<– back to Mobile Web Specialist Phase 1 Notes TOC

Lesson 2.5: Classes

Notes from Lesson 2: Functions of ES6 JavaScript Improved by Richard Kalehoff and James Parkes. This class is part of the Udacity course ES6 - JavaScript Improved

This is an Intermediate skill level course which takes approximately 4 weeks to complete and is offered for FREE!

| Lesson 1 | Lesson 2 | Lesson 2.5 | Lesson 3 | Lesson 3.5 | Lesson 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Syntax | Functions | Classes | Built-ins | Built-ins Pt2 | Professional Developer-fu |

12. Class Preview

Here’s a quick peek of what a JavaScript class look like:

class Dessert {

constructor(calories = 250) {

this.calories = calories;

}

}

class IceCream extends Dessert {

constructor(flavor, calories, toppings = []) {

super(calories);

this.flavor = flavor;

this.toppings = toppings;

}

addTopping(topping) {

this.toppings.push(topping);

}

}

Notice the new class keyword right in front of Dessert and IceCream, or the new extends keyword in class IceCream extends Dessert? What about the call to super() inside the IceCream’s constructor() method.

There are a bunch of new keywords and syntax to play with when creating JavaScript classes. But, before we jump into the specifics of how to write JavaScript classes, we want to point out a rather confusing part about JavaScript compared with class-based languages.

13. JavaScript’s Illusion of Classes

Classes in JavaScript can be a bit confusing if you think about how classes work in other languages but the general concept is all the same.

In other languages we use classes to create objects and provide inheritance. But JavaScript isn’t like that exactly. In JavaScript we use functions to create objects.

var cookie = new Desert();

So when we create a new Dessert() like above, Dessert() is just a regular function.

Being able to inherit data and functionality (properties and methods) in JavaScript happens through prototypal inheritance.

Just because ECMAScript has provided us with the following new keywords

classsuperextends

It doesn’t mean the entire way the language works has changed.

JavaScript still uses functions and prototypal inheritance under the hood. We just have a new cleaner way to write the same functionality.

Just keep in mind that the underlying functionality of the language hasn’t changed. That said,

- JavaScript is not a class-based language

- It uses functions to create objects

- It links objects together by prototypal inheritance

In other words, JavaScript classes are just a thin mirage over regular functions and prototypal inheritance.

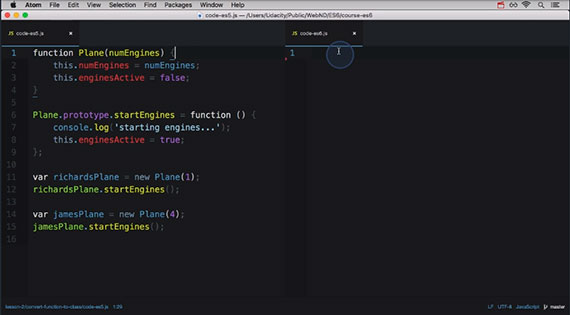

14. ES5 vs ES6 Classes

ES5 “Class” Recap

Since ES6 classes are just a mirage and hide the fact that prototypal inheritance is actually going on under the hood, let’s quickly look at how to create a “class” with ES5 code:

// ES5 Sytnax

function Plane(numEngines) {

this.numEngines = numEngines;

this.enginesActive = false;

}

// methods "inherited" by all instances

Plane.prototype.startEngines = function () {

console.log('starting engines...');

this.enginesActive = true;

};

const richardsPlane = new Plane(1);

richardsPlane.startEngines();

const jamesPlane = new Plane(4);

jamesPlane.startEngines();

In the code above, the Plane function is a constructor function that will create new Plane objects. The data for a specific Plane object is passed to the Plane function and is set on the object.

Methods that are “inherited” by each Plane object are placed on the Plane.prototype object. Then richardsPlane is created with one engine while jamesPlane is created with 4 engines.

Both objects, however, use the same startEngines method to activate their respective engines.

Things to note:

- the constructor function is called with the

newkeyword - the constructor function, by convention, starts with a capital letter

- the constructor function controls the setting of data on the objects that will be created

- “inherited” methods are placed on the constructor function’s prototype object

Keep these in mind as we look at how ES6 classes work because, remember, ES6 classes set up all of this for you under the hood.

ES6 Classes

Here’s what that same Plane class would look like if it were written using the new class syntax:

// ES6 Syntax

class Plane {

constructor(numEngines) {

this.numEngines = numEngines;

this.enginesActive = false;

}

startEngines() {

console.log('starting engines…');

this.enginesActive = true;

}

}

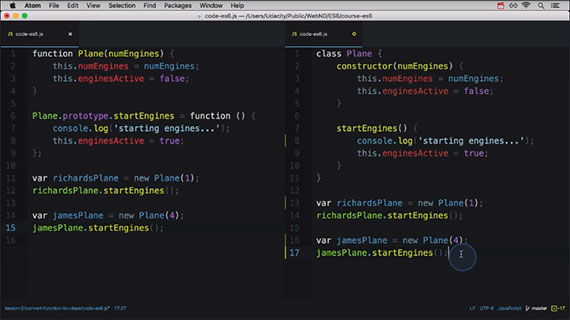

15. Converting a Function to a Class

Before

Let’s convert this function into a class.

// ES5 Syntax

function Plane(numEngines) {

this.numEngines = numEngines;

this.enginesActive = false;

}

Plane.prototype.startEngines = function () {

console.log('starting engines...');

this.enginesActive = true;

}

var richardsPlane = new Plane(1);

richardsPlane.startEngines();

var jamesPlane = new Plane(4);

jamesPlane.startEngines();

Everything inside the constructor function is now placed inside a method with the name constructor.

// ES6 Syntax

class Plane {

constructor(numEngines) {

this.numEngines = numEngines;

this.enginesActive = false;

}

}

This constructor method will automatically run when a new object is constructed from this class. If any data is needed to create the object then it needs to be included here.

So this takes care of creating an object. Now the methods that all objects inherit are placed inside the class.

// ES6 Syntax

class Plane {

constructor(numEngines) {

this.numEngines = numEngines;

this.enginesActive = false;

}

startEngines() {

console.log('starting engines...');

this.enginesActive = true;

}

}

startEngines() exists on the prototype explicitly in the pre-class way of writing it. Now it appears inside the class but the functionality is exactly the same.

Also it looks like startEngines() and this constructor() method are the same kind of method but the constructor method is not on the prototype. It’s a new special method that

exists in a class and is used to initialize new objects.

To drive this home, the functionality of these two is exactly the same. The class syntax is just a nicer way of writing it. In fact, we create new objects in exactly the same way with this new class syntax.

// ES6 Syntax

class Plane {

constructor(numEngines) {

this.numEngines = numEngines;

this.enginesActive = false;

}

startEngines() {

console.log('starting engines...');

this.enginesActive = true;

}

}

var richardsPlane = new Plane(1);

richardsPlane.startEngines();

var jamesPlane = new Plane(1);

jamesPlane.startEngines();

If you already understand prototypal inheritance then you already have a good understanding of how class and class methods work.

After

16. Working with JavaScript Classes

Just to prove that there isn’t anything special about class, check out this code:

class Plane {

constructor(numEngines) {

this.numEngines = numEngines;

this.enginesActive = false;

}

startEngines() {

console.log('starting engines…');

this.enginesActive = true;

}

}

typeof Plane; // function

Returns: function

That’s right—it’s just a function! There isn’t even a new type added to JavaScript.

⚠️ Where Are All The Commas? ⚠️

Did you notice that there aren’t any commas between the method definitions in the Class? Commas are not used to separate properties or methods in a Class. If you add them, you’ll get a

SyntaxErrorofunexpected token ,.

Quiz Question

Take a look at the following code:

class Animal {

constructor(name = 'Sprinkles', energy = 100) {

this.name = name;

this.energy = energy;

}

eat(food) {

this.energy += food / 3;

}

}

Which of the following are true?

- the

eat()method ends up onAnimal.prototype - typeof Animal === ‘class’

- typeof Animal === ‘function’

Solution

Options 1 and 3 are both true. Methods that appear in the class definition are placed on that class’s prototype object and a class is just a function.

- Option 1 is correct. Methods that appear in the class definition are, under the hood, placed on that class’s prototype object.

- Option 2 is not correct. A class is actually just a function.

- Option 3 is correct. A class is a function.

Static methods

To add a static method, the keyword static is placed in front of the method name. Look at the badWeather() method in the code below.

class Plane {

constructor(numEngines) {

this.numEngines = numEngines;

this.enginesActive = false;

}

static badWeather(planes) {

for (plane of planes) {

plane.enginesActive = false;

}

}

startEngines() {

console.log('starting engines…');

this.enginesActive = true;

}

}

See how badWeather() has the word static in front of it while startEngines() doesn’t? That makes badWeather() a method that’s accessed directly on the Plane class, so you can call it like this:

Plane.badWeather([plane1, plane2, plane3]);

NOTE: A little hazy on how constructor functions, class methods, or prototypal inheritance works? We’ve got a course on it! Check out Object Oriented JavaScript.

Benefits of classes

- Less setup

- There’s a lot less code that you need to write to create a function

- Clearly defined constructor function

- Inside the class definition, you can clearly specify the constructor function.

- Everything’s contained

- All code that’s needed for the class is contained in the class declaration. Instead of having the constructor function in one place, then adding methods to the prototype one-by-one, you can do everything all at once!

Things to look out for when using classes

classis not magic- The

classkeyword brings with it a lot of mental constructs from other, class-based languages. It doesn’t magically add this functionality to JavaScript classes.

- The

classis a mirage over prototypal inheritance- We’ve said this many times before, but under the hood, a JavaScript class just uses prototypal inheritance.

- Using classes requires the use of

new- When creating a new instance of a JavaScript class, the

newkeyword must be used

- When creating a new instance of a JavaScript class, the

For example,

class Toy {

// some class code

}

const myToy1 = Toy(); // throws an error

Uncaught TypeError: Class constructor Toy cannot be invoked without ‘new’

const myToy2 = new Toy(); // this works!

17. Super and Extends

Now that we’ve looked at creating classes in JavaScript. Let’s use the new super and extends keywords to extend a class.

// ES6 --------------------------------------

class Tree {

constructor(size = '10', leaves = {

spring: 'green',

summer: 'green',

fall: 'orange',

winter: null}) {

this.size = size;

this.leaves = leaves;

this.leafColor = null;

}

changeSeason(season) {

this.leafColor = this.leaves[season];

if (season === 'spring') {

this.size += 1;

}

}

}

class Maple extends Tree {

constructor(syrupQty = 15, size, leaves) {

super(size, leaves);

this.syrupQty = syrupQty;

}

changeSeason(season) {

super.changeSeason(season);

if (season === 'spring') {

this.syrupQty += 1;

}

}

gatherSyrup() {

this.syrupQty -= 3;

}

}

const myMaple = new Maple(15, 5);

myMaple.changeSeason('fall');

myMaple.gatherSyrup();

myMaple.changeSeason('spring');

Both Tree and Maple are JavaScript classes. The Maple class is a “subclass” of Tree and uses the extends keyword to set itself as a “subclass”.

To get from the “subclass” to the parent class, the super keyword is used. Did you notice that super was used in two different ways? In Maple’s constructor method, super is used as a function. In Maple’s changeSeason() method, super is used as an object!

Compared to ES5 subclasses

Let’s see this same functionality, but written in ES5 code:

// ES5 --------------------------------------

function Tree() {

this.size = size || 10;

this.leaves = leaves || {

spring: 'green', summer: 'green', fall: 'orange', winter: null

};

this.leafColor;

}

Tree.prototype.changeSeason = function(season) {

this.leafColor = this.leaves[season];

if (season === 'spring') {

this.size += 1;

}

}

function Maple (syrupQty, size, leaves) {

Tree.call(this, size, leaves);

this.syrupQty = syrupQty || 15;

}

Maple.prototype = Object.create(Tree.prototype);

Maple.prototype.constructor = Maple;

Maple.prototype.changeSeason = function(season) {

Tree.prototype.changeSeason.call(this, season);

if (season === 'spring') {

this.syrupQty += 1;

}

}

Maple.prototype.gatherSyrup = function() {

this.syrupQty -= 3;

}

const myMaple = new Maple(15, 5);

myMaple.changeSeason('fall');

myMaple.gatherSyrup();

myMaple.changeSeason('spring');

Both this code and the class-style code above achieve the same functionality.

18. Extending Classes from ES5 to ES6

Let’s hide the inner workings of these classes to compare how they’re constructed.

// ES5 --------------------------------------

function Tree(size, leaves) {...}

Tree.prototype.changeSeason = function (season) {...}

function Maple(syrupQty, size, barkColor, leaves) {...}

Maple.prototype = Object.create(Tree.prototype);

Maple.prototype.constructor = Maple;

Maple.prototype.changeSeason = function (season) {...}

Maple.prototype.gatherSyrup = function () {...}

// ES6 --------------------------------------

class Tree {

constructor(size = '10', leaves = {...}) {...}

changeSeason(season) {...}

}

class Maple extends Tree {

constructor(syrupQty = 15, size, leaves) {...}

changeSeason(season) {...}

gatherSyrup() {...}

}

Remember that there’s a new special method called the constructor() that’s run whenever the class is called. It’s doing the same thing as the Tree constructor in ES5.

Also remember that a method inside of a class definition (changeSeason) is the same as adding that method to the prototype. That takes care of the base class which looks pretty similar to before.

The bigger difference comes when extending the base class with a subclass. With the older ES5 code we’d have to:

- Create another constructor function

- Then set the function’s prototype to the base class’ prototype

- Since we’ve overwritten the original prototype object, we need to set/reset the connection between the constructor property and the original constructor function.

Then we’re back to the normal routine of adding methods to the prototype object.

Now compare all of the code it took to get these two functions connected and prototype linked in ES5 to the class code of ES6.

It’s just another class definition but it uses the extends keyword to connect the Maple class to the base class Tree.

Significantly nicer right? It’s also a lot easier to call the base class from the subclass.

The es6 code uses the new super keyword while you have to use .call in the es5 code and pass this as the first argument.

Also, calling a prototype method also takes a lot less code in the new class format too.

19. Working with JavaScript Subclasses

Like most of the new additions, there’s a lot less setup code and it’s a lot cleaner syntax to create a subclass using class, super, and extends.

Just remember that, under the hood, the same connections are made between functions and prototypes.

super must be called before this

In a subclass constructor function, before this can be used, a call to the super class must be made.

class Apple {}

class GrannySmith extends Apple {

constructor(tartnessLevel, energy) {

this.tartnessLevel = tartnessLevel; // `this` before `super` throws an error!

super(energy);

}

}

Question 1 of 2

Take a look at the following code:

class Toy {}

class Dragon extends Toy {}

const dragon1 = new Dragon();

Given the code above, is the following statement true or false?

dragon1 instanceof Toy;

- true

- false

Solution

The dragon1 variable is an object created by the Dragon class, and since the Dragon class extends the Toy class, dragon1 is also considered an instance of Toy.

- true

Question 2 of 2

Let’s say that a Toy class exists and that a Dragon class extends the Toy class.

What is the correct way to create a Toy object from inside the Dragon class’s constructor method?

- super();

- super.call(this)

- parent();

- Toy();

Solution

Option 1 is the correct way to call the super class from within the subclass’s constructor function.

- super();

20. Quiz: Building Classes & Subclasses

Directions

Create a Bicycle subclass that extends the Vehicle class. The Bicycle subclass should override Vehicle’s constructor function by changing the default values for wheels from 4 to 2 and horn from 'beep beep' to 'honk honk'.

Code

/*

* Programming Quiz: Building Classes and Subclasses (2-3)

*/

class Vehicle {

constructor(color = 'blue', wheels = 4, horn = 'beep beep') {

this.color = color;

this.wheels = wheels;

this.horn = horn;

}

honkHorn() {

console.log(this.horn);

}

}

// your code goes here

/* tests

const myVehicle = new Vehicle();

myVehicle.honkHorn(); // beep beep

const myBike = new Bicycle();

myBike.honkHorn(); // honk honk

*/

Solution

/*

* Programming Quiz: Building Classes and Subclasses (2-3)

*/

class Vehicle {

constructor(color = 'blue', wheels = 4, horn = 'beep beep') {

this.color = color;

this.wheels = wheels;

this.horn = horn;

}

honkHorn() {

console.log(this.horn);

}

}

// your code goes here

class Bicycle extends Vehicle {

constructor(color, wheels = 2, horn = 'honk honk') {

super(color, wheels, horn);

this.horn = horn;

}

honkHorn() {

super.honkHorn();

}

}

/* tests

const myVehicle = new Vehicle();

myVehicle.honkHorn(); // beep beep

const myBike = new Bicycle();

myBike.honkHorn(); // honk honk

*/

21. Leason 2 Summary

In this lesson we covered a new way to write functions - the arrow function. We also looked at how you can you default function parameters to pass default values to functions. Finally, we wrapped it up with JavaScript classes (simulated through functions)

In the next lesson we’ll explore the latest set of built-in that are available through JavaScript.