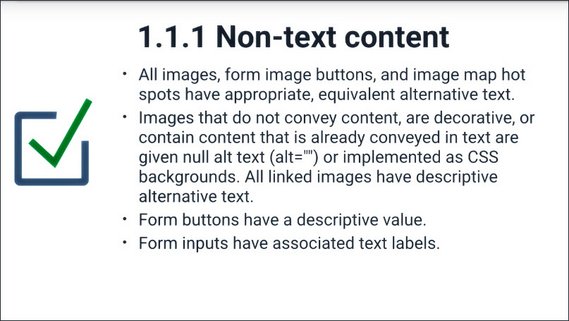

The easiest is the third item: “Form buttons have a descriptive value.”

A button typically has some text content, and that acts as the button’s text alternative. Since this text is visible to both sided users and technology, we’re lucky, because we don’t need to do any more work to create a good experience for our assistive technology users.

So that’s an easy one to check off.

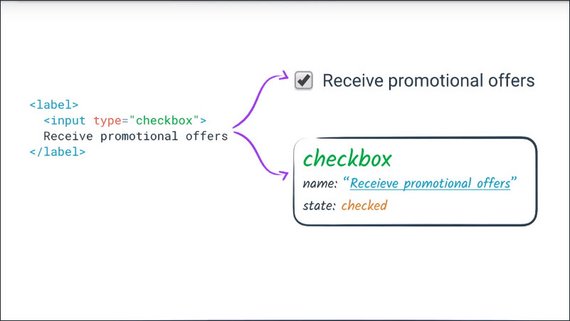

Next we need to check that, “Form inputs have associated text labels” (item four).

When we create a form input like a check box and just put some text next to it, we get a visual label, but we didn’t actually create a programmatically accessible label for the element we’re trying to label.

Also, we don’t get the nice behavior where we can click on the label to toggle the check box.

We can fix this by using a label element. We can either wrap the input element like this…

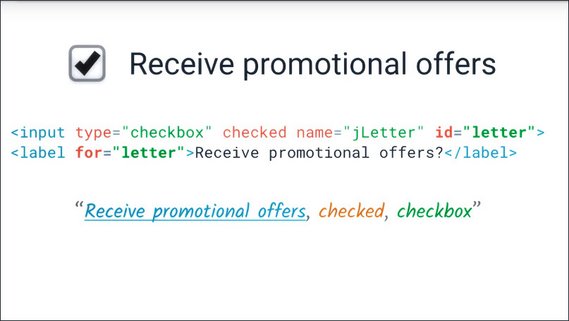

or we can use the for attribute on the label. If we do that we need to make sure to give the input element an ID and use the same ID as the value of the for attribute.

That creates an association between the label element and the input element, whichever of these two methods we use, we will get an accessible label for the check box, and we’ll be able to toggle the checkbox by clicking the label.

Resources

WebAIM Guideline 1.1: http://webaim.org/standards/wcag/checklist#g1.1

The MDN page on <label> demonstrates the two options for associating a <label> with the thing it’s labelling.

The W3C spec has a list of what types of elements work with a <label> tag.

12.14 Quiz: Labeling Input Elements

This form is mostly marked up well but we have one form element which doesn’t have a label correctly associated with it.

By going through with the screen reader find the element and fix that issue.

This exercise is flight-booking.html and can be found in the folder lesson3-semantics-built-in/16-labelling-input-elements/ within this course’s GitHub Repository, or you can access the live version.

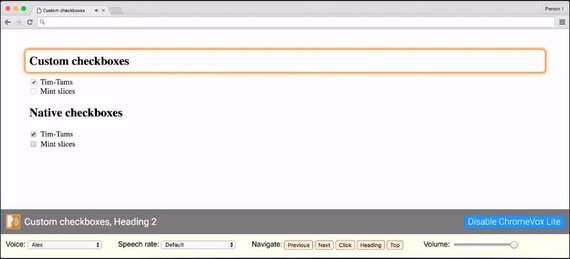

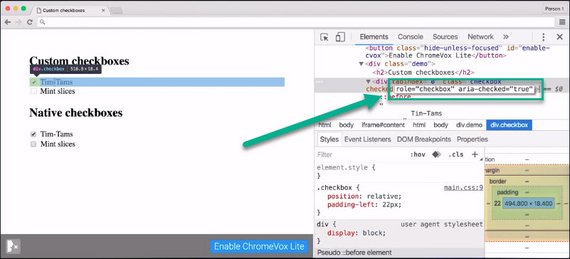

Solution

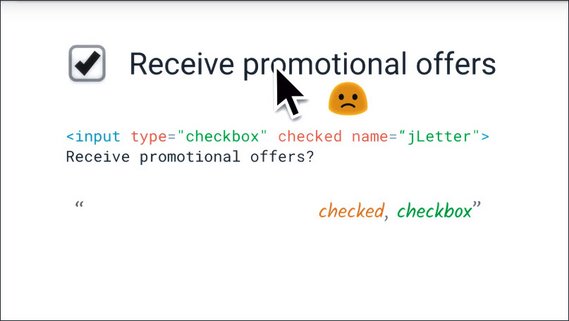

First, we’ll identify unlabled contents by using the screen reader.

TAB “Checkbox checked.”

The “promotional offers” checkbox isn’t labeled.

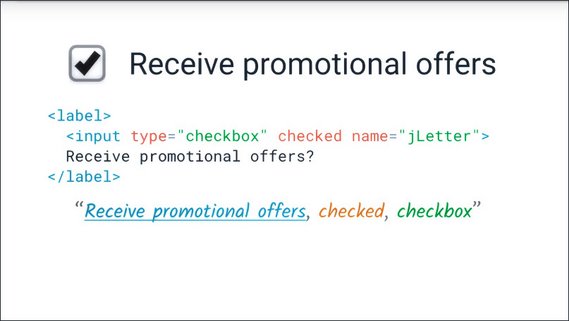

There are two ways to associate a label with the form element. Either of these methods will cause the label text to become a click target for the checkbox, which is also super helpful for pointer based users.

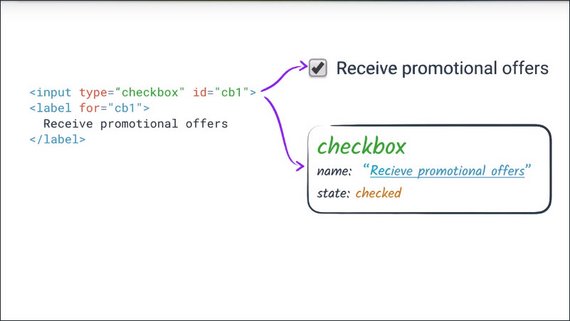

We could wrap the input element in a label element, or we could use the for attribute of the label to associate it with the ID of the input.

TAB “Receive promotional offers, checkbox checked.”

Once the checkbox has been labeled correctly we can see that it has a role of “checkbox”, its state is “checked” and it has a label of “receive promotional offers”.

12.15 Text Alternatives

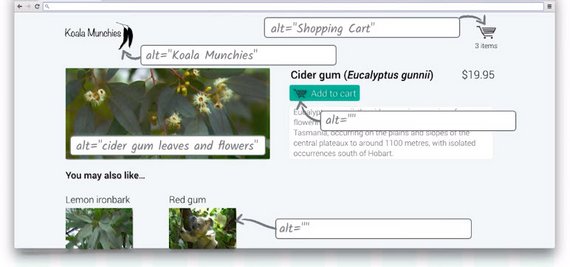

Let’s have a look at text alternative for images. We can use the alt attribute to provide a text alternative for images, however, we need to think about what role an image plays in the page to work out what type of text alternative it should have.

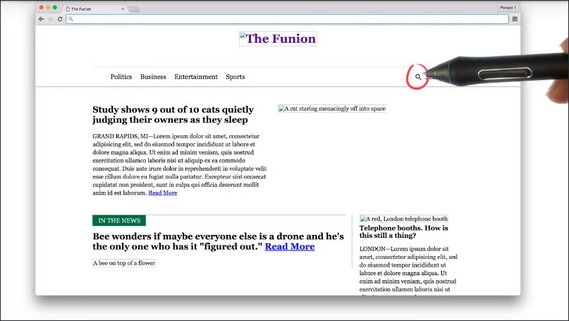

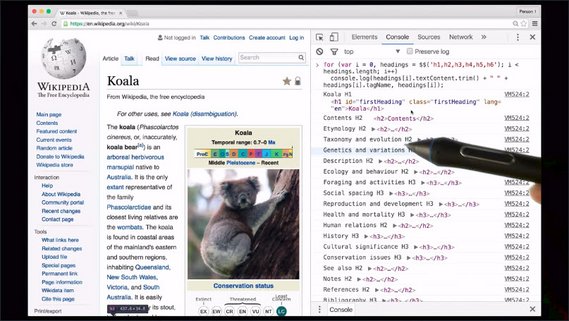

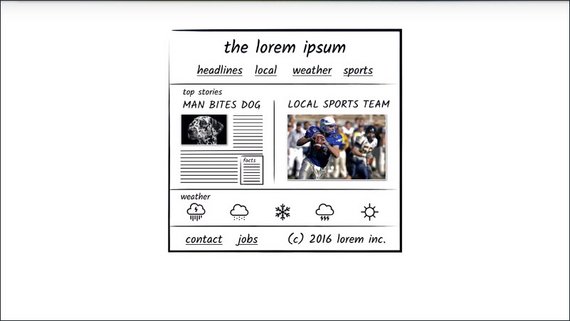

Let’s have another look at this newspaper page from the previous lesson. I’ve got VoiceOver running and I’m going to use the mouse pointer Moves VoiceOver Cursor option to let me quickly inspect things for VoiceOver.

Now, you probably don’t want this on all of the time but it can be good for quickly testing things.

All right.So here, we have a picture of a cat illustrating that article on cats.

VoiceOver announces this as.

“HTML content. slash one six zero two zero…(/160204193356-01-cat-500.jpg)”

Okay, so that was pretty sub optimal.

I can pull up DevTools on the image and add an alt attribute which says, “a cat staring menacingly off into space.”

All right, so now I can try VoiceOver again

“HTML content, a cat staring menacingly off into space.”

And now you have a nice succinct description of the image.

A couple comments on the alt attribute. Alt allows you to specify a simple string to be used whenever an image is not available, whether the image fails to load or you’re a web crawling bot or a screen.

Alt differs from any other type of caption, including a title, in that it will only be used if the image isn’t available. Caption or title typically provides extra context for the image, rather than an alternative to the image.

Writing useful alt text is a bit of an art. In order for a string to be a usable text alternative it needs to convey the same thing as the image in the given context.

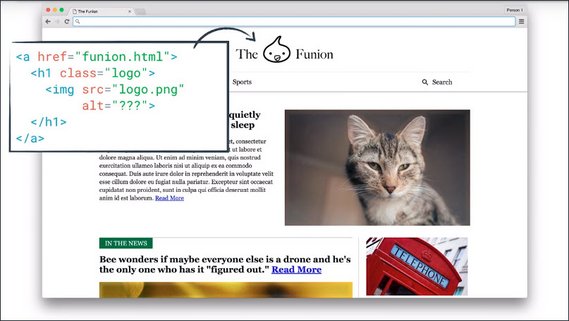

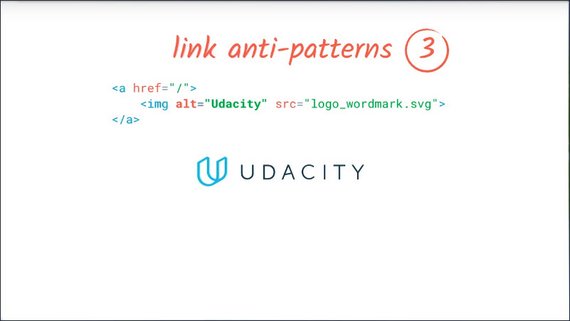

To give a more complex example, we have that logo image in the masthead link. That link is going to take us back to the homepage so it might be tempting to write home here.

That’s not a functional alternative to the image. It’s actually going to create a more confusing experience, because then we might get the idea that it’s an image of some kind of home.

Instead, we can describe this image pretty accurately simply as “The Funion”.

You may or may not want to explicitly call out that it’s a logo, but given it’s an image, that’s more or less implied anyway.

An easy way to check whether alt text is sensible, is to imagine all your images are broken.

Can you still understand the page content?

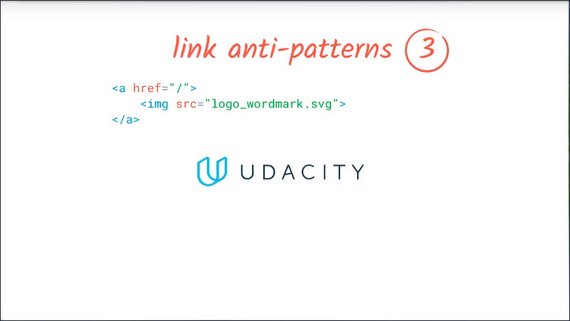

Now there’s one image I left in here that I’d like to take a closer look at. You have this magnifying glass logo, inside the search link.

If I checked it out with the VoiceOver,

“Magnifying glass”

I can hear that we’ve hopefully added an alt text of magnifying glass, but if I inspect the link as a whole.

“Magnifying glass search link.”

We can hear that it is actually redundant.

“Magnifying glass search” doesn’t convey anything that search doesn’t. But we know that if we leave the alt text out, we’ll probably hear the image filename which we already saw as a potentially horrible experience.

So in this case, I’m going to to use an empty alt text (alt=""), and we’ll see what that does.

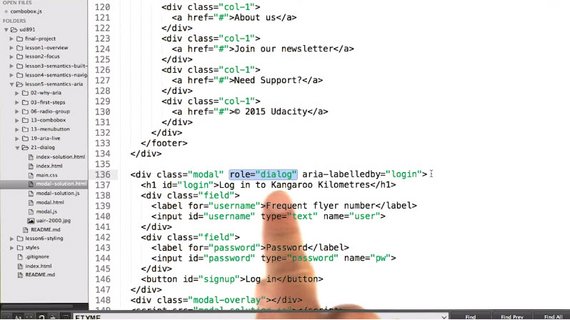

The empty alt text actually removed the image from the accessibility tree altogether, so the image is now completely skipped by the screen reader. In this case it’s actually what we want, because the image was redundant.