React & Redux

<– back to React Nanodegree homepage

1. Managing State

1.1 Introduction

Welcome to Udacity’s Redux course. The goal of this course is to help you learn how to more effectively manage state in your applications. As a byproduct of that, you’ll have to learn Redux along the way.

Now, you may find this course a little slow. That’s on purpose. The reason we’re going to take it slow is because historically Redux is pretty difficult to learn.

The problem isn’t necessarily Redux itself, but everything else that you typically pair with Redux.

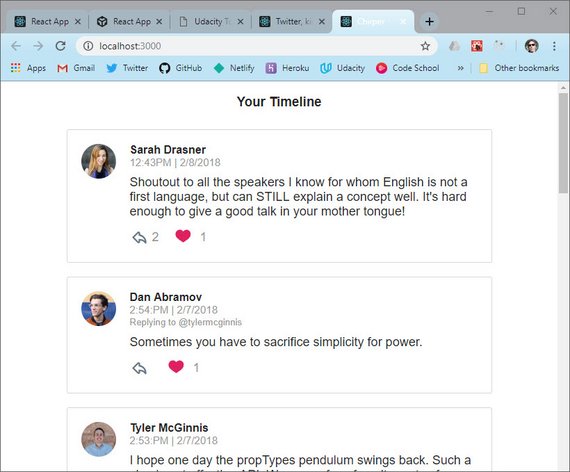

What happens is traditionally when you learn Redux, you also learn it alongside

- React

- React-Router

- React-Redux bindings

- and a few other helper libraries

This causes all sorts of issues because your brain has a hard time separating what’s what.

To fix this, we’re going to take a slow gradual approach.

- We’ll start off by looking at just Redux, nothing else.

- Once you’ve mastered Redux itself, we’ll add in some basic UI with just HTML and JavaScript.

- Then, when you’re feeling comfortable with hooking up Redux to a simple UI, we’ll swap out that UI for React, and you’ll learn how the two work together.

- We’ll then look at some common pain points when combining React and Redux, and we’ll learn how the React-Redux bindings help solve these pain points.

- Finally, we’ll use Create React App to see how a real-world React and Redux app is built.

Now, we’re covering quite a lot, but remember we’re going to take it slow and go step-by-step.

1.1.1 Lesson Roadmap

Since Redux is not a topic for beginners and can be a daunting area to break into. We’ve broken down your path to learning Redux into the following lessons:

- Lesson 1 - Managing State

- Lesson 2 - UI + Redux

- Lesson 3 - Redux Middleware

- Lesson 4 - Redux with React

- Lesson 5 - Asynchronous Redux

- Lesson 6 - react-redux

- Lesson 7 - Real World Redux

Lesson 1 - Managing State

You’ll learn techniques to make your state more predictable by moving your state to a central location and establishing strict rules for getting, listening, and updating that state.

Lesson 2 - UI + Redux

You’ll learn to move away from having state live in the DOM by creating a vanilla JavaScript application whose state is managed entirely by Redux.

Lesson 3 - Redux Middleware

You’ll learn to create custom middleware and add it to your Redux store. This middleware will allow you to enhance your store by hooking into and intercepting actions before they reach any reducers.

Lesson 4 - Redux with React

You’ll learn how to add React to a Redux application and have the state of that application be managed by Redux.

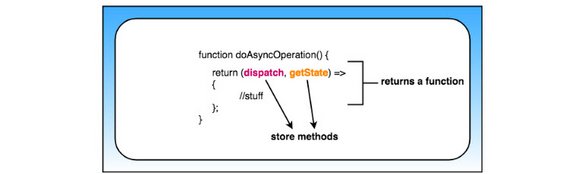

Lesson 5 - Asynchronous Redux

You’ll learn to better abstract asynchronous events by creating your own custom Thunk middleware and adding it to your store.

Lesson 6 - react-redux

You’ll learn to leverage the react-redux bindings in order to leverage the benefits of a UI library like React and a state management library like Redux.

Lesson 7 - Real World Redux

You’ll take your knowledge of Redux and utilize it by building a real world Redux application. You’ll also learn advanced Redux topics like reducer composition and normalization.

1.2 The Store

Think about any application you’ve ever made. Most likely that app was composed of two things, UI and state.

Now, think of any bug you’ve ever had. Odds are that bug was caused by state mismanagement. Your application was expecting the state to be one thing, but it was actually something else.

When your computer freezes and you have to restart it, that’s because some state inside of your computer got to a weird place. By restarting it, you reset that state. When a website says you have a new notification, but you click on that and there’s nothing new, that’s because the state of the app was mismanaged.

As was said previously, the goal of this course is to make state management, on any app you build, more predictable. One of the best ways to improve the quality of the apps you build is to improve the predictability of the state in an application.

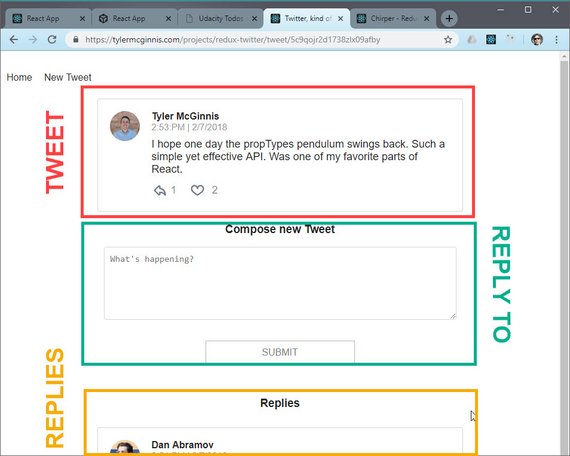

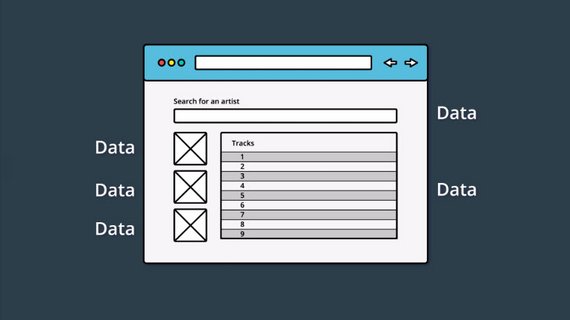

1.2.1 App Data

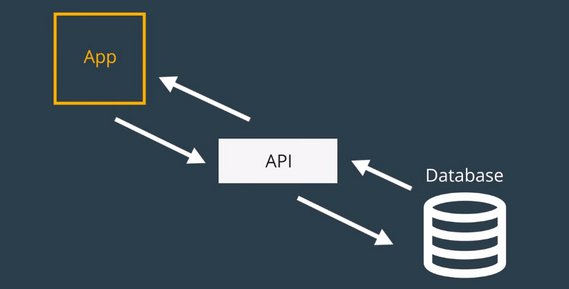

A traditional app might look something like this:

App data is sprinkled throughout the app.

Notice in the image above, that this simple application has a lot of state:

- There are the images in the sidebar on the left.

- There are rows of tracks in the main area.

- Each Track will have its own information that it’s maintaining.

- There’s the search field at the top that introduces new state to the app (the searched for artist/track information).

And this is just one, simple page of this application. In most sites you use, there is information littered throughout every single page of the entire app.

Remember that the main goal of Redux is to make the state management of an application more predictable. Let’s see what that might look like:

Application data is just referenced by the app.

In this example, the app appears exactly the same to the end user, however, it’s functioning quite differently under the hood. All of the data is stored outside of the UI code and is just referenced from the UI code.

With a change like this, if the data needs to be modified at all, then all of the data is located in one place and needs to be only changed once. Then the areas of the app that are referencing pieces of data, will be updated since the source they’re pulling from has changed.

1.2.2 State Tree

One of the key points of Redux is that all of the data is stored in a single object called the state tree. But what does a state tree actually look like? Good question! Here’s an example:

{

recipes: [

{ … },

{ … },

{ … }

],

ingredients: [

{ … },

{ … },

{ … },

{ … },

{ … },

{ … }

],

products: [

{ … },

{ … },

{ … },

{ … }

]

}

See how all of the data for this imaginary cooking site is stored in a single object? So all of the state (or “application data”) for this site is stored in one, single location. This is what we mean when we say “state tree”…it’s just all of the data stored in a single object.

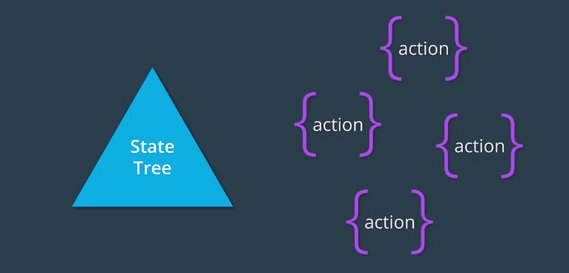

Throughout this course, whenever we refer to an application’s “state tree”, we’ll use a triangle to convey this concept.

Now that we’ve decided we’re going to put all of our state into a single location called the state tree, the next thing we need to figure out, is how we’ll actually interact with it.

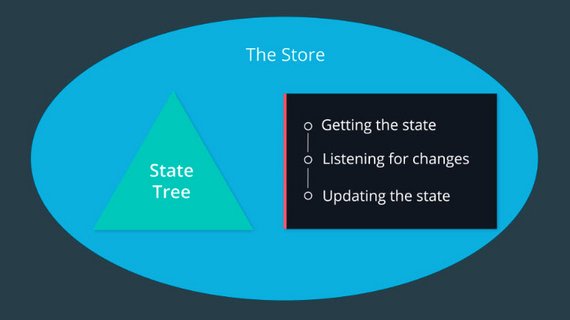

If we’re actually going to build a real application with our state tree, there are three ways in which we’ll need to interface with it.

- First, we’ll need a way of getting the state.

- Second, we’ll need a way to listen for when the state changes.

- Third, we’ll need a way to update the state.

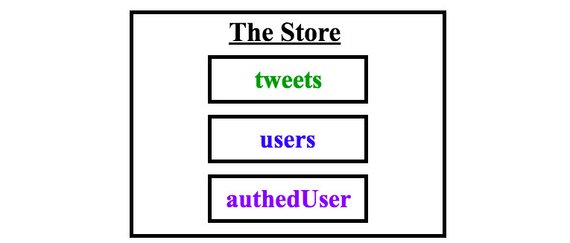

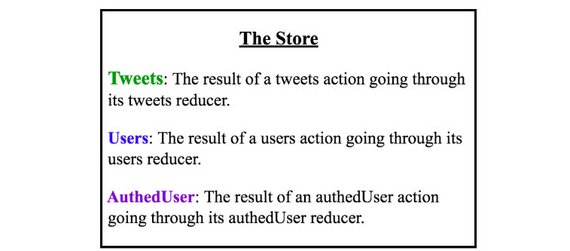

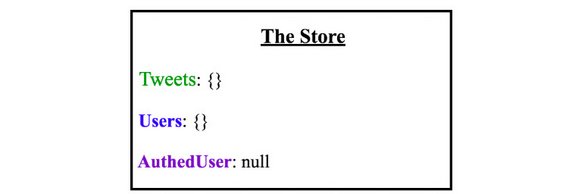

Let’s go ahead and wrap all of these things together into a single concept called the store.

So, when we talk about the store, we’re talking about the state tree as well as three ways in which we’ll interact with it

- Getting the state

- Listening for updates to the state

- Updating the state

1.2.3 Quiz Question

What are the ways we can interact with the state tree?

- Getting changes from the state

- Listening for changes from the state

- Updating the state

1.2.4 Summary

Summary In this lesson, we looked at the data in an application. We saw that in traditional apps, the data is mixed in with the UI and markup. This can lead to hard-to-find bugs where updating the state in one location doesn’t update it in every location.

We learned that the main goal that Redux is trying to offer is predictable state management. The way that Redux tries to accomplish this is through having a single state tree. This state tree is an object that stores the entire state for an application. Now that all state is stored in one location, we discovered three ways to interact with it:

- getting the state

- listening for changes to the state

- updating the state

Then we combine the three items above and the state tree object itself into one unit which we called the store. We’ll look at creating this store in the next lesson.

1.3 Getting State & Listening for Changes

In this section, we’ll be building the store. If you remember from the previous section, the store has the following information:

- the state tree

- a way to get the state tree

- a way to listen and respond to the state changing

- a way to update the state

1.3.1 Create Store from Scratch

So this is what we’re going to do in this lesson - we’re going to actually create the store code ourselves, from scratch.

In the following video, we’ll start with a blank index.js file and create a factory function that creates store objects. Then we’ll have the store keep track of the state, and we’ll write the method to get the state from the store.

Pop open your code editor, and let’s get started!

function createStore() {

// The store should have four parts

// 1. The state

// 2. Get the state

// 3. Listen to changes on the state

// 4. Update the state

let state

const getState = () => state;

return {

getState

}

}

We started building out the createStore function. Currently, this factory function:

- takes in no arguments

- sets up a local (private) variable to hold the state

- sets up a

getState()function - returns an object that publicly exposes the

getState()function

Let’s take a look at the getState() function

1.3.2 Question 1 of 5

Thinking about the code we just wrote, what does the

getState()function do?

- It modifies the existing state variable.

- It logs who access the state variable.

- It returns the existing state variable

- It formats the state object for easy parsing.

Our list of things we need to build for the store is shrinking:

-

the state tree -

a way to get the state tree - a way to listen and respond to the state changing

- a way to update the state

Our next task on the list is to make a way to listen for changes to the state.

function createStore() {

// The store should have four parts

// 1. The state

// 2. Get the state

// 3. Listen to changes on the state

// 4. Update the state

let state;

let listeners = [];

const getState = () => state;

const subscribe = listener => {

listeners.push(listener);

};

return {

getState,

subscribe

};

}

Here’s an example of how we would use our createStore() function by creating two listeners.

// Sample implementation

const store = createStore();

store.subscribe(() => {

console.log('The new state is: ', store.getState());

})

store.subscribe(() => {

console.log('The store changed');

})

Next we want to provide the user a way to unsubscribe for changes. We do this by returning a function that when invoked, filters out the listener from our array of listeners.

function createStore() {

// The store should have four parts

// 1. The state

// 2. Get the state

// 3. Listen to changes on the state

// 4. Update the state

let state;

let listeners = [];

const getState = () => state;

const subscribe = listener => {

listeners.push(listener);

return () => {

listeners = listeners.filter(l => l !== listener);

};

};

return {

getState,

subscribe

};

}

Here’s an example of how we would use our updated createStore() function with the same two listeners except now the second one is assigned to an unsubscribe constant that when invoked, removes the listener from the store.

// Sample implementation

const store = createStore();

store.subscribe(() => {

console.log('The new state is: ', store.getState());

})

const unsubscribe = store.subscribe(() => {

console.log('The store changed');

})

unsubscribe();

1.3.3 Question 2 of 5

Which of the following is true about

store.subscribe()?

- It is a function.

- When called, it is passed a single function.

- When called, it is passed multiple functions.

- It modifies the internal state tree variable.

- It invokes the function that was passed to it.

- It returns an Array of listener functions.

- It returns a function.

let’s review the functionality has so far.

- First, it contains the state,

- next, it has a

getState()function, which just returns us the state, - and finally,it has a subscribe function, which will let each of the listeners know whenever the state changes.

If you remember back to when we first talked about our store, there were four parts.

- The state

- getting the state

- listening to changes on the state

- updating the state

As of right now, we have three of the four.

So let’s add in that fourth piece updating the state.

Now remember, the whole goal here is to increase the predictability of the state in our application. We can’t just allow anything or anyone to update the state. If we did, that would drastically decrease predictability.

In fact, the only way in which we can increase predictability in terms of updating the state, is by establishing a strict set of rules for how updates can be made.

NFL Analogy

Let’s look at an NFL team for example. In order for a team to maximize their chances of winning, they always have to be on the same page. They need to operate as one cohesive unit. Every miscommunication can and will lead to negative consequences.

So in a sense, NFL teams have the same goals that we do. Increasing predictability. But how do they go about accomplishing this?

Well, they create a Playbook, and each player must know it by heart. This way, when the team runs a play from the playbook, players will know exactly what each member of the team will be doing. Maximizing predictability.

Can we take the same idea and apply it to our applications? Well, we can, and it’s so fundamental that we’ll call it rule number one to increasing predictability. Just like NFL teams have a collection of plays, we too can have a collection of events that can occur in our app which will change the state of our store.

We’ve got our first rule!

Rule #1 - Only an event can change the state of the store.

Ok…well, without knowing what an “event” is, this rule is less than helpful :-\ Fear not, because we’re going to look at what events are next:

1.3.4 TO-DO Example

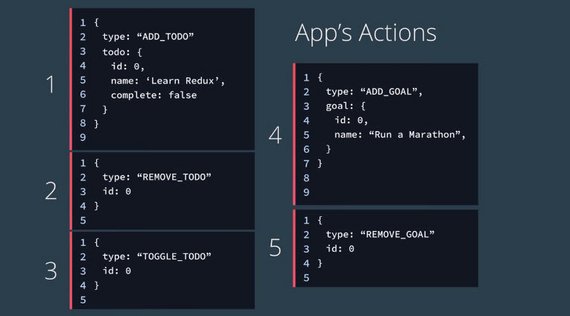

Previously, you were introduced to Rule #1 for increasing the predictability of state within the store: Have a collection of events that can occur in the application which will change the state of the store.

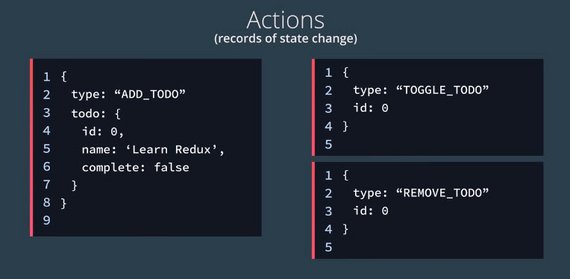

Now, what does this actually look like? Let’s say we were building a to-do list app. One event that would change the state of the store would be when the user adds a new item to their to-do list.

How might we go about representing that as an event? What if we just use an object with a type property that describes the event taking place? So in our example, that object might look like this.

It’s just a plain object with a type property that indicates what type of event occurred.

Now, we could add any information we want into the event just by adding an additional property to the object. The add to-do event took place but what was the to-do that was actually added?

We can add a to-do property and include the to-do’s name and information.

If I delete that to do, what event might this be?

Well, I would probably label it a REMOVE_TODO event.

And how do we know which to do was removed?

We’ll pass along the to-do items id.

Similarly, marking an item as “completed” would toggle its state. This event of toggling the state might include an id property along with the type property.

So, we have these objects that record the events that have happened. Let’s give a name to these objects, we’ll call them “actions” because they’re the type of actions which can occur in the app which will change the application state.

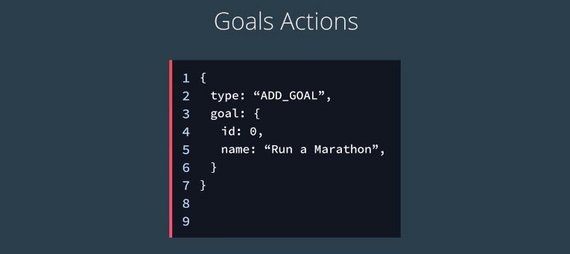

Now, what if we wanted to add another feature to our app?

Let’s say instead of just adding short-term to-do items, we also wanted the user to be able to add long-term goals.

The action for adding a goal might look something like this.

Notice that the type property is ADD_GOAL, and a goal property is being passed along.

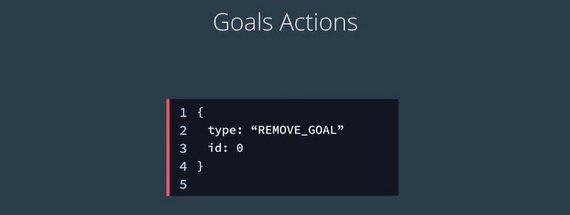

And just like deleting a to-do, we need an action to represent the event of deleting a goal.

See how descriptive that is? We will never be able to confuse this action with the removed to do actions.

All actions must have a type property. Now, what we’ve done is we’ve created a collection of all of the actions which can change the state of our app.

If the state of our app changes, we’ll know that one of those actions occurred.

1.3.5 Shopping Cart Example

When an event takes place in a Redux application, we use a plain JavaScript object to keep track of what the specific event was. This object is called an Action.

Let’s take another look at an Action:

{

type: "ADD_PRODUCT_TO_CART"

}

As you can see, an Action is clearly just a plain JavaScript object.

What makes this plain JavaScript object special in Redux, is that every Action must have a type property.

The purpose of the type property is to let our app (Redux) know exactly what event just took place. This Action tells us that a product was added to the cart. That’s incredibly descriptive and quite helpful, isn’t it?

Now, since an Action is just a regular object, we can include extra data about the event that took place:

{

type: "ADD_PRODUCT_TO_CART",

productId: 17

}

In this Action, we’re including the productId field. Now we know exactly which product was added to the store!

One more note to keep in mind as you build your Action objects: it’s better practice to pass as little data as possible in each action. That is, prefer passing the index or ID of a product rather than the entire product object itself.

Action Creators are functions that create/return action objects. For example:

// ES6

const addItem = item => ({

type: ADD_ITEM,

item

});

// ES5

var addItem = function addItem(item) {

return {

type: ADD_ITEM,

item: item

};

};

1.3.6 Question 3 of 5

Is it true that every Action must have a

typeproperty?

- Yes - Redux will throw an error if missing

- No

1.3.7 Question 4 of 5

Can an Action have three or more fields?

- Yes - There’s no limit but it’s best to keep objects as light as possible

- No

1.3.8 Question 5 of 5

Consider each

// A const receivePost = post => ({ type: RECEIVE_POST, post });// B const receivePost = post => ({ type: RECEIVE_POST, post: post });// C const clearErrors = { type: CLEAR_ERRORS };// D const addSeven = { type: 'ADD_NUMBER', number: 7 };// E const removeComments = { comments: null };Which of the above are valid actions?

- A

- B

- C

- D

- E

1.3.9 Summary

In this section, we started creating our store by building out a createStore() function. So far, this function keeps track of the state, and provides a method to get the state and one to keep track of listener functions that will be run whenever the state changes.

In the next section, we’ll add a method to handle updating the state.

1.4 Updating State

Let’s step back one more time and think about what Redux is all about. The whole goal of Redux is to increase predictability:

Redux is a predictable state container for JavaScript apps.

With this in mind, let’s see dig into how we can use actions and our state tree to predictably manage an application’s state.

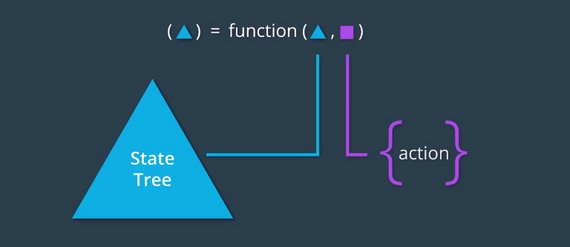

We have the entire state of the application in the state tree. We also know about every action that can change the application state. So we have these two distinct pieces of data, but we need something to tie them together.

Meaning, we need a way to update our state based on the current action which occurred.

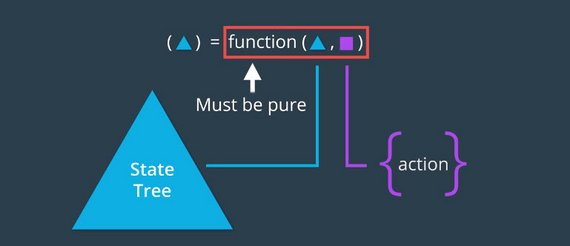

What if we just used a function to do this? We could have that function taking two arguments, the current state, and the action which occurred. Then, based off of that action, this function would be responsible for returning the new updated state.

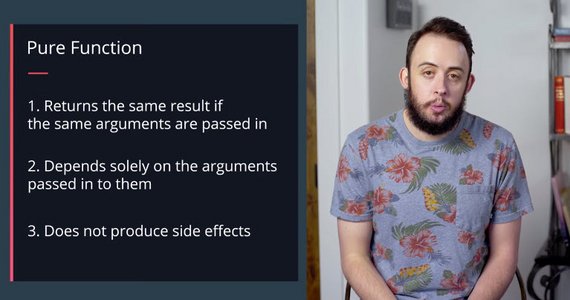

That sounds pretty good but we can’t forget that the whole goal here is predictability. This function has to be as predictable as possible. But, what does that actually mean?

We should be able to know what the return value will be of the function based on the input values.

Now this sounds complicated but it turns out that the functional programming community has already solved this problem and they’ve given it a name. It’s called pure functions.

This brings us to rule number two for increasing predictability.

The function that returns the new state needs to be a pure function.

So far, our rules are:

- Only an event can change the state of the store.

- The function that returns the new state needs to be a pure function.

A pure function can be a bit theoretical, so we’ll take it step by step and explain why a pure function is so powerful and how it helps improve predictability.

1.4.1 What are Pure Functions

Pure functions are integral to how state in Redux applications is updated. By definition, pure functions:

- Return the same result if the same arguments are passed in

- Depend solely on the arguments passed into them

- Do not produce side effects, such as API requests and I/O operations

Let’s check out an example of a pure function, square():

// `square()` is a pure function

const square = x => x * x;

square() is a pure function because it outputs the same value every single time, given that the same argument is passed into it. There is no dependence on any other values to produce that result, and we can safely expect just that result to be returned – no side effects (more on this in a bit!).

On the other hand, let’s check out an example of an impure function, calculateTip():

// `calculateTip()` is an impure function

const tipPercentage = 0.15;

const calculateTip = cost => cost * tipPercentage;

calculateTip() calculates and returns a number value. However, it relies on a variable (tipPercentage) that lives outside the function to produce that value. Since it fails one of the requirements of pure functions, calculateTip() is an impure function. However, we could convert this function to a pure function by passing in the outside variable, tipPercentage, as a second argument to this function!

const calculateTip = (cost, tipPercentage = 0.15) => cost * tipPercentage;

1.4.2 Why Pure Functions Are Great

For our purposes, the most important feature of a pure function is that it’s predictable. If we have a function that takes in our state and an action that occurred, the function should (if it’s pure!) return the exact same result every single time.

You’re going to be sick of this by the end ;-) but this course (and Redux!) are all about predictability!

1.4.3 Question 1 of 4

What is true about pure functions? Check all that apply.

- Pure functions do not rely on information other than the arguments passed in to them to generate an outputs

- Pure functions can produce different outputs even with the same arguments passed in each time.

- Pure functions do not depend on external state

- Pure functions are expected to modify shared state

- Pure functions should modify the original arguments passed into them

1.4.4 Question 2 of 4

Which of the following are pure functions? Please check all that apply:

Math.random();const add = (a, b) => ( a + b );Date.now();const addAndPrint = (a, b) => ( const sum = a + b; console.log(`The sum is : ${sum}`); return sum; );const double = array => ( let doubleArray = []; array.forEach(n => doubleArray.push(n * 2)); return doubleArray; );

1.4.5 Todos App

Now, back in our Todos app, what we need is a way update the internal state of our store based on the specific action that occurred.

The way we do this is by creating a function (called a reducer) that takes two arguments.

- state - which is the internal state inside our store

- action - an object with a

typeproperty that describes the action.

For this to work properly the function needs to be a pure function. This means that it cannot directly mutate any of the data in the state object or array.

The function takes the state and the action and then returns a new copy of state with any changes made.

Our reducer will be called todos since this is a Todos app. It will listen for a specific event type and then create a new state object which it returns in response to that event. If no match is made it returns the state unchanged.

// reducer

function todos(state = [], action) {

if (action.type === 'ADD_TODO') {

return state.concat([action.todo]);

}

return state;

}

In this case we add the todo item directly onto our state array using the concat method which is a non-mutating method. It returns a new array.

Here is how we would call the todos reducer function and what the arguments would consist of.

// state array & action object

state = [];

action = {

type: 'ADD_TODO',

todo: { id: 0, name: 'Learn Redux', completed: false }

};

// call to reducer

const newState = todos(state, action);

console.log(newState); // [ { id: 0, name: 'Learn Redux', completed: false } ]

So, this gives us a preview into how we will be updating the state from our createStore function.

Now all we need to do is invoke our todos function (parsing current state as well as the action that occurred) to get the new state.

One other thing to note is that we are using ES6’s new default value for state. This is in case we don’t have a state object it will start out as an empty array.

This function is called a reducer because it follows the Array.prototype.reduce format of taking the state, an action, and then reducing that to a brand new state.

So, going back to this visual, the function here is a reducer since it takes in the state and an action, and returns the new state.

A reducer must ALWAYS be a pure function.

1.4.6 Reducer Quiz

This quiz was crazy. It required reading the Reducers section of the Redux docs in order to figure out.

Here’s the instructions.

/* Create A Reducer

*

* You need to create a reducer called "appReducer" that accepts two arguments:

* - First, an array containing information about ice cream

* - Second, an object with a 'DELETE_FLAVOR' `type` key

* (i.e., the object contains information to delete the flavor from the state)

*

* The action your reducer will receive will look like this:

* { type: 'DELETE_FLAVOR', flavor: 'Vanilla' }

*

* And the initial state will look something like this:

* [{ flavor: 'Chocolate', count: 36 }, { flavor: 'Vanilla', count: 210 }];

*/

Given that we have the following:

- state:

[{ flavor: 'Chocolate', count: 36 }, { flavor: 'Vanilla', count: 210 }] - action:

{ type: 'DELETE_FLAVOR', flavor: 'Vanilla' }

Create a reducer that will return the new state.

function appReducer(state, action) {

if (typeof state === 'undefined') {

return [];

}

if (action.type === 'DELETE_FLAVOR') {

return Object.assign(

[],

state,

state.map(iceCream => {

if (iceCream.flavor === action.flavor) {

return Object.assign({}, iceCream, {

count: iceCream.count - 1

});

}

return iceCream;

})

);

}

return state;

}

This uses Object.assign() to create a new object/array (1st parameter) by copying the previous state (2nd parameter) and overwriting any keys/values/objects with the third & subsequent parameters.

The method signature is:

Object.assign(target, …sources)

Each subsequent source will overwrite the previous source. Also, this only performs a shallow copy. If the source value is a reference to an object, it only copies that reference value.

For deep cloning we must use an alternate method such as:

let obj3 = JSON.parse(JSON.stringify(obj1));.

1.4.7 Todos App continued

Reviewing what we have so far, there are three parts to the app.

- The actions represent the different events that will change the state of our store.

- The reducer is a function which takes in the current state and an action which occurred, and returns the new state.

- createStore is responsible for creating the actual store.

If you remember back to our implementation of createStore, so far we have three of the four parts.

- State Tree - as a

statevariable - Getting the state - we have a

getStatefunction - Listening for changes - we have a

subscribefunction - Updating the state

The last part we need to figure out, is how to update the state. To do that, we’ll create a new function called dispatch.

dispatch will be responsible for updating the state inside of our actual store.

To do that it needs to receive the action which is going to tell dispatch the specific event that occurred inside of the application.

const dispatch = action => {

state = todos(state, action);

listeners.forEach(listener => listener());

};

Now, with access to the state and to the action that occurred, dispatch can call our todos function passing it state and action and assign the result back to the state variable.

Next, because we just modified the state, we loop through the array of listener functions and invoke each one.

So, now whenever the user wants to update the state internally inside of our store, what they do is invoke dispatch, passing it the specific action which occurred.

1.4.8 Question 4 of 4

Match the following store methods.

Functionality Store Method gets the current state .getState() takes in functions that will be called when the state changes .subscribe() the application’s state the state tree modifies the state .dispatch()

1.4.9 Todos App add reducer function

We will now organize our app to better reflect the separation between library code and app code.

Library code would be our createStore() function and App code would be our todos function. We need to pass this function in to createStore().

Here’s what that would look like.

// Library code

function createStore(reducer) {

// The store should have four parts

// 1. The state

// 2. Get the state

// 3. Listen for changes on the state

// 4. Update the state

let state;

let listeners = [];

const getState = () => state;

const subscribe = listener => {

listeners.push(listener);

return () => {

listeners = listeners.filter(l => l !== listener);

};

};

const dispatch = action => {

state = reducer(state, action);

listeners.forEach(listener => listener());

};

return {

getState,

subscribe,

dispatch

};

}

Here’s what the App code would look like.

// App code

function todos(state = [], action) {

if (action.type === 'ADD_TODO') {

return state.concat([action.todo]);

}

return state;

}

const store = createStore(todos);

The new dispatch() method is pretty small, but is vital to our functioning store code. To briefly recap how the method functions:

dispatch()is called with an Action- the reducer that was passed to

createStore()is called with the current state tree and the action… this updates the state tree - because the state has (potentially) changed, all listener functions that have been registered with the

subscribe()method are called

1.4.10 Summary

In this section, we learned about a number of important points about Redux.

We learned about

- pure functions

- a Reducer function (which, itself, needs to be a pure function)

- dispatching changes in our store

- identifying which parts of our code are generic library code and which are specific to our app

1.5 Dispatching an Action

We now have the four parts of our store

- Internal state

- A way to get the state

- Listen for changes on the state

- Update the state

We also have a reducer function (todos) which specifies how the state will change based on the action that has ocurred in the application.

// Library code

function createStore(reducer) {

let state;

let listeners = [];

const getState = () => state;

const subscribe = listener => {

listeners.push(listener);

return () => {

listeners = listeners.filter(l => l !== listener);

};

};

const dispatch = action => {

state = reducer(state, action);

listeners.forEach(listener => listener());

};

return {

getState,

subscribe,

dispatch

};

}

// App code (reducer)

function todos(state = [], action) {

if (action.type === 'ADD_TODO') {

return state.concat([action.todo]);

}

return state;

}

Now we can create the store with the following.

// Create the store

const store = createStore(todos);

// subscribe to the listener

store.subscribe(() => {

console.log('The new state is: ', store.getState());

});

// dispatch an action

store.dispatch({

type: 'ADD_TODO',

todo: { id: 0, name: 'Learn Redux', complete: false }

});

We pass our reducer to createStore, subscribe a listener to be notified of change events, and dispatch an action.

What’s cool is now we can call dispatch as many times as we want. We do so by passing in the type and a new todo item which is added to the state.

So whenever we want to update the state of our store, all we need to do now is call dispatch add pass it the action which occurred.

We’ve finally finished creating the createStore function! Using the image above as a guide, let’s break down what we’ve accomplished:

- we created a function called

createStore()that returns a store object createStore()must be passed a “reducer” function when invoked- the store object has three methods on it:

.getState()- used to get the current state from the store.subscribe()- used to provide a listener function the store will call when the state changes.dispatch()- used to make changes to the store’s state- the store object’s methods have access to the state of the store via closure

1.5.1 QUIZ QUESTION

Which of the following are true statements about the store? Please select all that apply.

- Updates to the store can only be triggered by dispatching action.

- The

createStore()function is imported from React- The store’s subscribe() function helps connect React components to the store

- Updates to the store can only be triggered by overwriting the store object directly (i.e., without dispatching an action)

1.5.2 Summary

Up until this point, we’ve been building out the createStore() function, piece by piece. In this section, we put all of those pieces together to create a fully functioning project. Then we took that code and demoed it in the console.

We showed that subscribing to the store returned a function we could use to unsubscribe later. We also dispatched an action and saw how the state was updated as a result.

In the next section, we’ll keep building up our app-specific parts of the code to handle different actions and to be more error-proof.

1.6 Managing More Actions

As of right now, our code is handling the ADD_TODO action. There are still a couple more actions that our app is supposed to be able to handle:

- the REMOVE_TODO action

- the TOGGLE_TODO action

1.6.1 New Actions

Our app can not only handle adding todo items – it can now handle removing a todo item, as well as toggling a todo item (as complete or incomplete)! To make this all possible, we updated our todos reducer to be able to respond to actions of the type REMOVE_TODO and TOGGLE_TODO.

Before moving on, let’s make sure we’re on the same page on how this was all implemented. Our todos reducer originally looked like the following:

function todos (state = [], action) {

if (action.type === 'ADD_TODO') {

return state.concat([action.todo]);

}

return state;

}

To resolve additional action types, we added a few more conditions to our reducer logic:

function todos (state = [], action) {

if (action.type === 'ADD_TODO') {

return state.concat([action.todo]);

} else if (action.type === 'REMOVE_TODO') {

// ...

} else if (action.type === 'TOGGLE_TODO') {

// ...

} else {

return state;

}

}

Note that just like the original todos reducer, we simply return the original state if the reducer receives an action type that it’s not concerned with.

To remove a todo item, we called filter() on the state. This returns a new state (an array) with only todo items whose id’s do not match the id of the todo we want to remove:

function todos (state = [], action) {

if (action.type === 'ADD_TODO') {

return state.concat([action.todo]);

} else if (action.type === 'REMOVE_TODO') {

return state.filter((todo) => todo.id !== action.id);

} else if (action.type === 'TOGGLE_TODO') {

// ...

} else {

return state;

}

}

To handle toggling a todo item, we want to change the value of the complete property on whatever id is passed along on the action. We mapped over the entire state, and if todo.id matched action.id, we used Object.assign() to return a new object with merged properties:

function todos (state = [], action) {

if (action.type === 'ADD_TODO') {

return state.concat([action.todo]);

} else if (action.type === 'REMOVE_TODO') {

return state.filter((todo) => todo.id !== action.id);

} else if (action.type === 'TOGGLE_TODO') {

return state.map(todo =>

todo.id !== action.id

? todo

: Object.assign({}, todo, { complete: !todo.complete })

);

} else {

return state;

}

}

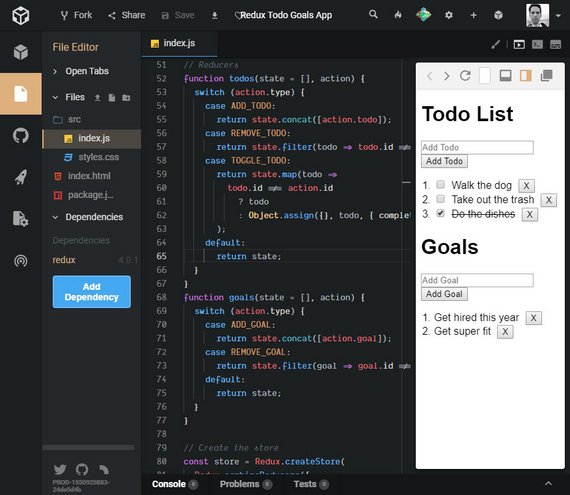

We then refactored our entire todos reducer to use a switch statement rather than multiple if/else statements:

function todos(state = [], action) {

switch (action.type) {

case 'ADD_TODO':

return state.concat([action.todo]);

case 'REMOVE_TODO':

return state.filter(todo => todo.id !== action.id);

case 'TOGGLE_TODO':

return state.map(todo =>

todo.id !== action.id

? todo

: Object.assign({}, todo, { complete: !todo.complete })

);

default:

return state;

}

}

In the above snippet, we matched cases against an expression (i.e., action.type), and executed statements associated with that particular case.

Let’s now extend our app with some additional functionality!

1.6.2 Adding Goals to our App

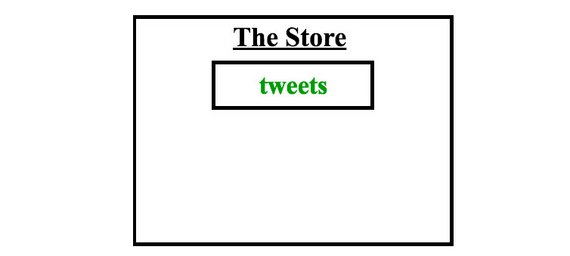

Currently, the app keeps track of a single piece of state - a list of todo items.

Let’s make the app a bit more complicated and add in a second piece of state for our app to track - goals.

We now are going to add a goals reducer to track goals as well.

function goals(state = [], action) {

switch (action.type) {

case 'ADD_GOAL':

return state.concat([action.todo]);

case 'REMOVE_GOAL':

return state.filter(goal => goal.id !== action.id);

default:

return state;

}

}

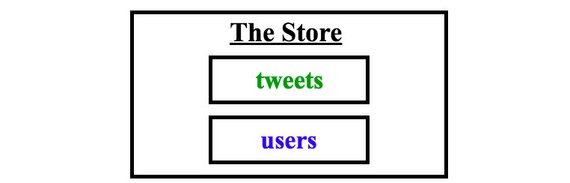

Now have two reducer functions:

- todos

- goals

However, the createStore() function we built can only handle a single reducer function:

// createStore takes one reducer function as an argument

const store = createStore(todos);

We can’t call createStore() passing it two reducer functions:

// this will not work

const store = createStore(todos, goals);

So we’ve got a problem…

1.6.3 Multiple Reducers

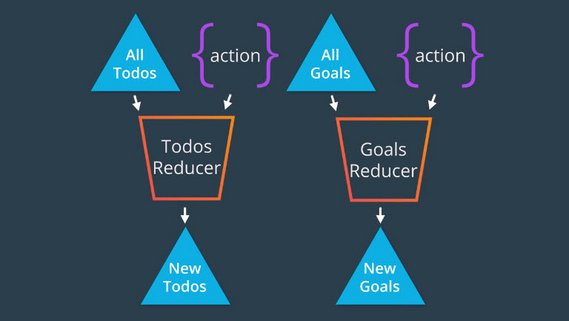

At this point, we now have two reducers, our Todos Reducer and our Goals Reducer. Each is responsible for handling their specific slice of the state tree.

This introduces a new problem though. When we called createStore we passed it our single Todos reducer.

const store = createStore(todos);

Whenever dispatch was called, we’d call this reducer, passing it the current state and the action which was dispatched, and we get back the new state.

Well, now we not only have our Todos reducer, we also have our Goals reducer and each are expected to receive their specific slice of the state tree whenever an action is dispatched.

What we need to do is instead of passing createStore our single Todos reducer, we want to create almost like a root reducer function, which will be responsible for calling the correct reducer whenever specific actions are dispatched.

What we need is our app to now work with both our to Todos reducer as well as our Goals reducer.

Let’s see what that will look like.

function todos(state = [], action) {

switch (action.type) {

case 'ADD_TODO':

return state.concat([action.todo]);

case 'REMOVE_TODO':

return state.filter(todo => todo.id !== action.id);

case 'TOGGLE_TODO':

return state.map(todo =>

todo.id !== action.id

? todo

: Object.assign({}, todo, { complete: !todo.complete })

);

default:

return state;

}

}

function goals(state = [], action) {

switch (action.type) {

case 'ADD_GOAL':

return state.concat([action.goal]);

case 'REMOVE_GOAL':

return state.filter(goal => goal.id !== action.id);

default:

return state;

}

}

function app(state = {}, action) {

return {

todos: todos(state.todos, action),

goals: goals(state.goals, action)

};

}

// Create the store passing the root reducer.

const store = createStore(app);

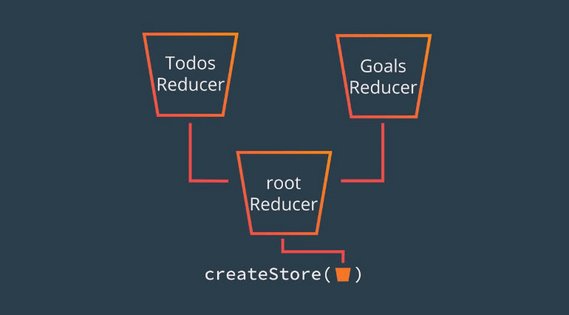

The app started out with one piece of state, todos, when we added in the goals state, we now had two separate pieces of state. Each piece of state needed its own reducer.

Since the create store function can only take in one reducer, we had to create a reducer that acts as the main reducer, commonly called the root reducer, that in turn calls both of the other reducers to get each piece of state to build the final state of the app.

1.6.4 Quiz Question

Select all statements that are true.

[x] Reducers must be pure [x] Though each reducer handles a different slice of state, we must combine reducers into a single reducer to pass to the store [x]

createStore()takes only onereducerargument [x] Reducers are typically named after the slices of state they manage.

1.6.5 Summary

In this section, we bolstered our application to handle a number of different actions as well as an entirely new piece of state! In addition to our app handling the ADD_TODO action, it now handles:

- the REMOVE_TODO action

- the TOGGLE_TODO action

We also created the goals reducer which handles:

- an ADD_GOAL action

- a REMOVE_GOAL action

So our application can now manage the state of our todos and goals, and it can do all of this, predictably!

In the next and final section of this lesson, we’ll look at how we can convert some of our existing functionality to follow best practices.

1.7 Better Practices

The next thing for us to do is implement constants in place of strings. This is a less error-prone way of programming.

// App code (reducer)

const ADD_TODO = 'ADD_TODO';

const REMOVE_TODO = 'REMOVE_TODO';

const TOGGLE_TODO = 'TOGGLE_TODO';

const ADD_GOAL = 'ADD_GOAL';

const REMOVE_GOAL = 'REMOVE_GOAL';

function todos(state = [], action) {

switch (action.type) {

case ADD_TODO:

return state.concat([action.todo]);

case REMOVE_TODO:

return state.filter(todo => todo.id !== action.id);

case TOGGLE_TODO:

return state.map(todo =>

todo.id !== action.id

? todo

: Object.assign({}, todo, { complete: !todo.complete })

);

default:

return state;

}

}

function goals(state = [], action) {

switch (action.type) {

case ADD_GOAL:

return state.concat([action.goal]);

case REMOVE_GOAL:

return state.filter(goal => goal.id !== action.id);

default:

return state;

}

}

1.7.1 Question 1 of 2

Why prefer constants over strings in action types?

- Constants are more serializable

- We can ensure an error will be thrown for misspelled action types

- There is no difference between using constants versus strings

1.7.2 Action Creators

Next we want to write code so we don’t have to repeat ourselves on each dispatch invocation.

Here are each of the dispatch calls. We can see that we are repeating ourselves quite a bit.

store.dispatch({

type: ADD_TODO,

todo: { id: 0, name: 'Wash the car', complete: false }

});

store.dispatch({

type: ADD_TODO,

todo: { id: 1, name: 'Walk the dog', complete: true }

});

store.dispatch({

type: ADD_TODO,

todo: { id: 2, name: 'Go to the gym', complete: true }

});

store.dispatch({

type: TOGGLE_TODO,

id: 0

});

store.dispatch({

type: REMOVE_TODO,

id: 0

});

store.dispatch({

type: ADD_GOAL,

goal: { id: 0, name: 'Learn Redux' }

});

store.dispatch({

type: ADD_GOAL,

goal: { id: 1, name: 'Learn Python' }

});

store.dispatch({

type: ADD_GOAL,

goal: { id: 2, name: 'Learn Vue' }

});

store.dispatch({

type: REMOVE_GOAL,

id: 0

});

What we are going to do is write Action Creators which will build the action that will be passed to our store on dispatch.

// Action creators

function addTodoAction(todo) {

return {

type: ADD_TODO,

todo

};

}

function removeTodoAction(id) {

return {

type: REMOVE_TODO,

id

};

}

function toggleTodoAction(id) {

return {

type: TOGGLE_TODO,

id

};

}

function addGoalAction(goal) {

return {

type: ADD_GOAL,

goal

};

}

function removeGoalAction(id) {

return {

type: REMOVE_GOAL,

id

};

}

Now we can have a much more concise dispatch invocation.

// dispatch an action

store.dispatch(addTodoAction({ id: 0, name: 'Wash the car', complete: false }));

store.dispatch(addTodoAction({ id: 1, name: 'Walk the dog', complete: true }));

store.dispatch(addTodoAction({ id: 2, name: 'Go to the gym', complete: true }));

store.dispatch(toggleTodoAction(0));

store.dispatch(removeTodoAction(0));

store.dispatch(addGoalAction({ id: 0, name: 'Learn Redux' }));

store.dispatch(addGoalAction({ id: 1, name: 'Learn Python' }));

store.dispatch(addGoalAction({ id: 2, name: 'Learn Vue' }));

store.dispatch(removeGoalAction(0));

1.7.3 Question 2 of 2

/* Create An Action Creator

*

* You need to create an action creator called 'mealCreator' that should:

* - Accept an id

* - Return a Redux action with a 'type' property that has a value

* of 'CREATE_MEAL'

* - Include the id passed to the action creator

*/

const CREATE_MEAL = 'CREATE_MEAL';

> function mealCreator(id) {

return {

type: CREATE_MEAL,

id

};

}

1.7.4 Summary

In this section, we converted our actions to use JavaScript constants instead of strings. We also refactored our .dispatch() calls from passing in unique objects directly to them, to calling special functions that create the action objects - these special functions that create action objects are called Action Creators.

1.8 Lesson Summary

We’ve now covered the most important parts of the state management library.

- The Store

- Internal state

- getting state

- listening for changes

- updating state

- Actions

- Reducers

2. UI + Redux

2.1 Introduction

In the previous lesson, we learned how to improve the predictability of the state in our application by building our own state management library.

In this lesson, we’ll take that state management library and add some UI to it. This will allow us to take a closer look at how our custom library can manage the state of an actual application.

2.2 UI

2.2.1 Move code to HTML

What we will do is host our javascript in html. We create index.html with the following code.

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html lang="en">

<head>

<meta charset="UTF-8">

<meta name="viewport" content="width=device-width, initial-scale=1.0">

<meta http-equiv="X-UA-Compatible" content="ie=edge">

<title>Udacity Todos Goals</title>

</head>

<body>

<script>

// copy store code into here

</script>

</body>

</html>

We now want make sure to copy our JavaScript into this html and delete index.js.

2.2.2 What We’re Going to Build

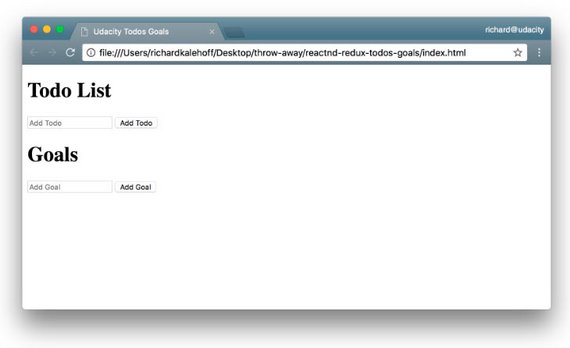

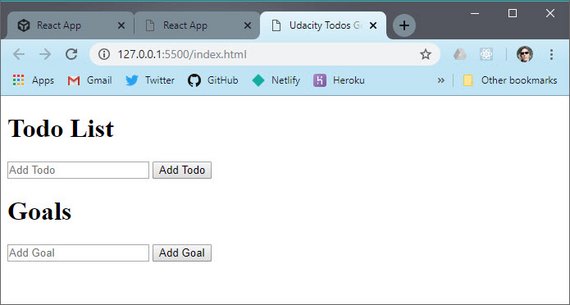

Now that we have an index.html file and all of the JavaScript code has been transferred over to script tags, let’s start adding in a User Interface. Since our project has two pieces of state, we’ll need two areas:

- Todo list area

- Goals area

So this is what we’re going for. It’s not the best looking website ever created, but this isn’t a course on CSS ;-). If you want to make it stunningly beautiful, feel free to add some CSS to your project 👍🏼

We already have the Redux portion of our application working, but so far, we’ve just been manually running snippets of code to interact with the Redux Store. Let’s create the UI above so that we can interact with the store using the browser.

2.2.3 Basic UI

So, now what the eventual goal here, is we want to show both our Todo list, as well as our goals list. We want to give the user an option to add new items to both lists via the UI right now.

So basically, our library code is going to manage the state of our application and the DOM or the view, is just going to be a representation of that state.

What we need to do is to add some actual UI to our app, so we could hook that UI up to our library code in order to get the state of our application.

<body>

<div>

<h1>Todo List</h1>

<form id="todoForm">

<input id='todo' type='text' placeholder='Add Todo' required />

<button id='todoBtn'>Add Todo</button>

</form>

<ol id='todos'></ol>

</div>

<div>

<h1>Goals</h1>

<form id="goalForm">

<input id='goal' type='text' placeholder='Add Goal' required />

<button id='goalBtn'>Add Goal</>

</form>

<ul id='goals'></ul>

</div>

<script>

// store code here

</script>

</body>

Here’s what the UI looks like right now.

GitHub Repo: reactnd-redux-todos-goals@11-build-ui

2.2.4 Summary

In this section, we added some minimal UI to our application. The actually state of our app hasn’t changed at all, though.

In the next section, we’ll hook up our shiny new UI to our state so that entering content via the UI will update the application’s state.

2.3 UI + State

The changes we’ll add will make is so whenever the Todo input field is submitted, it will add a Todo item to the state…and whenever the Goal input field is submitted, it will add a new Goal item to the state.

Let’s break this down into the steps that happen. First, we need to listen for when the buttons are clicked; we did this with the plain DOM .addEventListener() method:

document.getElementById('todoForm').addEventListener('submit', addTodo)

document.getElementById('goalForm').addEventListener('submit', addGoal)

Pressing the #todoBtn will call addTodo which will add the new item to the state:

function generateId() {

return (

Math.random()

.toString(36)

.substr(2) + new Date().getTime().toString(36)

);

}

// DOM code

function addTodo (e) {

e.preventDefault();

const input = document.getElementById('todo')

const name = input.value

input.value = ''

store.dispatch(

addTodoAction({

name,

complete: false,

id: generateId()

})

);

input.value = '';

}

function addGoal(e) {

e.preventDefault();

const input = document.getElementById('goal');

const name = input.value;

store.dispatch(

addGoalAction({

id: generateId(),

name

})

);

input.value = '';

}

This method will extract the information from the input field, reset the input field, and then dispatch an addTodoAction Action Creator with the text that the user typed into the input field.

So we’re using the UI to change the state of our store, but these changes are not reflecting the new state visually in the UI. Let’s do that, now.

Here are some of the DOM manipulations we’re using.

- accessing elements with document.getElementById()

- adding listeners with .addEventListener()

- accessing the .value property on an element

- creating a new element with .createElement()

- adding new content with.appendChild()

2.3.1 Display added item in UI

Next we add code to display to the DOM whenever an item is added.

function addTodoToDOM(todo) {

const node = document.createElement('li');

const text = document.createTextNode(todo.name);

node.appendChild(text);

document.getElementById('todos').appendChild(node);

}

function addGoalToDOM(goal) {

const node = document.createElement('li');

const text = document.createTextNode(goal.name);

node.appendChild(text);

document.getElementById('goals').appendChild(node);

}

We trigger these functions within our subscribe method of the store.

store.subscribe(() => {

// console.log('The new state is: ', store.getState());

const { todos, goals } = store.getState();

document.getElementById('goals').innerHTML = '';

document.getElementById('todos').innerHTML = '';

todos.forEach(addTodoToDOM); // todos.forEach(todo => addTodoToDOM(todo));

goals.forEach(addGoalToDOM); // goals.forEach(goal => addGoalToDOM(goal));

});

We add some styling to our UI.

<style>

body {

display: flex;

justify-content: space-around;

}

ul, ol {

padding: 0 0 0 20px;

}

input[type='checkbox'] {

margin-right: 10px;

}

</style>

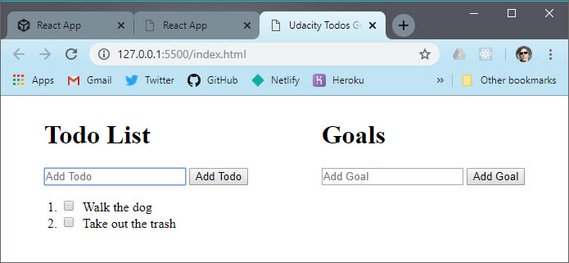

Here’s the updated UI.

GitHub Repo: reactnd-redux-todos-goals@12-dispatch-from-ui

2.3.2 Add Toggle item to UI

Next we update the UI with the ability to click a todo and mark it as complete.

function addTodoToDOM(todo) {

const li = document.createElement('li');

const checkbox = document.createElement('input');

checkbox.id = todo.id;

checkbox.setAttribute('type', 'checkbox');

checkbox.addEventListener('click', () => {

store.dispatch(toggleTodoAction(todo.id));

});

const label = document.createElement('label');

const text = document.createTextNode(todo.name);

label.htmlFor = todo.id;

label.appendChild(text);

li.appendChild(checkbox);

li.appendChild(label);

if (todo.complete) {

label.classList.add('strike');

checkbox.checked = true;

}

document.getElementById('todos').appendChild(li);

}

Here’s the style we added.

<style>

.strike {

text-decoration: line-through;

}

</style>

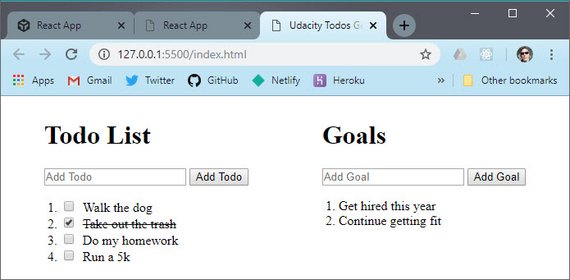

Now the updated UI looks like this.

GitHub Repo: reactnd-redux-todos-goals@13-dispatch-toggle

2.3.3 Add Remove items from UI

Lastly we add the remove functionality.

function createRemoveButton(onClick) {

const removeBtn = document.createElement('button');

removeBtn.classList.add('removeBtn');

removeBtn.innerHTML = 'X';

removeBtn.addEventListener('click', onClick);

return removeBtn;

}

function addTodoToDOM(todo) {

// todo item code

const removeBtn = createRemoveButton(() => {

store.dispatch(removeTodoAction(todo.id));

});

li.appendChild(removeBtn);

document.getElementById('todos').appendChild(li);

}

function addGoalToDOM(goal) {

// goal item code

const removeBtn = createRemoveButton(() => {

store.dispatch(removeGoalAction(goal.id));

});

node.appendChild(removeBtn);

document.getElementById('goals').appendChild(node);

}

The additional style looks like this.

<style>

.removeBtn {

margin-left: 10px;

}

</style>

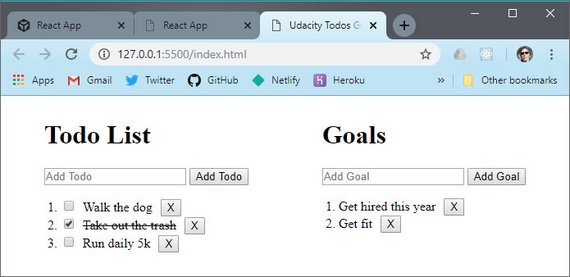

Here’s the updated UI.

GitHub Repo: reactnd-redux-todos-goals@14-dispatch-remove-items

2.3.4 Summary

In this section, we connected our functioning state application with a front-end UI. We added some form fields and buttons to our UI that can be used to add new Todo items and Goal items to the state. Updating the state will also cause the entire application to re-render so that the visual representation of the application matches that of the info stored in the state object.

Now, we wrote all of this code ourselves. In the next section, we’ll convert from using our custom library to using Redux.

2.4 Introducing Redux

Up until now we haven’t worked with Redux directly. What we did was create our own version of Redux that follows the Redux API exactly.

Just like the library we built ourselves, Redux has a state management library that has a store, actions, and reducers.

Let’s go ahead and replace our own implementation with the real Redux, so you can see just how similar they are.

2.4.1 Replacing Library code with Redux

We’re going to transition away from our custom code to using the actual Redux library.

We first link to the hosted version of the Redux library with the following line.

<script src="https://cdnjs.cloudflare.com/ajax/libs/redux/3.7.2/redux.min.js">

</script>

Then we remove the library code from index.html.

/* Removed...

// Library code

function createStore(reducer) {

// The store should have four parts

// 1. The state

// 2. Get the state

// 3. Listen for changes on the state

// 4. Update the state

let state;

let listeners = [];

const getState = () => state;

const subscribe = listener => {

listeners.push(listener);

return () => {

listeners = listeners.filter(l => l !== listener);

};

};

const dispatch = action => {

state = reducer(state, action);

listeners.forEach(listener => listener());

};

return {

getState,

subscribe,

dispatch

};

}

*/

Then we remove our root reducer and custom createStore function. Those are replaced with Redux.createStore and Redux.combineReducers methods.

/* Removed...

function app(state = {}, action) {

return {

todos: todos(state.todos, action),

goals: goals(state.goals, action)

};

}

// Create the store

const store = createStore(app);

*/

const store = Redux.createStore(

Redux.combineReducers({

todos,

goals

})

);

2.4.2 Reducer composition

Reducer composition sounds intimidating, but it’s simpler than you might think. The idea is that you can create a reducer to manage not only each section of your Redux store, but also any nested data as well.

Let’s say we were dealing with a state tree like had this structure.

{

users: {},

setting: {},

tweets: {

btyxlj: {

id: 'btyxlj',

text: 'What is a jQuery?',

author: {

name: 'Tyler McGinnis',

id: 'tylermcginnis',

avatar: 'twt.com/tm.png'

}

}

}

}

We have three main properties on our state tree: users, settings, and tweets. Naturally, we’d create individual reducers for each and then create a single root reducer using Redux’s combineReducers method.

const reducer = combineReducers({

users,

settings,

tweets

})

combineReducers, under the hood, is our first look at reducer composition.

combineReducers is responsible for invoking all the other reducers, passing them the portion of their state that they care about. We’re making one root reducer, by composing a bunch of other reducers together.

With that in mind, let’s take a closer look at our tweets reducer and how we can leverage reducer composition again to make it more compartmentalized. Specifically, let’s look how a user might change their avatar with the way our store is currently structured. Here’s the skeleton with what we’ll start out with.

function tweets (state = {}, action) {

switch(action.type){

case ADD_TWEET :

...

case REMOVE_TWEET :

...

case UPDATE_AVATAR :

???

}

}

What we’re interested in is that last one, UPDATE_AVATAR. This one is interesting because we have some nested data - and remember, reducers have to be pure and can’t mutate any state. Here’s one approach.

function tweets (state = {}, action) {

switch(action.type){

case ADD_TWEET :

...

case REMOVE_TWEET :

...

case UPDATE_AVATAR :

return {

...state,

[action.tweetId]: {

...state[action.tweetId],

author: {

...state[action.tweetId].author,

avatar: action.newAvatar

}

}

}

}

}

That’s a lot of spread operators. The reason for that is because, for every layer, we’re wanting to spread all the properties of that layer on the new objects we’re creating (because, immutability). What if, just like we separated our tweets, users, and settings reducers by passing them the slice of the state tree they care about, what if we do the same thing for our tweets reducer and its nested data. Doing that, the code above would be transformed to look like this

function author (state, action) {

switch (action.type) {

case : UPDATE_AVATAR

return {

...state,

avatar: action.newAvatar

}

default :

state

}

}

function tweet (state, action) {

switch (action.type) {

case ADD_TWEET :

...

case REMOVE_TWEET :

...

case : UPDATE_AVATAR

return {

...state,

author: author(state.author, action)

}

default :

state

}

}

function tweets (state = {}, action) {

switch(action.type){

case ADD_TWEET :

...

case REMOVE_TWEET :

...

case UPDATE_AVATAR :

return {

...state,

[action.tweetId]: tweet(state[action.tweetId], action)

}

default :

state

}

}

All we’ve done is separated out each layer of our nested tweets data into their own reducers. Then, just like we did with our root reducer, we’re passing those reducers the slice of the state they care about.

2.4.3 Quiz Question

What is wrong with the following root reducer?

import { combineReducers } from 'redux';

import booksReducer from './books_reducer';

import userReducer from './user_reducer';

const rootReducer = combineReducers(booksReducer, userReducer);

export default rootReducer;

- An object that maps state keys to reducers should be passed into

combineReducers()

The correct code should look like this.

import { combineReducers } from 'redux';

import booksReducer from './books_reducer';

import userReducer from './user_reducer';

const rootReducer = combineReducers({

books: booksReducer,

users: userReducer

});

export default rootReducer;

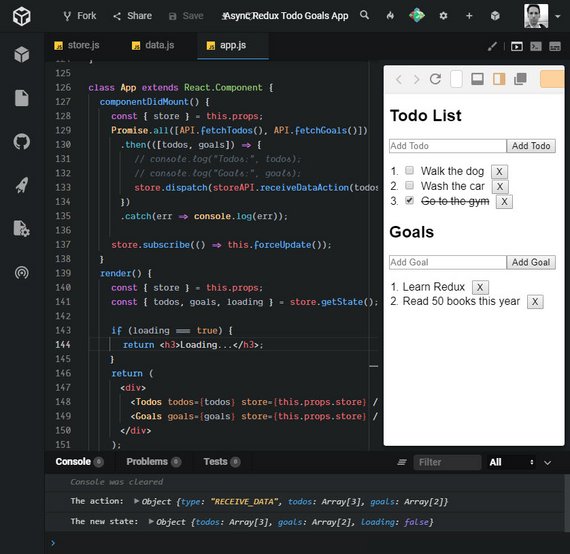

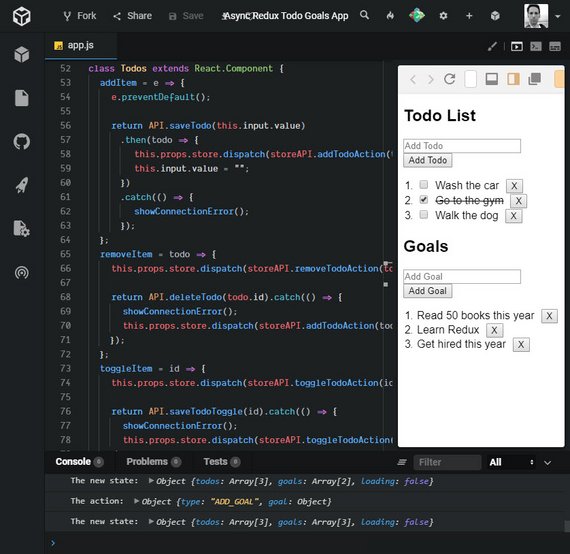

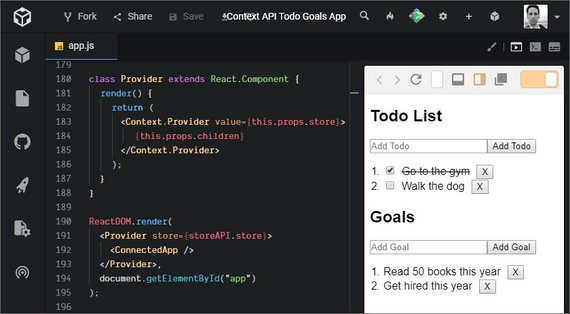

Here is a version of the app on CodeSandbox.

Live Demo: Redux Todo Goals App on CodeSandbox

2.4.4 Summary

In this section, we replaced the code we wrote in the previous lesson with the actual Redux library code. We saw that swapping out our code with Redux’s code didn’t change anything with how our application functions or how our app-specific code works. Redux is just a predictable state container.

What’s key to understand is that you’ve already learned 90% of Redux! Everything else from here on out will be handling specific use cases (combining Redux with a React application, how to work with asynchronous data modification, etc.).

We’ll be adding more concepts on top of what you know now, so if you feel comfortable with your understanding of Redux, then keep going. If you’re a bit hazy on how a specific part works, I definitely recommend you get the hazy bits nailed down now before proceeding on to more complicated content. Feel free to return to the first lesson to review specific Redux functionalities to iron out any confusing parts before moving on.

2.5 Articles & Questions

Read these articles:

2.5.1 Question 1 of 2

What are the advantages of using Redux?

- State is managed in one place

- Less error prone since components don’t track state separately

- State is kept out of the DOM

2.5.2 Question 2 of 2

Describe the 3 principles Redux follows.

- Single source of truth

- State for the whole application is stored in an object tree within a single store.

- State is read-only

- The only way to change the state is to emit an action - an object describing what happened.

- Changes are made with pure function

- To specify how the state tree is transformed by actions, you write pure reducers.

3. Redux Middleware

3.1 Introduction

The next thing we are going to do is intercept dispatch actions in order to filter out tasks that contain words which we don’t want to add.

For instance, my accountant has warned me NOT to buy Bitcoin. So, I want to filter that out prior to dispatching my actions.

What we can do is create a new function to do this.

// Middleware

function checkAndDispatch(store, action) {

if (

action.type === ADD_TODO &&

action.todo.name.toLowerCase().includes('bitcoin')

) {

return alert("Nope, that's a bad idea.");

}

if (

action.type === ADD_GOAL &&

action.goal.name.toLowerCase().includes('bitcoin')

) {

return alert("Nope, that's a bad idea.");

}

return store.dispatch(action);

}

What this does is show an alert if an attempt to add the word “bitcoin” is made. Otherwise the passed in action is dispatched.

What we also need to do is update all the store.dispatch calls with a call to checkAndDispatch.

function addTodo(e) {

e.preventDefault();

const input = document.getElementById('todo');

const name = input.value;

// store.dispatch(

// addTodoAction({

// name,

// complete: false,

// id: generateId()

// })

// );

checkAndDispatch(

store,

addTodoAction({

name,

complete: false,

id: generateId()

})

);

input.value = '';

}

We make this change to all instances of store.dispatch.

3.2 Redux Middleware

Normally, when we call store.dispatch this signals the reducer to run with the action we passed dispatch.

When we added a checkAndDispatch function this required us to manually insert a function ahead of each store.dispatch call.

Wouldn’t it be nice if we could insert code in-between store.dispatch and the reducer without having to change all the calls?

Well this what middleware does.

You’ve learned how Redux makes state management more predictable: in order to change the store’s state, an action describing that change must be dispatched to the reducer. In turn, the reducer produces the new state. This new state replaces the previous state in the store. So the next time store.getState() is called, the new, most up-to-date state is returned.

Between the dispatching of an action and the reducer running, we can introduce code called middleware to intercept the action before the reducer is invoked. The Redux docs describe middleware as:

a third-party extension point between dispatching an action, and the moment it reaches the reducer.

What’s great about middleware is that once it receives the action, it can carry out a number of operations, including:

- producing a side effect (e.g., logging information about the store)

- processing the action itself (e.g., making an asynchronous HTTP request)

- redirecting the action (e.g., to another piece of middleware)

- dispatching supplementary actions

or even some combination of the above! Middleware can do any of these before passing the action along to the reducer.

Here’s what we do to add in real Redux middleware.

Create a function with this pattern. This is a currying pattern that for better or worse is what was adopted when this was built.

It passes a function to a function. Here’s the ES5 pattern which we will update below.

// Middleware

function checker(store) {

return function(next) {

return function(action) {

// do work

};

};

}

Now we move our code from checkAndDispatch and delete checkAndDispatch.

// Middleware

function checker(store) {

return function(next) {

return function(action) {

// do work

if (

action.type === ADD_TODO &&

action.todo.name.toLowerCase().includes('bitcoin')

) {

return alert("Nope, that's a bad idea.");

}

if (

action.type === ADD_GOAL &&

action.goal.name.toLowerCase().includes('bitcoin')

) {

return alert("Nope, that's a bad idea.");

}

return next(action);

};

};

}

Next we make a modification to our createStore method to add in the middleware component as the second argument to createStore.

const store = Redux.createStore(

Redux.combineReducers({

todos,

goals

}),

Redux.applyMiddleware(checker)

);

The last change has to do with the currying middleware function. This will be updated to use ES6. Here is the pattern.

const checker = store => next => action => {

}

The full function looks like this.

const checker = store => next => action => {

if (

action.type === ADD_TODO &&

action.todo.name.toLowerCase().includes('bitcoin')

) {

return alert("Nope, that's a bad idea.");

}

if (

action.type === ADD_GOAL &&

action.goal.name.toLowerCase().includes('bitcoin')

) {

return alert("Nope, that's a bad idea.");

}

return next(action);

}

3.2.1 Middleware Code Explained

The way we had to structure our code originally, our checkAndDispatch() function had to run before store.dispatch(). Why is this? Because when store.dispatch() is invoked, it immediately calls the reducer that was passed in when createStore() was invoked.

If you remember back to the first lesson, this is what our dispatch() function looked like (and is very similar to the real Redux dispatch() function):

const dispatch = (action) => {

state = reducer(state, action)

listeners.forEach((listener) => listener())

}

So you can see that calling store.dispatch() will immediately invoke the reducer() function. There’s no way to run anything in between the two function calls. So that’s why we had to make our checkAndDispatch() so that we can run verification code before calling store.dispatch().

However, this isn’t maintainable. If we wanted to add another check, then we’d need to write another preceding function, that then calls checkAndDispatch() that then calls store.dispatch(). Not maintainable at all.

With Redux’s middleware feature, we can run code between the call to store.dispatch() and reducer(). The reason this works, is because Redux’s version of dispatch() is a bit more sophisticated than ours was, and because we provide the middleware functions when we create the store.

const store = Redux.createStore( <reducer-function>, <middleware-functions> )

Redux’s createStore() method takes the reducer function as its first argument, but then it can take a second argument of the middleware functions to run. Because we set up the Redux store with knowledge of the middleware function, it runs the middleware function between store.dispatch() and the invocation of the reducer.

3.2.2 Applying Middleware

Just as we saw, we can implement middleware into a Redux app by passing it in when creating the store. More specifically, we can pass in the applyMiddleware() function as an optional argument into createStore(). Here’s the applyMiddleware() signature:

applyMiddleware(...middlewares)

Note the spread operator on the middlewares parameter. This means that we can pass in as many different middleware as we want! Middleware is called in the order in which they were provided to applyMiddleware().

We currently have the checker middleware applied to our app, but we’ll soon add a new logger middleware as well. To create a Redux store that uses our checker middleware, we can do the following:

const store = Redux.createStore(rootReducer, Redux.applyMiddleware(checker))

💡Functions Returning Functions 💡

Redux middleware leverages a concept called higher-order functions. A higher-order function is a function that either:

- accepts a function as an argument

- returns a function

Higher-order functions are a powerful programming technique that allow functions to be significantly more dynamic. You’ve actually already written a higher-order function in this course.

The

createRemoveButton()function is a higher-order function because theonClickparameter is expected to be a function (becauseonClickis set up as an event listener callback function.function createRemoveButton(onClick) { // <- here const removeBtn = document.createElement('button'); removeBtn.classList.add('removeBtn'); removeBtn.innerHTML = 'X'; removeBtn.addEventListener('click', onClick); // <- here return removeBtn; } const removeBtn = createRemoveButton(() => { store.dispatch(removeTodoAction(todo.id)); }); li.appendChild(removeBtn); const removeBtn = createRemoveButton(() => { store.dispatch(removeGoalAction(goal.id)); }); node.appendChild(removeBtn);For a refresher on higher-order functions, feel free to check out Lesson 2 in Object-Oriented JavaScript.

3.2.3 Question 1 of 2

Which of the following are true statements about middleware? Select all that apply.

- Middleware intercepts a dispatched action before it reaches the reducer.

- The concept of “middleware” is exclusive to Redux apps.

- Using middleware lets you create a Redux store without a reducer.

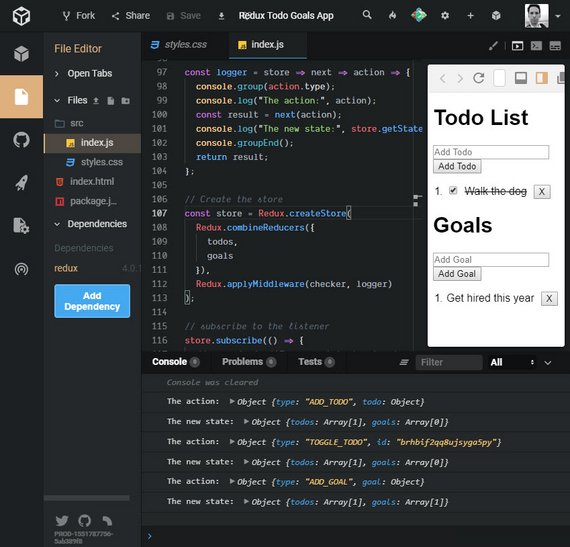

3.2.4 A New Middleware: Logging

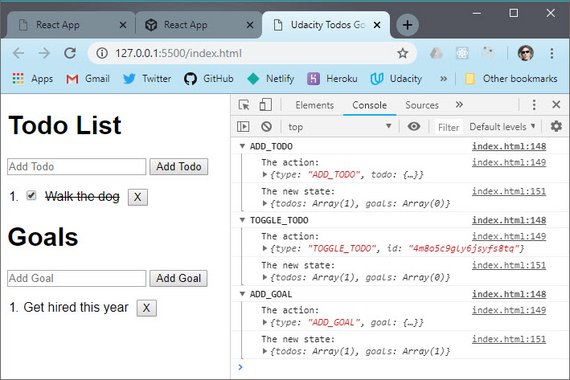

Currently, our application is making use of a single middleware: checker. Because we can use multiple middleware functions in a single application, let’s create a new middleware function called logger that will log out information about the state and action.

The benefits of this logger() middleware function are huge while developing the application. We’ll use this middleware to intercept all dispatch calls and log out what the action is that’s being dispatched and what the state changes to after the reducer has run.

Being able to see this kind of information will be immensely helpful while we’re developing our app. We can use this info to help us know what’s going on in our app and to help us track down any pesky bugs that creep in.

Here’s the logger middleware code addition.

const logger = store => next => action => {

console.group(action.type);

console.log('The action:', action);

const result = next(action);

console.log('The new state:', store.getState());

console.groupEnd();

return result;

};

Then we add it to our createStore invocation.

// Create the store

const store = Redux.createStore(

Redux.combineReducers({

todos,

goals

}),

Redux.applyMiddleware(checker, logger)

);

This creates a log entry whenever a dispatch action takes place.

Here’s the app on CodeSandbox

Live Demo: Redux Todo Goals App on CodeSandbox

3.2.5 Question 2 of 2

Which of the following are true statements about middleware? Select all that apply.

- Redux apps can only apply one type of middleware to the store.

Redux.applyMiddleware()can accept multiple arguments.- Middleware is optional.

- Middleware can be considered a third-party extension point between dispatching and having the action reach the reducer.

3.2.6 Lesson Challenge

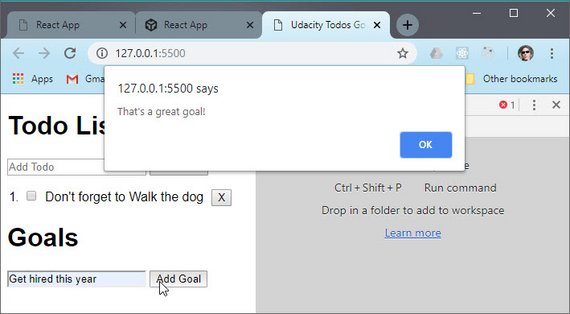

Write middleware to achieve the following behavior:

- Display an alert “That’s a great goal!” whenever a new goal is added.

- Display “Don’t forget to [name of your todo item]!” whenever a new todo item is added.

Make sure that the rest of the application works as intended (you see a list of your newly added goals and todo items).

The middleware looks like this.

const goalAffirmation = store => next => action => {

if (action.type === ADD_GOAL) {

alert("That's a great goal!");

}

return next(action);

};

const reminder = state => next => action => {

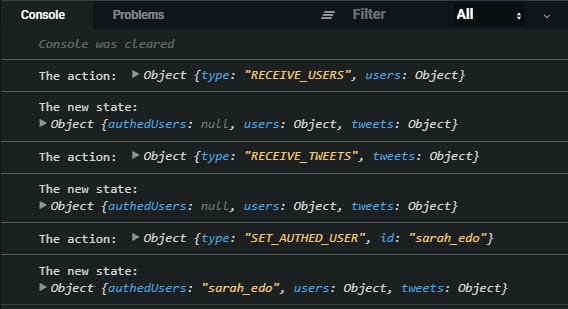

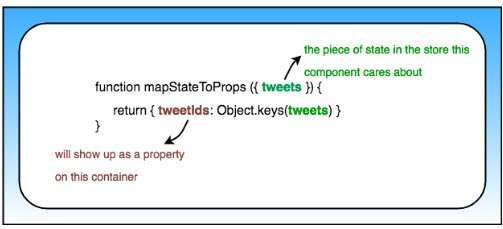

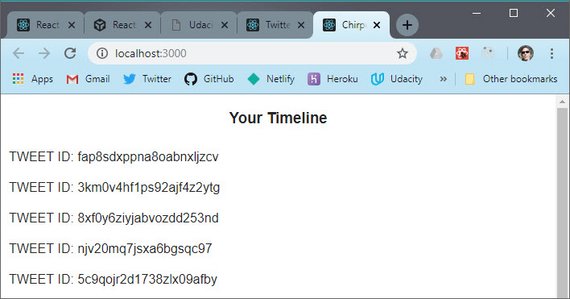

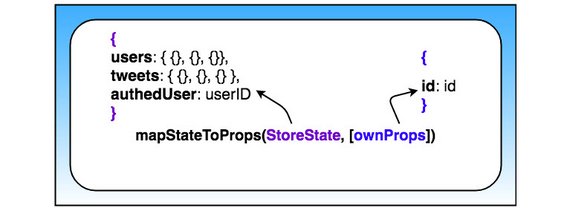

if (action.type === ADD_TODO) {