Chapter 15 - Web Storage

Notes from Programming in HTML5 with JavaScript & CSS3 Training Guide by Glenn Johnson.

This is part of my study material for passing Microsoft’s Exam 70-480: Programming in HTML5 with JavaScript & CSS3 certification exam.

Before Web Storage, the primary means of data storage was to send information back to the server, which requires the application to wait for a round-trip to occur.

To minimize the cost of relying entirely on server-side persistence, browsers now support web storage, a relatively new feature that enables storing small amounts of user data on the client machine.

This chapter begins with an overview of the two storage mechanisms (localStorage and sessionStorage) and how they can make dramatic improvements in how user data is retained. The chapter then examines how the use of storage events can combat complex problems such as race conditions and synchronization when the user has multiple tabs or browser instances open.

Lesson 1

1. Introducing web storage

Most web applications rely on some method of data storage, which usually involves a server-side solution such as a SQL Server database. However, in many scenarios, that might be excessive, and the ability to store simple, non-sensitive data in your browser would easily meet your needs.

After this lesson, you’ll be able to

- Understand web storage.

- Implement the

localStorageobject

2. Understanding cookies

For years, storing data in the browser could be accomplished by using HTTP cookies, which have provided a convenient way to store small bits of information. Today, cookies are used mostly for storing basic user profile information. The following is an example of how cookies are used.

function setCookie(cookieName, cookieValue, expirationDays) {

var expirationDate = new Date();

expirationDate.setDate(expirationDate.getDate() + expirationDays);

cookieValue = cookieValue + '; expires=' + expirationDate.toUTCString();

document.cookie = cookieName + '=' + cookieValue;

}

function getCookie(cookieName) {

var cookies = document.cookie.split(';');

for (let cookie of cookies) {

let index = cookie.indexOf('=');

let key = cookie.substr(0, index);

let val = cookie.substr(index + 1);

if (key.trim() === cookieName) { return val; }

}

}

window.onload = function() {

setCookie('firstName', 'James', 1);

var firstName = getCookie('firstName');

var div = document.getElementById('output');

div.innerHTML = firstName; // James

};

Live sample: ch15-WebStorage/a-cookie-original.html

3. Structuring code with Namespace patterns

While the code above illustrates how to set and retrieve cookie values, it’s not the best example of how to properly structure your code.

That said, this is a good place to show some additional ways of structuring code using four of Addy Osmani’s Essential JavaScript Namespacing Patterns.

The namespace patterns we’ll cover are:

- Single global variable

- Object literal notation

- Nested namespace pattern

- Immediately Invoked Function Expression (IIFE)

Namespace patterns

- Functions in global namespace - This is the code from above. It pollutes the global namespace and is prone to code collision. It is not one of the four examples but is included here for comparison.

// pattern var someValue = ''; var anotherValue = ''; thisFunction(/*...*/) { /*...*/ } thatFunction(/*...*/) { /*...*/ }function setCookie(/*...*/) { /*...*/ } function getCookie(/*...*/) { /*...*/ } setCookie('firstName', 'James', 1); var firstName = getCookie('firstName');Live sample: ch15-WebStorage/a-cookie-original.html

- Single global variable - This uses a single global variable and assigns to it an Immediately Invoked Function Expression (IIFE).

// pattern var myApplication = (function() { var myProp = ''; var myFunc = function() { /*...*/ }; return{ prop1: myProp, func1: myFunc } })();var cookieApp = (function() { var _setCookie = function(/*...*/) { /*...*/ }; var _getCookie = function(/*...*/) { /*...*/ }; return { getCookie: _getCookie, setCookie: _setCookie }; })(); cookieApp.setCookie('firstName1', 'James 1!', 1); var firstName = cookieApp.getCookie('firstName1');Live sample: ch15-WebStorage/a-cookie1-global-var.html

- Object literal notation - This can be thought of as an object containing a collection of key/value pairs. Object literals have the advantage of not polluting the global namespace and helping organize code and parameters logically.

// pattern var myApplication = { getInfo: function(){ /*...*/ }, /* we can also populate our object literal to support * further object literal namespaces */ models : {}, views : { pages : {} }, collections : {} };var cookieApp = cookieApp || {}; cookieApp = { setCookie: function(/*...*/) { /*...*/ }, getCookie: function(/*...*/) { /*...*/ } }; cookieApp.setCookie('firstName2', 'James 2!', 1); var firstName = cookieApp.getCookie('firstName2');Live sample: ch15-WebStorage/a-cookie2-literal-notation.html

- Nested namespace pattern - An extension of the object literal pattern is nested namespacing. It allows further segmentation and organization of code beyond a single level.

// pattern var myApp = myApp || {}; /* perform a similar existence check when defining nested children */ myApp.routers = myApp.routers || {}; myApp.model = myApp.model || {}; myApp.model.special = myApp.model.special || {};var myApp = myApp || {}; myApp.cookie = myApp.cookie || {}; myApp.cookie= { setCookie: function(/*...*/) { /*...*/ }, getCookie: function(/*...*/) { /*...*/ } }; myApp.cookie.setCookie('firstName3', 'James 3!', 1); var firstName = myApp.cookie.getCookie('firstName3');Live sample: ch15-WebStorage/a-cookie3-nested-namespace.html

- Immediately Invoked Function Expression - An IIFE is effectively an unnamed function which is immediately invoked after it’s been defined.

// pattern var namespace = namespace || {}; /* here a namespace object is passed as a function parameter. * this allows us to assign public methods and properties to it. */ (function( o ){ o.foo = "foo"; o.bar = function(){ return "bar"; }; })(namespace);var cookieApp = cookieApp || {}; (function(o) { o.setCookie = function(/*...*/) { /*...*/ }; o.getCookie = function(/*...*/) { /*...*/ }; })(cookieApp); cookieApp.setCookie('firstName4', 'James 4!', 1); var firstNAme = cookieApp.getCookie('firstName4');Live sample: ch15-WebStorage/a-cookie4-iife-wrapped.html

Code samples in upcoming lessons will be written to the global namespace. This is done to keep things simple and not convolute the concepts with an extra layer of code.

Keep in mind though, the patterns discussed above should be used at all times to best organize, encapsulate, and protect your code from collision.

One additional point is that these patterns specifically relate to namespacing and are separate and distinct from the object-oriented design patterns that were covered last week. This includes such things as constructor functions, inheritance patterns, and object reflection code.

The last thing to keep in mind is that both namespacing and object-oriented patterns can be combined to provide protection, encapsulation, and organization of your code.

4. Using the jQuery cookie plug-in

The example demonstrates that working with cookies isn’t complicated, but the interface for doing so leaves much to be desired. To simplify working with cookies, you can use the jQuery Cookie plug-in available at https://github.com/carhartl/jquery-cookie. Here is the modified code example when using the jQuery plug-in.

$.cookie('firstName', 'James');

var firstName = $.cookie('firstName');

This example shows that the plug-in provides a much simpler interface.

5. Working with cookie limitations

Cookies will continue to be an effective tool for the foreseeable future, but they have some drawbacks.

- Capacity limitations Cookies are limited to about 4KB of data, which is not large, although you can create more than 30 cookies per site. (The actual maximum limit depends on the browser being used; the average is between 30 and 50.)

- Overhead Every cookie is sent with each HTTP request/response made, regardless of whether the values are needed. This is often true even for requests for static content (such as images, css files, and js files), which can create heavier-than-necessary HTTP messages.

6. Understanding HTML5 storage

Older solutions such as plug-ins, flash player, or java applets left a lot to be desired; HTML5 broke new ground with several innovative tools. Each is unique and carries its own set of pros and cons.

- Web Storage Easily the simplest new form of storage, web storage provides a way to store key/value pairs of data in a manner that rivals cookies in ease of use. It is currently the most widely supported option and consists of both

localStorageandsessionStorage. - IndexedDB This option is a non-relational (NoSQL) database. It provides a simplicity that is similar to web storage while still accommodating common needs such as indexing and transactions. It has emerged as the clear winner with 95% browser coverage. It is promoted extensively by Google as part of their Progressive Web App (PWA) initiative and is used in tandem with Service Workers to provide a sophisticated offline first user experience.

- Web SQL

(deprecated)For more complex applications, this was a good alternative to web storage. It provided the power of a full relational database, including support for SQL commands, transactions, and performance tuning. It’s currently only supported by Chrome and Safari and does not work in IE, Firefox, or Edge. - Filesystem API

(deprecated)This tool was useful for storing larger data types such as text files, images, and movies. However, it suffers from a lack of adoption. It is currently only supported by Chrome.

7. Security considerations

Although the four storage types have many differences, they also have some striking similarities beyond all being vehicles for storing data on the client’s machine.

One property they all have in common is that the data being stored is tied to the URL (or, more specifically, the origin), which ensures that data can’t be accessed by other sites. Therefore, the same host, port, and protocol must be provided before a webpage can access data written by another page.

So, consider the following if data storage was created using this URL: http://www.example.com/area1/page1.html.

- http://www.otherexample.com/area1/page1.html - No, different domain

- http://store.example.com/area1/page1.html - No, different host

- http://example.com/area1/page1.html - No, different host

- https://www.example.com/area1/page1.html - No, different protocol

- http://www.example.com:8080/area1/page1.html - No, different ports

- http://www.example.com/area1/page2.html - Yes

- http://www.example.com/area2/page1.html - Yes

The strict association to the origin is an important consideration when developing sites that may be hosted on a shared domain. Keep in mind that if you are hosting on a shared domain, any of the sub-sites within the domain would also be able to access your data.

8. Browser support

Many HTML5 features have different levels of implementation and compatibility by the different browser manufacturers. This is especially true when working with different storage options. Coverage refers to the percentage of browsers in use worldwide that support this feature as of April 1, 2018, according to statistics provided by https://caniuse.com.

- Web Storage

- Supported - IE, Edge, Firefox, Chrome, Safari, iOS Safari, Chrome for Android, UC Browser Android, Samsung

- Not supported - Opera Mini

- Coverage - 96%

- IndexedDB

- Supported - IE, Edge, Firefox, Chrome, Safari, iOS Safari, Chrome for Android, UC Browser Android, Samsung

- Not supported - Opera Mini

- Coverage - 95%

- Web SQL

(deprecated) support may be dropped- Supported - Chrome, Safari, iOS Safari, Chrome for Android, UC Browser Android, Samsung

- Not supported - IE, Edge, Firefox, Opera Mini

- Coverage - 85%

- FileSystem API

(deprecated) support may be dropped- Supported - Chrome, Chrome for Android, Samsung

- Not Supported - IE, Edge, Firefox, Safari, iOS Safari, Opera Mini, UC Browser Android

- Coverage - 62%

This chapter examines two types of web storage: localStorage and sessionStorage.

9. Exploring localStorage

The localStorage global variable is a Storage object. One of the greatest strengths of localStorage is its simple API for reading and writing key/value pairs of strings. Because it’s essentially a NoSQL store, it’s easy to use by nature.

9a. localStorage object reference

The following is a list of methods and attributes available on the Storage object as it pertains to localStorage.

-

setItem(key, value) Method that stores a value by using the associated key. The following is an example of how you can store the value of a text box in

localStorage. The syntax for setting a value is the same for a new key as for overwriting an existing value.localStorage.setItem('firstName', $('#firstName').val()); // Since it's treated like many other JavaScript dictionaries, // you could also set values using other common syntaxes. localStorage['firstName'] = $('#firstName').val(); // or localStorage.firstName = $('#firstName').val(); -

getItem(key) Method of retrieving a value by using the associated key. The following example retrieves the value for the

firstNamekey. If an entry with the specified key does not exist,nullwill be returned.var firstName = localStorage.getItem('firstName'); // And like setItem, you also have the ability to use other // syntaxes to retrieve values from the dictionary var firstName = localStorage['firstName']; // or var firstName = localStorage.firstName; -

removeItem(key) Method to remove a value from

localStorageby using the associated key. The following example removes the entry with the given key. However, it does nothing if the key is not present in the collection.localStorage.removeItem('firstName'); -

clear() Method to remove all items from storage. If no entries are present, it does nothing. The following is an example of clearing the

localStorageobject.localStorage.clear(); -

length Property that gets the number of entries currently being stored. The following example demonstrates the use of the length property.

var itemcount = localStorage.length; -

key(index) Method that finds a key at a given index. The World Wide Web Consortium (W3C) indicates that if an attempt is made to access a key by using an index that is out of the range of the collection,

nullshould be returned. However, some browsers will throw an exception if an out-of-range index is used, so it’s recommended to check the length before indexing keys.var key = localStorage.key(1);

9b. High browser support

Another benefit of localStorage, as seen in the previous section, is that localStorage, in addition to sessionStorage, and IndexedDB is well supported in all browsers. This is the case for both desktop and mobile browsers across various platforms.

9c. Feature detection

Although most browsers support web storage, it’s still a good idea to verify that it’s available in case the user is running an older browser version. If it’s not available, you could experience a null reference exception the first time an attempt is made to access localStorage or sessionStorage. There are several ways to check availability; the following is one example.

function isWebStorageSupported() {

return 'localStorage' in window;

}

if

(isWebStorageSupported()) {

localStorage.setItem('firstName', $('#firstName').val());

}

The popular JavaScript library Modernizr comes with a method that could do this check for you.

if (Modernizr.localstorage) {

localStorage.setItem('firstName', $('#firstName').val());

}

9d. Amount of data that can be kept in web storage

The localStorage object provides much more space than was unavailable with older tools. Modern browsers support a minimum of 5 MB of data, which is substantially more than is allowed through cookies (which is 4KB each).

9e. Reaching the storage limit

If the storage limit is reached, or if the user manually turns off storage capabilities, a QuotaExceededError exception is thrown. The following is an example of how you can use a try/catch block to keep your application from failing if that happens.

try {

localStorage.setItem('firstName', $('#firstName').val());

}

catch(e) {

// degrade gracefully

}

9f. Storing complex objects

Currently, only string values can be stored in web storage, but sometimes you might need to store more interesting items such as arrays or JavaScript object. To accomplish this, you can take advantage of some of the available JSON utility methods.

The following example creates a JSON object and uses the stringify() method to convert the value to a string that can then be placed in web storage.

var person = { firstName: 'James', lastName: 'Priest' };

localStorage.setItem('james', JSON.stringify(person));

You can then use the parse() method to deserialize a new instance of the object from the string representation that was stored in the previous example.

var person = JSON.parse(localStorage.getItem('glenn'));

Don’t forget that a potential drawback to cookies is that they are always included in web requests and responses, even if you don’t use them. The situation when using web storage is the opposite; its values are never automatically passed to the server. You can do this yourself by including vales in an AJAX call or by using JavaScript to copy the values into posted form elements.

10. Using short-term persistence with sessionStorage

In the previous section, you learned how to use localStorage, which , like cookies, is designed to retain data across multiple sessions. However, if you want topurge stored information, you must use the removeItem() or clear() method.

In addition to localStorage, you can use sessionStorage; it is also a Storage object, so the same methods and properties exist. The difference is that sessionStorage retains data for a single session only. After the user closes the browser window, records stored are automatically cleared. This is an important advantage because only a limited amount of space is available.

At their core, both localStorage and sessionStorage are firmly dedicated to their respective browser context. Because that context for localStorage includes other tabs and windows within the same URL base, its data is shared among all open instances.

In contrast, sessionStorage has a context that, by design, is extremely confined. It’s limited to a single browser tab or window. Its data cannot be passed from one tab to the next. However, the data can be shared among any <iframe> elements that exist on the page.

Quick check

- What object type are

localStorageandsessionStorage?Answer

- They are Storage objects.

11. Anticipating potential performance pitfalls

Web storage doesn’t come without a few drawbacks. This section covers some of the pitfalls of using localStorage and sessionStorage.

11a. Synchronous read & write to the hard drive

One of the biggest issues with the Storage object is that it operates synchronously, which can block the page from rendering while read/writes occur. The synchronous read/writes are even more costly because they are committed directly to the client’s hard drive. By itself, that might not be a cause for concern, but the following activities can make these interactions annoyingly slow for the user.

- Indexing services on the client machine

- Scanning for viruses

- Writing larger amounts of data

Although the amount of time it usually takes to perform these actions is typically too small to notice, they could lock the browser from rendering while it’s reading and writing values to the hard disk. With that in mind, it’s a good idea to use web storage for very small amounts of data and use alternative methods for larger items.

NOTE Why not use Web Workers to read/write asynchronously?

Web storage is not available within web workers. If you need to write a value while in web workers, you must use the

postMessage()method to notify the parent thread and allow it to perform the work instead.

11b. Anticipating slow search capabilities

Because web storage does not have indexing features, searching large data sets can be time consuming. This usually involves iterating over each item in the list to find items that match the search criteria.

11c. No transaction support

Another benefit of storage options that is missing from web storage is support for transactions. Although difficulties are unlikely in the majority of applications, applications using web storage can run into problems if a user is modifying the same value in localStorage within multiple open browser tabs. The result would be a race condition in which the second tab immediately overwrites the value inserted by the first tab.

Quick Check

- You would like to store the user’s name after he authenticates on your site, but he will need to authenticate again on his next visit, at which time you would reload his information (including name). Which storage mechanism should you use?

Answer

sessionStorage. Although you could uselocalStorageto store the user’s name, it would be held permanently. Placing it insessionStoragewould purge it automatically after the window is closed.

12. Google’s storage recommendations

Google makes some clear storage recommendations in these two articles:

While these articles specifically target offline and progressive web apps (PWAs), the recommendations hold true for online caching and storage needs as well.

Here are the highlights of these two articles…

12a. Storage comparisons

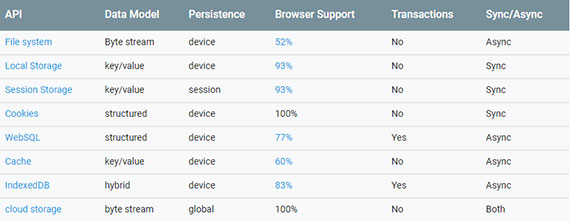

The two data points you should pay attention to in this chart are the Async APIs (which prevent blocking of the main thread) and highest browser support percentage.

The chart can be used to choose APIs that are most widely supported across many browsers and which offer asynchronous call models. This will help maximize interoperability with the UI by not blocking UI interactions.

These criteria lead naturally to the following technology choices:

| Need | Solution | Why |

|---|---|---|

| App state | IndexedDB | App state & user-generated content should use IndexedDB. This enables users to work offline in more browsers than just those that support the Cache API. |

| Offline Storage | Cache API | This API is available in any browser that supports Service Workers (The technology necessary for creating offline apps.) The Cache API is ideal for storing resources associated with a known URL. |

| Global byte data | Cloud Storage | Provides global persistence and is good for file systems and other hierarchically organized blobs of data. |

12b. The bottom line

Let’s get right to the point with a general recommendation for storing data offline:

- For the network resources necessary to load your app while offline, use the Cache API (part of service workers).

- For all other data, use IndexedDB (with a promises wrapper).

Here’s the rationale:

Both APIs are asynchronous (IndexedDB is event based and the Cache API is Promise based). They also work with web workers, window, and service workers.

IndexedDB is available everywhere. Service Workers (and the Cache API) are now available in Chrome, Firefox, Opera and are in development for Edge.

Promise wrappers for IndexedDB hide some of the powerful but also complex machinery (e.g. transactions, schema versioning) that comes with the IndexedDB library. IndexedDB will support observers, which allow easy synchronization between tabs.

For PWAs, you can cache static resources, composing your application shell (JS/CSS/HTML files) using the Cache API and fill in the offline page data from IndexedDB. Debugging support for IndexedDB is now available in Chrome (Application tab), Opera, Firefox (Storage Inspector) and Safari (see the Storage tab).

12c. Limitations of other storage mechanisms

- Web Storage (e.g LocalStorage and SessionStorage) is synchronous, has no Web Worker support and is size and type (strings only) limited

- Cookies have their uses but are synchronous, lack web worker support and are also size-limited.

- Web SQL does not have broad browser support and its use is not recommended.

- The File System API is not supported on any browser besides Chrome.

- The File API is being improved in the File and Directory Entries API and File API specs but neither is sufficiently mature or standardized to encourage widespread adoption yet.

13. Lesson summary

- Web storage provides you with an easy method for storing key/value pairs of data without relying on a server.

- With nearly universal support across current desktop and mobil browsers, web storage is the most supported form of offline data storage.

- Web storage comes in two forms, which have the same methods.

- localStorage Shares data across all windows and tabs within the same origin.

- sessionStorage Data is sandboxed to only the current tab or window and is cleared when closed.

- Reads/writes to web storage can be performed only synchronously

- Only storage for string values is currently supported within web storage, but storage for more complex objects can be achieved by using the

JSON.stringify()andJSON.parse()utility methods.

14. Lesson review

- Which of the following URLs can access data stored on http://www.example.com/lesson1/page1.html?

- http://www2.example.com/lesson1/page1.html

- http://www.example.com:8081/lesson1/page1.html

- https://www.example.com/lesson1/page1.html

- http://www.example.com/lesson2/page1.html

- http://example.com/lesson1/page1.html

- What is the web storage currently recommended by the W3C?

- 4 KB

- 5 MB

- 500 MB

- 10 MB

- What is the correct syntax for removing all values existing in

localStorage()?localStorage.clear();localStorage.removeAll();localStorage.abandon();localStorage.reset()

- Which of the following storage mechanisms has the highest level of crsos-browser support?

- Web storage

- Web SQL

- IndexedDB

- FileSystem API

- Which of the following features does web storage support?

- Indexing

- Transactions

- Asynchronous read/write

- Simple key/value pair storage

Lesson 2

15. Handling storage events

One of the biggest challenges you’ll face when working with web storage is keeping everything in sync when a user has multiple tabs or browser instances open at the same time.

For example, browser tab one might have displayed a value it retrieved from localStorage just before that entry was updated in browser tab two. In this scenario, tab one doesn’t know the value it displayed has just become stale.

To solve this problem, web storage has a storage event that is raised whenever an entry is added, updated, or removed. You can subscribe to this event within you application to provide notification when something has changed and inform you of specific details about those changes. These events work in both localStorage and sessionStorage.

After this lesson, you’ll be able to

- Understand the StorageEvent object.

- Implement event handling on the

localStorageobject.

16. Sending notifications only to other windows

The W3C recommends that events not be received in the tab (or window) that made the change when working with storage events. This makes sense because the intent is to allow other windows to respond when a storage value changes.

However, some browsers (such as earlier versions of Internet Explorer) have implemented storage events in a way that allows the source window to receive the notification, too. It is only safe to rely on this implementation if your application will target those browsers specifically.

17. StorageEvent object reference

Subscribers to the storage event receive a StorageEvent object containing detailed information about what has changed. The following is a list of properties included on the StorageEvent object.

- key Gets the key of the record that was added, updated, or removed; will be a

nullor empty if the event was triggered by theclear()method - oldValue Gets the initial value if the entry was updated or removed; will be a

nullor empty if a new item was added or theclear()method was invoked - newValue Gets the new value for new and updated entries; will be a

nullor empty if the event was triggered by either theremoveItem()orclear()methods - url Gets the URL of the page on which the storage action was made

- storageArea Gets a reference to either the window’s

localStorageorsessionStorageobject, depending on which was changed

Many browsers initially began supporting storage events without fully implementing the properties of the StorageEvent interface specification, so some older browsers might trigger storage events, but the properties outlined here might be null or empty.

18. Bubbling & canceling events

Unlike some other types of events, the storage event cannot be canceled from within a callback; it’s simply a means for informing subscribers when a change occurs. It also does not bubble up like other events.

19. Subscribing to events

To begin listening for event notifications, add an event handler to the storage event as a follows.

function respondToChange(e) {

console.log(e.newValue);

}

window.addEventListener('storage', respondToChange, false);

To trigger this event, perform an operation like the following in a new tab within the same site.

localStorage.setItem('name', 'James');

Binding to storage events using jQuery

An alternative method to using addEventListener() for your subscriptions is to use the event binding features jQuery provides. You have to update your responsToChange() method because it will now return a different event that actually wraps the raw event you were working with in the previous example.

function respondToChange(e) {

console.log(e.originalEvent.newValue);

}

$(window).on('storage'), respondToChange);

20. Using events with sessionStorage

In the previous lesson, you learned that browser context dictates when data can be shared. Because the context for localStorage includes other tabs and windows, notifications are passed to each open instance. However, sessionStorage gains little benefit from events because its context includes the active tab only. Current browsers have included <iframe> elements within that context definition, so it is possible to pass notifications to and from them if necessary.

21. Lesson summary

- Other tabs and windows can subscribe to storage events to receive notifications when a change occurs to

localStorage - The StorageEvent object passed to subscribers contains detailed information regarding what changes were made.

- Because

sessionStoragedata is not shared beyond the current tab or windows, others will not receive notifications when a change occurs. - Storage events cannot be cnaceled and do not bubble up.

22 Lesson review

- Which of the following is not a property of the StorageEvent object?

- oldValue

- key

- changeType

- storageArea

- If you modify a value stored in

sessionStorage, which of the following could receive notifications of the change (if subscribed)?- Another tab opened to a page on the same domain

- A second browser window open to the same page

- An iframe on the same page whose source is within the same domain

- The operating system that is hosting the browser

- Which of the following is the correct way to cancel a storage event?

- event.returnValue = false;

- event.preventDefault();

- event.stopPropagation();

- Storage events cannot be canceled after they are triggered.